In Sweden, A Patriarchal 'Remnant' Jars With Image Of Equality

A member of the Swedish nobility, Carl Johan Cronstedt, 75, is the tenth generation to have inherited the family estate and home.

Built in 1656 and designed by French-born architect Jean de la Vallee, Fullero castle and its 700-hectare (1,729-acre) estate has been handed down from father to son since 1739, when Cronstedt's ancestor made it a "fideicommissum".

Under this centuries-old provision in Sweden's inheritance law, a noble family's property is bequeathed to a single heir -- in practice, usually a son -- to the detriment of other siblings.

The aim is to keep the estate intact and although slowly dying out, it is still in use in Sweden today, provoking surprise and controversy in a country that champions gender equality.

Imported from Germany, Swedish nobility adopted the practice in the 17th century.

It required families to stipulate the criteria for becoming the heir -- commonly at that time, it was the first-born son -- which was then to be respected by all the generations to come.

"It was a way for the rich to maintain their strong position in society," Martin Dackling, a historian at Lund University, told AFP.

While, in theory, an eldest daughter could be named the beneficiary in a will, in the vast majority of cases properties are passed to the son, he said.

"Sweden is one of the last countries that still has this," Dackling added.

"It's an almost feudal remnant and it's somewhat remarkable that it can remain in Sweden where you normally don't have these types of differences left," he added.

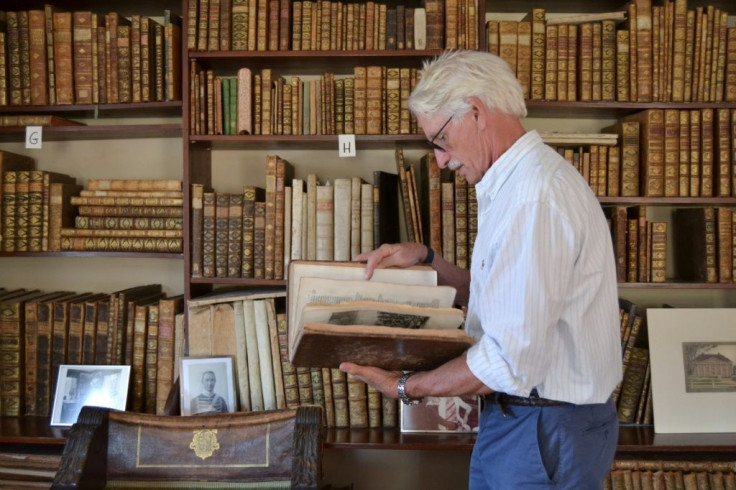

Well-dressed and jovial, Carl Johan Cronstedt takes pleasure in regaling its history as he welcomes visitors to Fullero, a charming, wooden building, located about 10 kilometres (six miles) from the eastern city of Vasteras.

In the castle's left wing, he proudly shows a letter written by 18th-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau to one of his ancestors.

"I am the tenth generation at Fullero. I have a son, a daughter and five grandchildren," the count says, turning to his 45-year-old son and oldest child, also named Carl.

"If the fideicommissum is extended it is my son who will inherit Fullero after my passing," Cronstedt says, adding his wish is for the estate to remain in the family.

In 1963, acknowledging that the form of inheritance was falling into obsolescence, Sweden's social-democratic government passed a law to dismantle the few hundred remaining fideicommissums.

However, it retained the possibility that a fideicommissum could be extended by the government if petitioned by a family.

Nearly 50 years later, 10 fideicommissums remained and the dismantling has dragged on due to several extensions granted in the 1990s.

"If the historical and cultural value of the property cannot be preserved from one generation to the next, the government can grant an extension of the fideicommissum, but only for one generation at a time," Dackling said.

In 1995, Fullero was granted its first extension, after the family argued that the estate would become fragmented if passed on to several heirs, thereby risking its historical value.

Following that decision, several fideicommissums used the same argument to keep their estates intact.

Cronstedt now wants the exception to be extended indefinitely, a request which sparked controversy after it was reported in the Swedish media earlier this year.

Former government minister Annika Strandhall told the Dagens Nyheter daily that the system had no place in modern society.

"There should reasonably be other ways to preserve the historic, cultural and natural interests (of a site) other than through a fideicommissum," she said.

The count says that if their request were granted, the privilege would no longer be reserved to the family's male heirs.

"In addition to the application for the extension, we have also applied for it to be done gender neutrally, meaning the eldest child will get the fideicommissum, instead of the eldest son," he said.

Walking across a freshly mown lawn on an unusually hot summer day, Carl Cronstedt the younger says he hopes to keep the estate, as his father did, so that he can take care of "an old farm that has a lot of cultural and historical value".

If his family's request is denied, the law set up to dismantle fideicommissums remains favourable to him, as half of the estate will go to him, while the other half would be divided between him and his sister.

His sister, also concerned about preserving the estate, supports the family's case presented to the government.

Beyond sibling injustice, journalist Bjorn af Kleen, who wrote "Jorden de arvde" ("The Land They Inherited"), argues that the survival of the fideicommissum has allowed Swedish aristocrats to keep their properties -- often valued at several million euros -- through the centuries.

In regions such as Scania and Sodermanland, 13 percent of the land still belongs to noble families, even though they make up only 0.25 percent of the population, Kleen says.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.