CO2 Emissions Threaten Seafood As Ocean Acidification Spreads Along US Coastlines

Taylor Shellfish Company was grappling with a crisis in the summer of 2009. Millions of oyster larvae were dying in its Washington hatcheries, and production had dropped by 80 percent. Down the coast, Oregon’s hatcheries faced the same problem.

Highly acidic ocean water, it turned out, was dissolving the microscopic oysters. Part of the acid blast came from naturally occurring events. But human-caused "ocean acidification" -- which occurs when oceans absorb carbon dioxide emissions -- was also partly to blame, the company later learned. "There’s no question that [man-made] CO2 contributed to oyster mortality," Bill Dewey, public affairs manager for Taylor Shellfish in Shelton, Washington, said.

The company has since installed high-tech monitoring and water treatment systems in its hatcheries, and oyster larvae have mostly recovered. But seedlings, the next stage in oyster life, are struggling to grow, and the company suspects acidic water could be the culprit, Dewey said.

"We’re the canary in the coal mine for what’s happening with our shellfish industry," he said. "Conditions are going to get progressively worse."

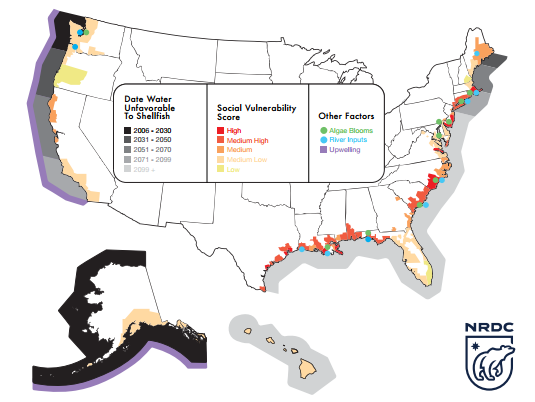

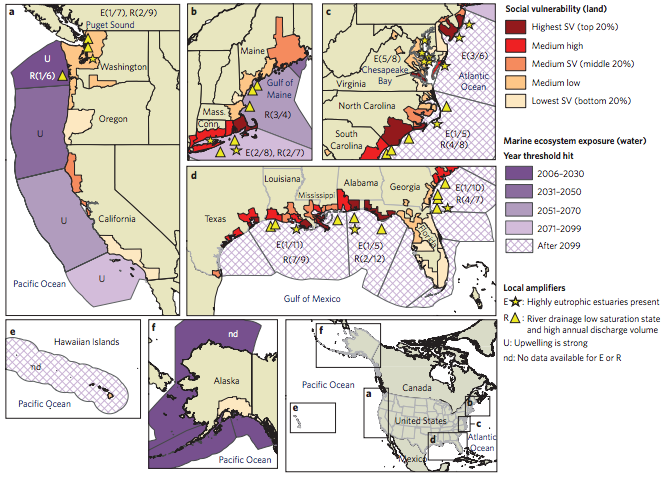

Ocean acidification isn't limited to Washington's waters. The phenomenon is striking more than a dozen other "bioregions" along the U.S. coastline, threatening to disrupt local shellfish industries from southern Massachusetts and Virginia to swampy Louisiana and southern Alaska, according to a new study by the Natural Resources Defense Council. The economic implications could be vast. In the Pacific Northwest alone, acidification already cost the oyster industry an estimated $110 million and jeopardized thousands of jobs, according to a Washington state science panel.

Oceans have so far absorbed about one-fourth to one-third of all man-made carbon emissions, scientists estimate. As the U.S. and other countries burn more oil, coal and natural gas for energy, the ocean could become an increasingly hostile home for marine life.

The NRDC report, published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, is the first to explore how local communities could be harmed by increasingly corrosive waters. Researchers found the threat of ocean acidification to U.S. fisheries is wider than previously understood. "It's hitting a lot more of our coasts than we realized," Lisa Suatoni, a co-author on the report and a senior scientist with NRDC's oceans program, said.

She said the science on ocean acidification is relatively new and researchers worldwide are only beginning to understand its effects on marine life and people. The scientific community established early on that areas with chilly ocean temperatures -- including Alaska, the Pacific Northwest and Maine -- would be particularly susceptible to acidification.

"Cold water absorbs more atmospheric CO2. It's like soda -- if you have a cold soda, it bubbles less," and the gas remains trapped in the liquid, Suatoni explained. "If you have a warm soda, all that CO2 bubbles out."

But the NRDC team found that even bioregions in warmer waters face risks. A variety of local factors such as water pollution, lack of economic diversity and weak political action on environmental issues can all exacerbate problems posed by increasingly acidic waters. "When you look at these additive effects, we suddenly see more regions of the coast will be experiencing rapid ocean acidification," Suatoni said.

For instance, in the Chesapeake Bay on the East Coast, fertilizer pollution from nearby agricultural operations -- which also creates toxic algae blooms -- can accelerate the rate of acidification. Maryland and Virginia's economies have already lost a combined $4 billion in the past three decades as pollution, disease, poaching and habitat destruction clobber clam and oyster farmers, according to a Chesapeake Bay Foundation report.

