Charlie Hebdo Attack: Why Muhammad Cartoons Sparked Outrage Among Muslim Attackers

Witnesses to Wednesday’s attack at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo said the shooters claimed to have acted out of reverence for Muhammad, whose image has appeared in several of the paper’s cartoons mocking the Islamic prophet. The gunmen, who may have had ties to Al Qaeda, said the attack “avenged” the prophet for the paper’s lampooning.

Depicting the prophet in images and illustrations is not -- in itself -- traditionally held to be blasphemous in Islam, according to religion experts. “There’s no blanket prohibition that you can point to from classical times,” David Cook, professor of Islamic studies at Rice University in Texas, told International Business Times. In fact, the Quran makes no mention of banning images of Muhammad, and his visage continues to appear in books and on figurines. “There are still sections of the Muslim world where you can buy these things,” Cook said. “I picked up a Muhammad keychain in Malaysia,” a country whose population is majority Muslim.

Portrayals of Muhammad have appeared in Islamic texts throughout Muslim history, especially in pre-modern texts from between the 14th and 19th centuries, according to scholars. But unlike the Charlie Hebdo caricatures, those historical depictions portrayed the prophet in a reverential light, including his ascension into heaven. “Now you have a whole series of people taking Muhammad and portraying him in ways that are very offensive or semi-offensive,” Cook said.

It is not just the fact that the Charlie Hebdo cartoons were of Muhammad that angered some followers of Islam, rather “it’s the fact that the discourse is out of the control of Muslims,” Cook said.

The text most commonly cited by Muslims who believe Muhammad should not be portrayed is from the hadith, a collection of the oral teachings attributed to the prophet. In it, he instructs his followers not to make him into a symbol or emblem. The hadith were compiled long after Muhammad’s death in 632 A.D.

The images that reportedly most enraged the Charlie Hebdo attackers included a recent cartoon showing Muhammad being beheaded by a member of the Islamic State group under a French caption reading, “If Muhammad were to come back.” Another cover of Charlie Hebdo depicted an Orthodox Jew pushing a Muslim man seated in wheelchair. The caption read, “Intouchables 2,” a reference to a French film about an aristocratic quadriplegic who is assisted by a poor black man.

Another cartoon showed a barrage of bullets striking Muhammad, who is holding a copy of the Quran. The caption reads, “Quran is crap, it doesn't stop bullets.”

“That disrespect is connected with memories of Western notions of cultural superiority and imperialism when Muslims were seen as inferior to Westerners,” Ali Asani, professor of Indo-Muslim and Islamic religion and cultures at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, told IBTimes. Muslims are most inclined to be offended by works that specifically target Islam or the prophet, he said.

In 2005, Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a dozen cartoons poking fun at Muhammad. The incident quickly sparked controversy among Muslims across the world. Hundreds of people were wounded or killed during protests against the cartoons. Nevertheless, some newspapers in Muslim countries republished the cartoons in reporting on the affair. “There's no doubt that these cartoons have been very provocative and Muslims have felt very insulted by them, and the vast majority of Muslims don't see this as an issue of free speech the way the West has been posing it,” Pakistani journalist and religious scholar Ahmed Rashid said during an interview on NPR in 2006, five months after the original publication of the Danish cartoons.

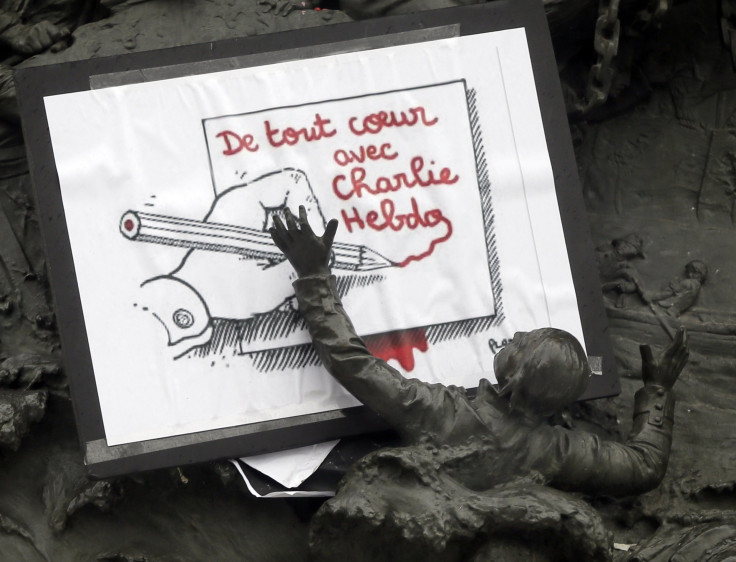

On Wednesday, 12 people were killed at the Charlie Hebdo headquarters in Paris, including the magazine’s editor and foremost cartoonist, Stéphane Charbonnier. The shooters are believed to be 32-year-old Said Kouachi, his brother, 34-year-old Cherif Kouachi, and 18-year-old Hamyd Mourad. Mourad turned himself into the authorities late Wednesday. Investigators are still on the hunt for the two other assailants.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.