520-Million-Year-Old Arthropod Fossil Reveals Earliest Known Central Nervous System [PHOTOS]

The earliest known central nervous system has been found in fossilized remains of a 520-million-year-old creature.

The extinct animal, a marine arthropod known as megacheiran, was unearthed at the Chengjiang fossil site in southwest China. Its inch-long body was examined by a team of American and British researchers that subjected the fossil to a set of scans that uncovered a complete central nervous system. The findings were published in the current issue of the journal Nature.

"We now know that the megacheirans had central nervous systems very similar to today's horseshoe crabs and scorpions," senior author of the study, Nicholas Strausfeld from the University of Arizona, said in a statement.

The creature, which belongs to the extinct genus Alalcomenaeus, has an elongated, segmented body with dozens of pairs of appendages that allowed the animal to swim or crawl. Like scorpions, they had scissor-law claws that allowed the animals to grasp and sense their surroundings.

"Our new find is exciting because it shows that mandibulates (to which crustaceans belong) and chelicerates were already present as two distinct evolutionary trajectories 520 million years ago, which means their common ancestor must have existed much deeper in time," Strausfeld said.

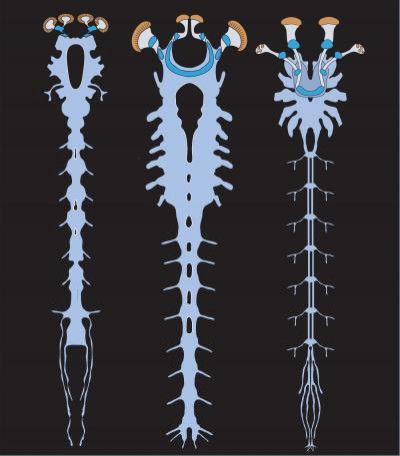

Researchers used CT scans and other imaging techniques to outline the nervous system of the ancient animal. However, "the CT scan didn't show the outline of the nervous systems unambiguously enough," Strausfeld said. The team then used advanced imaging techniques and overlaid the results on top of those from the CT to show the preserved central nervous system.

"We have now managed to add direct evidence from which segment the brain sends nerves into the great appendage,” coauthor Greg Edgecombe from London’s Natural History Museum said. “For the first time we can analyze how the segments of these fossil arthropods line up with each other the same way as we do with living species – using their nervous systems."

Much like a scorpions and spiders, the 520-million-year-old fossil shows a central nervous system with three clusters of nerve cells, also known as ganglia, fused together and the brain connected to some of the animal’s body ganglia.

The novel discovery also allowed researchers to place the previously undescribed creature in the evolutionary chain. "Greg plugged these characteristics into a computer-based cladistic analysis to ask, 'where does this fossil appear in a relational tree?'" Strausfeld said. "Our fossil of Alalcomenaeus came out with the modern chelicerates."

The creature’s spider-like brain, led researchers to realize that chelicerates -- spiders, scorpions and their relatives -- branched off from the family tree of other arthropods more than half a billion years ago.

"The prominent appendages that gave the megacheirans their name were clearly used for grasping and holding and probably for sensory inputs,” Strausfeld said. “The parts of the brain that provide the wiring for where these large appendages arise are very large in this fossil. Based on their location, we can now say that the biting mouthparts in spiders and their relatives evolved from these appendages."

This isn’t the first time Strausfeld found answers in arthropod fossils. Last year his team uncovered a 520-million-year-old fossil that showed a complex brain in a three-inch long arthropod.

“It is remarkable how constant the ground pattern of the nervous system has remained for probably more than 550 million years,” Strausfeld said at the time. “The basic organization of the computational circuitry that deals, say, with smelling, appears to be the same as the one that deals with vision, or mechanical sensation.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.