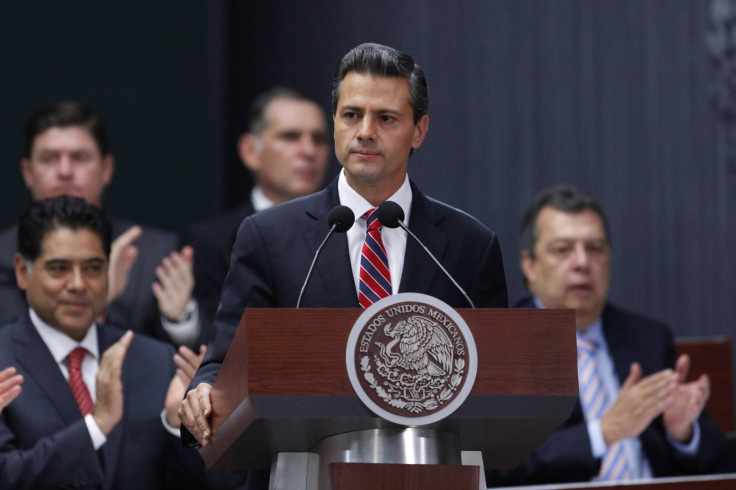

Taxman Cometh: Mexican President Pena Nieto Proposes Diluted Fiscal Reform Package

In the midst of protests over the still unresolved overhaul of the country’s key energy sector, Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto presented his much anticipated fiscal reform program -- which turned out to be much more modest than opposition figures had feared. For example, the proposed reforms do not impose, as had been previously hinted, any taxes on basic goods or medicines, a move the president justified by citing the current weak state of Mexico’s economy. “The economy is growing slower than we hoped, and therefore, a tax on basic goods would be counterproductive to the well being of the citizens,” Peña Nieto said.

Another major feature in the reform scheme concerns a reduced tax on the huge state-controlled oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), which is deeply in debt and undergoing its own reforms, as noted by Spanish newspaper El País. PEMEX will see its fiscal obligations reduced from a 79 percent tax on revenue to 60 percent. Other measures in the package include an increase in the top personal income tax from 30 to 32 percent for those who make at least 500,000 pesos (around $38,000) annually, as well as a 10 percent capital gains tax. The reforms also establish a tax on gas consumption, proceeds of which will go to environmental remediation issues, and another tax on the consumption of sugary soft drinks, which will be used to fight obesity (among OECD states, Mexico has the second worst problem with obesity, after only the United States).

Peña Nieto called the fiscal reform package a “social change,” that will allow for the creation of universal health care and unemployment insurance. He also said that revenues generated from higher personal income taxes will be applied to fund improvements in education and infrastructure and also promote growth of the economy. The president assured that his proposed changes will bring up the GDP by 1.4 percent in 2014 and by 3 percent by 2018, reported Mexico City newspaper El Universal.

David Rees, an emerging markets economist at Capitol Economics in London, mildly cheered Nieto’s watered-down reform program, but warned it does not go far enough. Calling the reforms the “most significant in recent [Mexican] history,” Rees cautioned that they will still leave the government highly reliant on oil as a source of revenue. “The reforms are an attempt to address long-standing vulnerabilities in … Mexican public finances,” Rees wrote. “The crux of the issue is that the government’s tax income is too small.”

Indeed, according to OECD data, the overall public sector tax revenues generated in Mexico amounted to only 18.8 percent of GDP as of 2010, versus 32 percent in Brazil and 35 percent for the OECD as a whole. “What’s more, around one-third of government revenues come from the state-owned oil company, PEMEX,” Reed added. “Admittedly, Mexico is less dependent on commodity revenues than other parts of Latin America. In Chile, for example, copper is responsible for around half of public sector tax receipts. But the key point is that the health of the public finances [in Mexico] has become increasingly dependent on oil prices remaining high.”

Rees contends that Nieto's reforms will help to boost revenues and broaden the tax base -- but only up to a point. “The [Mexican] government only expects additional tax receipts to be the equivalent [of] around 3 percent of GDP,” he said. “The limited scale of the reforms is a reason why, having previously targeted a balanced budget this year, the authorities are seeking permission to run a budget deficit equivalent to 0.4 percent of GDP this year and a further 1.5 percent of GDP in 2014.”

While conceding that Mexico is not at any immediate risk of slipping into a financial crisis, Rees warned that such a modest reform package means the government remains too heavily dependent on the oil economy. “That, in turn, also calls into the question the viability of the large and ambitious investment plan (worth 25 percent of annual GDP over the next six years) that was announced earlier this year,” he added. “Financing the investment project will require oil prices to remain high along with some additional borrowing.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.