National Park Service Maps Noise Pollution While Studying Effects On Visitors, Wildlife

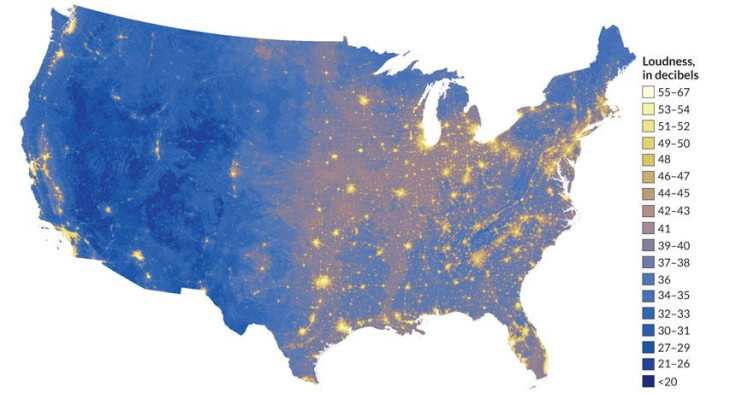

The National Park Service is on a mission to determine the quietest and noisiest places within the boundaries of the U.S. national park system, and it has expanded its data to create a map of the noisiness of the entire country. Scientists estimate that humans cause extra noise in more than 88 percent of the contiguous U.S., compared with the sounds that would naturally occur. The National Park Service has been charged with preserving the serenity of its properties since the Organic Act declared such peacefulness to be a public resource that should be protected along with the vistas and wildlife of the nation’s most treasured lands.

That order has only gotten more difficult for the park service to uphold over the years. "Both noise and light pollution are growing far faster than population in the U.S.,” Kurt Fristrup, a scientist with the National Park Service’s division of natural sounds and night skies, said during a press briefing at the annual conference of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in San Jose, California, on Monday.

Noise in national parks (as well as other places) can harm wildlife and cause changes in the behavior of an individual animal or the reproductive success of an entire community. Songbirds have been shown to alter the timing of their songs in cities, for example, to later at night after the din has died down. About a third of bird species will disappear altogether from areas that are excessively loud, Clinton Francis, a biologist at California Polytechnic State University, said during a briefing about a new study published Monday in "Global Change Biology" regarding how birds respond to noise. And noise pollution can have a meaningful impact on human visitors, too, since an overwhelming number of them (91 percent) go to the parks to listen to natural sounds inherent to a place.

Fristrup and his colleagues have been studying human-caused noise in the nation’s parks for a decade or more in some places. Most recently, his team placed 600 sound monitors in parks around the country (from Denali National Park and Preserve in Alaska to Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming) to gauge how much noise pollution was infringing on these lands. Then, they built the above map of noises throughout the continental U.S. by extrapolating their findings from the study of national parks -- for reference, a normal conversation registers at 60 decibels.

By his measurements, a visitor who is standing within a national park on any given day will hear human-caused noise about 25 percent of time. Much of that noise is caused by airplanes flying overhead, a problem that Fristrup said is just as intrusive across the 6 million acres of remote land in Denali as in the most congested of parks. "I was surprised by the ubiquity of aircraft noise across all parks," he said. In Yellowstone National Park, the sound of airplanes overhead can raise the volume in the backcountry by 5 decibels compared with natural levels.

The National Park Service has worked to minimize such disturbances whenever possible. In some cases, Fristrup said park officials have had to think creatively -- for example, offering incentives that allow bus operators in Yellowstone to bring in more people if they drive quieter vehicles, and reworking tour schedules so that these buses arrive in groups rather than a steady stream. Installing a simple sign asking people to be quiet has cut human-caused noise so significantly at Golden Gate National Recreation Area in San Francisco, California, that noisiness there is now equivalent to levels that would be expected with half as many visitors, Fristrup said.

Other policies have aimed to minimize conflicts between users who would prefer to ride in on their noisy all-terrain vehicles or snowmobiles and those who would prefer a quiet hike. Park officials once recorded as many as 1,500 snowmobiles a day in Yellowstone National Park, but today, they enforce a limit of 318 per day.

Fristrup said one of the main challenges in moving any such efforts forward is that as noise pollution increases, the public's standards for quietness may erode. “People just won’t realize that it could be that much quieter,” he said. He’s concerned that the steady noise of today’s cities and the popularity of iPods are creating a “learned deafness” in which people are conditioned to tune out the sounds around them. “What I really worry about is when that generation of visitors comes to national parks -- they just may not be able to reach out with their ears and experience everything there is in that park,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.