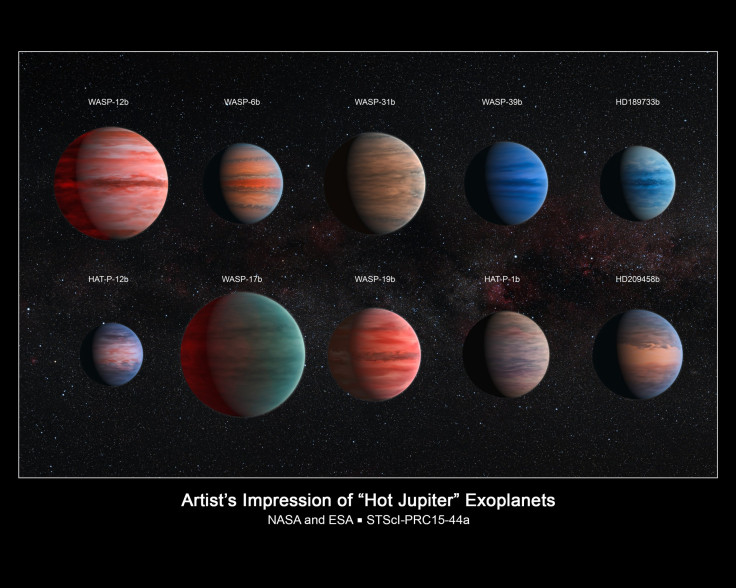

Missing Water On 'Hot Jupiter' Exoplanets Hiding Under Hazy Skies, New Study Finds

“Hot Jupiters” -- large, massive exoplanets locked in an extremely close orbit around their parent star -- have long puzzled scientists. One mystery relates to water, or lack thereof, on the surface of these exotic giants. Even accounting for the proximity to their parent star, which makes these planets extremely difficult to study, many hot Jupiters appear to have less water than expected.

Now, a team of scientists who observed the planets using the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes think they may have solved the mystery. They found that while some of these planets had clouds, others did not, and that those with clouds showed a much wider difference in size when observed under visible and infrared wavelengths. This observation led them to conclude that clouds, along with haze, were most likely masking the chemical fingerprints of surface water.

“Our results suggest it’s simply clouds hiding the water from prying eyes, and therefore rule out dry hot Jupiters,” Jonathan Fortney, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at University of California in Santa Cruz, and coauthor of a study published in the journal Nature, said, in a statement released Monday.

Our current understanding suggests that since hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, and oxygen is the third most abundant, gas giants -- formed out of a disc of debris around a newborn star -- should have plenty of water within them.

“The alternative theory to this is that planets form in an environment deprived of water, but this would require us to completely rethink our current theories of how planets are born,” Fortney said, in the statement.

However, unlike Earth, where clouds are made of water vapors, clouds on these scorching planets most likely consist of something more exotic -- liquid iron droplets.

“We found the planetary atmospheres to be much more diverse than we expected,” lead author David Sing from the University of Exeter, U.K., said, in the statement. “I am really excited to finally see this wide group of planets together, as this is the first time we’ve had sufficient wavelength coverage to compare multiple features from one planet to another.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.