Antarctica’s Larsen C Ice Shelf Crack Will Create One Of The Biggest Icebergs Ever When It Calves

That the polar ice caps are in trouble is a known fact, but given the large number of factors affecting them and our limited understanding of those factors makes it difficult to pinpoint exactly how dire the situation is. To provide additional data to enhance our knowledge, space agencies around the world use satellites to track the ice shelves, especially in Antarctica.

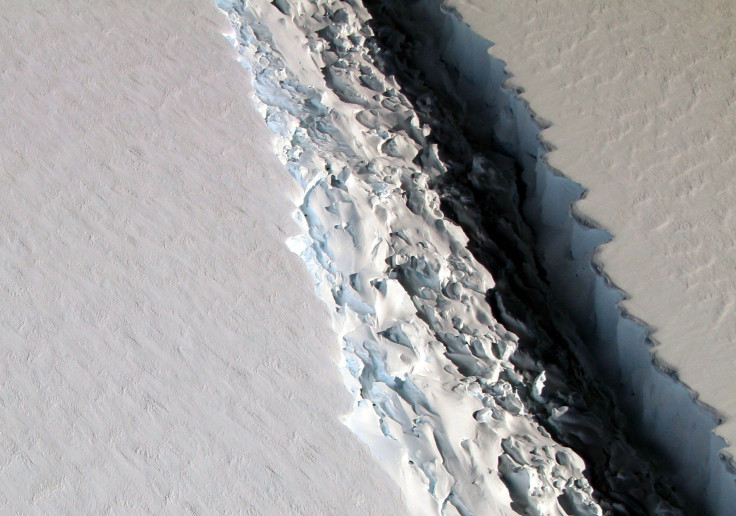

The Larsen C ice shelf — the biggest segment of the Larsen ice shelf in northwest Antarctica — has been a closely watched feature ever since the smaller Larsen B shelf collapsed in 2002. And a large, growing crack in the shelf has scientists worried, since the crack will eventually lead to a huge chunk of the shelf breaking off (an act known as calving) and falling into the Wendell Sea. Satellite images captured by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission was used to create an animation that illustrates the concern.

Read: Antarctica’s Flowing Meltwater Network Is Surprisingly Vast

The radar images from the satellite were not enough to see the entirety of the crack, and scientists used a technique called interferometry, which combines data from two radars to extract information a single radar would not be able to provide. And the ESA scientists found the crack to now be over 175 kilometers (almost 110 miles) long, of which about a third has been added in 2017 alone.

“When the ice shelf calves this iceberg it will be one of the largest ever recorded – but exactly how long this will take is difficult to predict. The sensitivity of ice shelves to climate change has already been observed on the neighbouring Larsen-A and Larsen-B ice shelves, both of which collapsed in 1995 and 2002, respectively,” a statement on the ESA website said.

When large ice shelves break, the icebergs formed as a consequence, in their turn, break into smaller pieces which can pose a navigational risk to marine traffic. But more importantly, these ice shelves act as dams that keep a check on the flow of ice into the sea — a phenomenon, which if left unchecked, would lead to a rise in the sea level. When the Larsen B shelf collapsed, the speed of the Crane Glacier went up threefold.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.