MH17: Flying Over A Conflict Region Is A Common Practice For Commercial Airlines

It sounds improbable: A commercial jet, loaded with passengers traveling from one international city to another, knowingly travels over a part of the map where armies with high-tech arsenals are actively seeking to destroy one another. Yet that scenario happens every day, as long-haul carriers seeking the shortest point between origin and destination fly over the world's many hot spots.

The fact that Malaysia Airlines flight 17, bound from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur, was brought down by a missile strike in a field in eastern Ukraine amounts to an extraordinary event. The fact that it was there in the first place was standard operating procedure.

In a world in which global airspace is connected by more than 58,000 flight routes, commercial airliners travel through conflict regions every day, bringing people whose lives are confined to the relative peace of London, New York, Frankfurt and Tokyo directly over Libya, Afghanistan, Sudan and Ukraine.

“Flights over troubled regions are very common,” said Dave Powell, dean of Western Michigan University’s College of Aviation and a retired Boeing 777 captain at United Airlines. “Both governments and airlines take a look at the threats out there, of course. But when you’re trying to save money and competing against everyone else, my guess is, everybody is doing that kind of routing.”

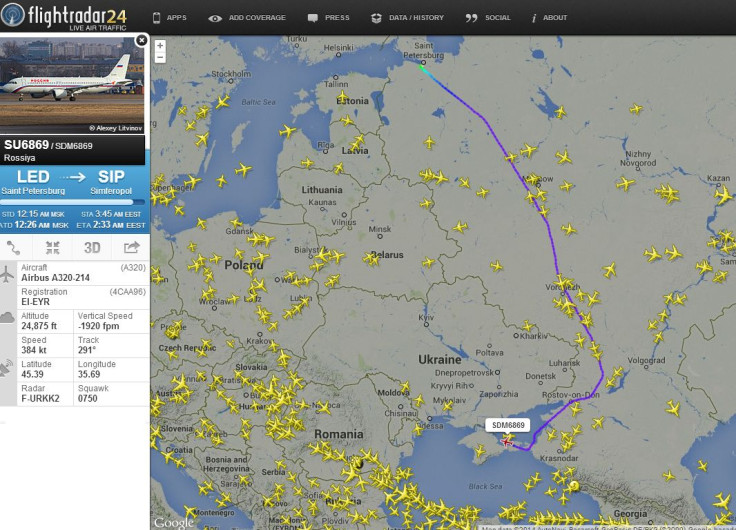

Indeed, a search of flights on real-time airline tracking website Flightradar24.com shows dozens of airliners flying through conflicted areas in the Middle East, South Asia and Africa. At least two other commercial airliners were near MH17 when it crashed. Information on flightradar24.com showed that Singapore Airlines SQ351 (a Boeing 777) and Air India AI113 (a Boeing 787) were within about 15 miles of the #Malaysia Air flight when it lost contact with traffic controllers.

In some cases, national aviation authorities do ban their carriers from flying through certain regions. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administratin issued a “Notice to Airmen,” or NOTAM, in April prohibiting U.S. pilots and airlines from flying in the Crimea region of Ukraine due to disputes over who controlled air traffic in the area. But the site of Thursday’s crash was about 200 miles from that region.

The FAA issued an order on Thursday night prohibiting American aircraft from flying over eastern Ukraine following the downing of a Malaysia Airlines flight in that region. Late Thursday, the FAA expanded the restricted area to include the entire Simferopol and Dnepropetrovsk flight information regions.

Many aviation authorities take their cues from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the U.N.’s agency responsible for making recommendations for the safety of air transport. “Based on guidance from ICAO, a lot of regulators restricted flights around Crimea,” said Sean Cassidy, vice president of the Airline Pilots Association. “But at the end of the day, it’s up to individual countries to impose their rules.”

Airline industry analyst Robert Mann said that even if a civil aviation authority does not impose restrictions on a region, individual operators can and do sometimes choose not to fly through certain regions. “There’s no prohibition on using common sense,” he said. “Any individual operator, whether it’s a pilot or company dispatch, can exercise caution and not fly in an area they deem to be risky.”

When Mann was an executive at Tower Air in the 1990s, the airline refused to route its flights from Amsterdam to the Indian subcontinent via Iran. “The direct routing would have gone over Iran, but we took the fuel and operating cost penalties,” he said. After Thursday's crash, many carriers restricted flights over the airspace where MH17 was downed.

Last year, conflict in Syria prompted regional airlines including Qatar Airways and Saudi Airlines to reroute certain flights to avoid Syrian airspace. Lebanon’s Middle East Airlines, however, kept its routes over Syria.

“All airlines perform a risk assessment,” Powell said. “In the case of MH17, the air traffic controllers routing them that way probably didn’t think there was any threat. I’m sure this incident will now prompt commercial airlines to look at routes differently. Twenty-twenty hindsight is very clear.”

Not all airlines exercise the same level of caution. An anonymous pilot of a “major European airline” told the Guardian, “We would often avoid areas where there is air-to-air conflict, but we flew over Iraq and Afghanistan when the British and U.S. armed forces were deployed there, because only one side was using military jets. There will be weapons based on the ground when you are at 30,000 feet, but that is far up in the air. There are not many missile systems that can be so accurate.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.