Venus Exploration: Venera-D Scientific Missions Discussed By Russia, US Scientists

At a three-day meeting in Moscow, from March 14-16, scientists from Russia and the United States discussed the scientific objectives of the next planned mission to Venus, Venera-D. Planned for a launch in 2026-2027, the Russian mission continues the Venera spacecraft series of the erstwhile Soviet Union, and the D in its name stands for dolgozhivuschaya, Russian for long-lived.

The Russia-U.S. Joint Science Definition Team (JSDT) discussed the architecture, possible scenarios and the scientific payload of the mission, according to an emailed statement by the Space Research Institute (IKI) of the Russian Academy of Sciences, where the meeting took place.

According to the statement, the meeting ended with the following conclusions: “The nearest task of the JSDT would be more focused analysis of the project and its technical feasibility with regard to modern technologies. Another task is to look more closely at mission’s possible scenarios assuming launch in 2026-27. Then, the scientists will search for potential landing site candidates, which would meet both scientific and engineering requirements.”

Read: Russia, US Cooperating On Next Venus Mission

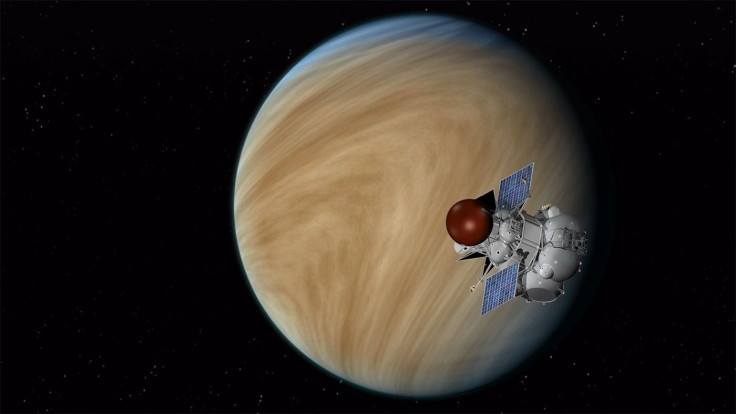

Ahead of the meeting, the JSDT submitted a report to the participating institutions in January, outlining some of the possible scenarios for Venera-D. As of current planning, the mission will have an orbiter and a lander, with the former operating for up to three years above the Venutian atmosphere and the latter to be designed to survive on the planet’s surface for a few hours. There could also be a solar-powered airship that will explore Venus’ upper atmosphere independently for up to three months.

Despite being the closest planet to Earth, not just in terms of distance, but also composition and size, Venus is still quite a mystery to us. Its extremely harsh environment makes it a very difficult place to study, as clouds of sulfuric acid in its atmosphere and near-surface temperatures of about 470 degrees Celsius (880 degrees Fahrenheit) make it difficult for any Earth instruments to survive there.

Since the first Venera mission (Venera is the Russian name for Venus) in 1961, only a total of 10 probes have successfully landed on the planet, all of them Russian. The JSDT working on Venera-D is made up of scientists from IKI, NASA and other Russian and U.S. organizations, and is co-chaired by Ludmila Zasova of IKI and David Senske of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Ahead of the meeting, in a statement on March 10, Senske said: “On a solar-system scale, Earth and Venus are very close together and of similar size and makeup. Among the goals that we would like to see if we can accomplish with such a potential partnership is to understand how Venus’ climate operates so as to understand the mechanism that has given rise to the rampant greenhouse effect we see today.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.