Coastal Louisiana, another vulnerable region, also suffers from agricultural pollution. But many parishes face additional acidification risks because oyster farming is the only business in town. If the shellfish disappear, so will the jobs. "They don’t have the ability to rebound from harm," Suatoni said of the communities.

Southern Massachusetts is another "hot spot" of vulnerability, since shellfish farmers rely heavily on one species. Nearly three-fourths of local fisheries' revenues come from shelled mollusks, meaning most of the industry's income could vanish if acidification kills the creatures and companies don't diversify, the NRDC report said.

But Massachusetts oysters aren't safe from acidification, either. Seth Garfield, who has raised oysters off Cuttyhunk Island, near Martha's Vineyard, for the past 34 years, said he's worried about his company's future. Cuttyhunk Shellfish Farms buys 1-year-old oyster seeds from nearby hatcheries and grows the bivalves until they're ready to shuck and eat.

"If hatcheries start having problems because of ocean acidification, then grow-out facilities like mine won't be able to get oyster seeds," Garfield said. He'd have to eliminate some part-time jobs and charge higher prices to restaurant buyers, he added.

For now, he's not as concerned that acidification will kill the oysters in his farm, since juveniles are more resilient than younger critters. But if the waters near Cuttyhunk become dramatically more corrosive, the shells of his 400,000-odd oysters could become more brittle and shatter when pried open.

In the past five years, shellfish farmers have increasingly raised the issue of ocean acidification at trade group meetings and aquaculture conferences, Garfield said. State leaders across the Northeast are devoting more attention and resources to studying the risks to local industries and figuring out ways those companies can adapt. Policymakers in Maryland and Maine have each passed measures to create ocean acidification panels and develop state response plans.

Leading the nation in these efforts is the Pacific Northwest, where acidification isn't a near threat but a current problem.

In 2013, the Washington state legislature allotted $1.8 million to create an ocean acidification center at the University of Washington, which monitors ocean chemistry levels, creates short-term forecasts on corrosive conditions and helps develop water treatment methods for area hatcheries. Gov. Jay Inslee's 2015-2017 budget proposal includes an additional $1.6 million for the center. Washington, Oregon, California and British Columbia in Canada recently formed a West Coast science panel to advise policymakers on the causes and consequences of ocean acidification.

Suatori said similar programs and scientific panels are needed across the U.S. to help industries respond to the changing chemistry of the ocean. In many coastal communities, "There's definitely still a lack of awareness" about the threat of acidification, she said. "There's really little time to wait."

On the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico, a direct way to reduce acidification is to eliminate water pollution from farms and industrial plants. Some states have adopted voluntary programs to encourage farmers to apply fertilizer in ways that reduce farm-run off, but environmental groups say only mandatory pollution limits can make a dramatic difference. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is also proposing to strengthen the Clean Water Act in order to protect more wetlands and waterways from industrial pollution, though the measure is facing stiff resistance from Republican leaders in Congress.

In Maine, where the cold water is already naturally acidic, shellfish farmers could begin studying which strains of oysters, clams and mollusks are more resilient in corrosive waters. "They could start artificial selection programs, the same way agricultural producers do for crops," Suatori said.

Pacific Northwest hatcheries could also install monitoring and treatment systems like the ones in place at Taylor Shellfish Farms. The company invested around $45,000 in sophisticated monitoring equipment to track the water chemistry in the oyster larvae facilities, Dewey said. When the water gets too acidic, a water treatment system automatically injects sodium carbonate to restore the pH balance. The company shares its monitoring data with local ocean scientists to help inform their research.

Yet, those approaches are only responses to the problem. To actually slow or halt ocean acidification, the U.S. and other countries must stop burning fossil fuels and eliminate carbon dioxide emissions, climate scientists say. (Other greenhouse gases, including methane and nitrous oxide, aren't absorbed into the ocean.)

The shellfish conundrum "is to a certain extent the tip of the iceberg," Garfield said. "All of this affects not just shellfish, but will lead to [problems] for shrimp and all the other endangered species, like codfish and blackfish."

President Barack Obama and other world leaders have made encouraging promises to reduce emissions and develop cleaner energy alternatives, such as wind and solar power and low-carbon biofuels. Nearly 200 countries are negotiating a global emissions treaty, which leaders have pledged to sign this December at a United Nations-led climate conference in Paris.

In the meantime, however, global carbon emissions are rapidly rising, and the planet is on track to warm by at least 4 degrees Celsius (7.2 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2100 without aggressive action. Scientists generally agree warming should be kept to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) to avoid the most catastrophic consequences of climate change.

But even if countries do eventually curb their greenhouse gases, the carbon that's already in the atmosphere will continue to end up in the oceans, signaling that ocean acidification will continue to pose a major threat to seafood industries in the coming decades, the NRDC report confirmed.

"Conditions are going to get worse over the next 30 to 50 years before they get better," Dewey said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.