After Charlie Hebdo Attack, Being Muslim In France May Have Become Much Harder

After the Paris attack on the offices of the Charlie Hebdo satirical weekly that killed 12, and is now virtually certain to be the work of Muslim terrorists, France’s 5 million Muslims may find themselves even more isolated and feared by their fellow citizens.

Muslim organizations in France have rushed to condemn the attack on the magazine, which had been firebombed in 2011 after publishing cartoons lampooning Islam. But those condemnations may not help the perception of Muslims in a society where they say they are marginalized.

French Muslims “have for the majority the sensation that they are just second-class citizens,” Dalil Boubakeur, director of the Muslim Institute at the Grand Mosque of Paris, told French site Psychologies before the attack. “Our community feels it’s being regarded severely by people ready to amplify and demonize every detail of its cultural and religious identity,” he said.

French Muslims on social media are already fearing the backlash.

"At this moment there is infinite hatred against Muslims, I don't even want to remain in France," tweeted one user from Paris.

@nakedamethyst en ce moment y a une haine infinie contre les musulmans j'aime même plus rester en France

- ️ (@chersmokes) January 7, 2015“Who is the true loser from all these attacks? Us, French Muslims. We are stygmatized, people fear us for no reason,” wrote another.

Qui sont les vrai perdant de tous ces attentats ? Nous les musulmans de France on est stigmatiser les gens nous craignent pour rien

— Kaboom (@Sofianlonzo71) January 7, 2015

Their fears may be justified, but also overblown, according to one expert.

“For the most part I do not see an immediate backlash,” said Jytte Klausen, a professor at Brandeis University who has written on domestic terrorism and the intersection of politics and religion in Western Europe. “Security forces know that these attacks are often the work of converts. We may well be looking for blonde killers,” she added in a phone interview.

But France is also a nation where mainstream discourse in the media has taken an Islamophobic tone that, in the U.S., would be reserved for the extreme reaches of the right wing.

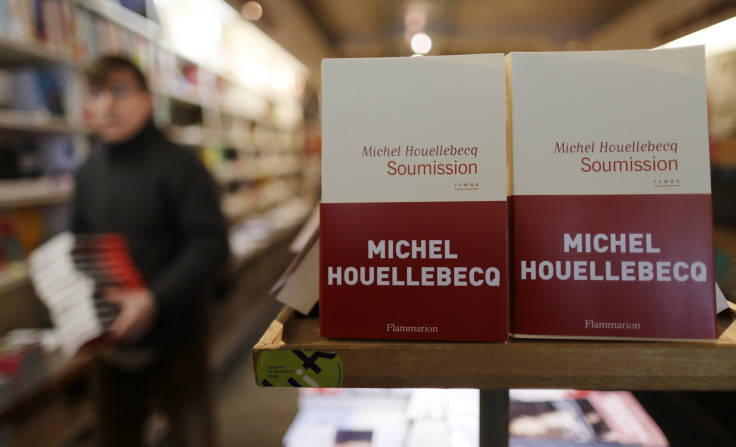

It’s where writer Eric Zemmour has become a popular commentator and sold almost a half-million copies this year of "French Suicide," in which he decries the decline of a nation where “neighborhoods are completely Muslim.” Another best-selling writer and intellectual provocateur against contemporary France, Michel Houellebecq, called Islam “a sh*tty religion” in one of his popular novels.

And it’s most importantly a nation where a far-right party with an anti-immigration and anti-Muslim agenda, the National Front, has been a top contender in national politics for more than a decade, even sending a candidate to a presidential runoff against incumbent Jacques Chirac in 2002.

That candidate, Jean Marie Le Pen, is the kind of politician who says things like "Muslims are two generations late" in cultural and social development. His daughter Marine, now the party’s leader, is making an effort to appear more mainstream, but still makes highly controversial statements, saying for example that Muslims who openly pray in the streets of France “behave like occupants.”

“I’m sure the National Front will do its best to capitalize” on the attack, Klausen said.

There is, after all, a widespread perception that France is being overrun by Muslims. As a matter of fact, less than 8 percent of French residents identify as Muslim, according to a Pew Research poll conducted in 2010 -- but people think almost a third of the country is Muslim. That gap among reality and perception of the presence of Muslims is the biggest in Europe. Only Belgium gets close.

Religious identity in France (2010) Christian 63% Unaffiliated 28% Muslim 7.5% http://t.co/JpUGboVrm2 @vishalnk4 @PritishNandy

- Conrad Hackett (@conradhackett) January 7, 2015Muslims in France Actual 8% Average Guess 31% pic.twitter.com/UWQGJEATgl

- ian bremmer (@ianbremmer) January 7, 2015That skewed perception has produced a reactionary view of Muslims. “This situation of a people within a people … will bring us to chaos and civil war,” Zemmour told an Italian newspaper in September. “Millions of people live here in France and do not want to live like the French,” he said. Asked for a clarification, the writer, unafraid of cliché, explained that this means “giving children French names, being monogamous, dressing French, eating French – cheese, for example – joking in cafés, courting girls.”

The idea that Muslims aren’t like other French people may be bolstered by physical segregation. Many of them live in dilapitaded exurban banlieues where unrest often breaks out, bred by high unemployment and poor living conditions.

“It’s an apartheid that does not speak its name,” wrote Noël Mamère, a member of the National Assembly for the leftist Europe Ecologie Les Verts party, before the attacks.

“French Muslims have made tremendous strides in recent years in terms of professionalization,” Brandeis University’s Klausen said, “and many have been left behind in areas where growth is not very strong. But that affects all French, not just Muslims. I do not see a direct link with the attacks, and most French people know.”

Yet, French voters are rewarding politicians who do not hide an anti-Muslim agenda. Marine Le Pen led the National Front to its biggest percentage of votes ever in the 2014 European Parliament election, when one voter in four chose the far-right party.

And the public debate on Islam in the country is not set to veer toward moderation. Houellebecq’s latest novel, "Soumission," (Submission) was published, in a twist of fate, on the same day of the Charlie Hebdo massacre. It depicts a fictional France in 2022 under a Muslim president who proceeds to turn France into a Muslim country -- after defeating none other than Marine Le Pen in a runoff. Houellebecq denied that he has written an Islamophobic book. In the meantime, the novel has already shot to No. 1 on Amazon’s French site.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.