NASA Reveals New Details About Ozone Hole, Says No Signs Of Recovery Yet

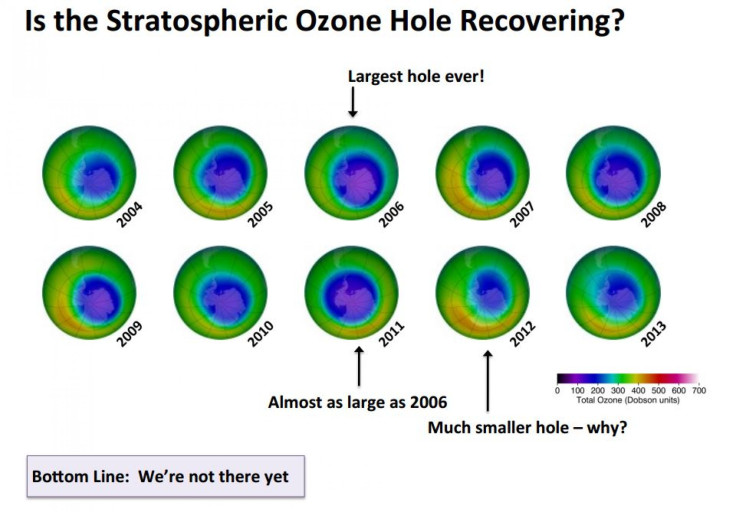

Revealing new details about the inner workings of the ozone hole, the annual thinning of the protective ozone layer in Earth’s stratosphere over Antarctica, scientists at NASA said on Wednesday that the declining amount of chlorine in the stratosphere has not yet caused a recovery of the seasonal depletion of ozone in the region.

It has been more than 20 years since the Montreal Protocol agreement limited human emissions of ozone-depleting substances. And, although satellites have monitored the area of the annual ozone hole and watched it stabilizing and ceasing to grow larger, two new studies have shown that conclusive signs of recovery of the ozone hole have not yet been found.

“Ozone holes with smaller areas and a larger total amount of ozone are not necessarily evidence of recovery attributable to the expected chlorine decline,” Susan Strahan of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said in a statement. “That assumption is like trying to understand what's wrong with your car's engine without lifting the hood.”

Strahan and Natalya Kramarova of NASA Goddard used satellite data to examine the 2012 ozone hole, the second-smallest hole since the mid 1980s, to find out what caused the hole’s diminutive area. The scientists eventually converted the data into a map, which revealed that the 2012 ozone hole was more complex than previously thought.

According to NASA, the classic metrics suggest that the ozone hole has improved as a result of the Montreal Protocol but in reality, weather was responsible for the increased ozone and the resulting smaller hole, as ozone-depleting substances in 2012 were still elevated.

Another research led by Strahan tackled the ozone holes of 2006 and 2011 -- two of the largest and deepest holes in the past decade -- and showed that they became that way for very different reasons.

Strahan used satellite data to track the amount of nitrous oxide, a tracer gas related to the amount of ozone-depleting chlorine. The researchers were surprised to find that the holes of 2006 and 2011 contained different amounts of ozone-depleting chlorine -- a finding that led them to question how the two holes could be equally severe.

Further analysis revealed that in 2011, there was less ozone destruction than in 2006 because the winds transported less ozone to the Antarctic. This was a meteorological effect and not a chemical one. In contrast, winds blew more ozone to the Antarctic in 2006, which led to greater destruction of the ozone.

According to NASA, the second study shows that the severity of the ozone hole, as measured by classic measurements, does not reveal the significant annual variations in the two factors that control ozone -- the winds that bring ozone to the Antarctic and the effect of chlorine on the ozone hole.

Scientists said that chlorine levels in the lower stratosphere are expected to decline below early 1990s levels only by 2030, and will thus become the primary factor in determining the size of the ozone hole.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.