Covid-19 Lockdown Intensifying Brazilian Police’s Brutality Against The Poor And Blacks

KEY POINTS

- Brazilian police killed 177 people during the month of April alone

- Rio police killed 606 people in the first four months of the year

- In 2019 Rio’s police killed 1,546 people during police operations

While much of the world focuses its attention upon the police killing in the U.S. of an unarmed black man named George Floyd, one of the most brutal police forces of all operates thousands of miles away in Brazil.

One week prior to the murder of Floyd in Minneapolis, a 14-year-old black boy named Joao Pedro Matos Pinto was killed during a police raid in Rio de Janeiro. The teenager was shot in the back with an assault rifle.

Pinto was only the latest of thousands of victims of Brazil’s notoriously brutal and violent police in recent years – most of the dead were poor and black.

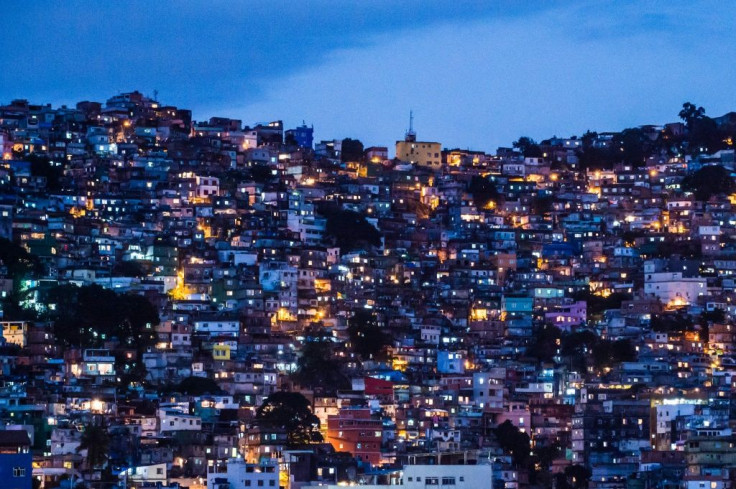

Already a tinderbox of racial tensions and criminal violence, Brazil’s urban centers became even more dangerous when the government ordered a shutdown to curb the spread of covid-19. The clampdown has triggered a new wave of police violence in the poor, overcrowded “favelas” in huge cities like Rio and Sao Paulo.

“In the first 15 days of social isolation there was a sharp drop in the number of [police] operations and armed confrontations in the city of Rio which was really welcomed – because it’s not the time for this,” said Flavia Oliveira, a black journalist and broadcaster.

But by April, bullets were flying again – Brazilian police killed 177 people during the month alone. On May 15, a single police raid ended the lives of 13 people – which some leftist politicians likened to a “massacre.”

“Instead of sending doctors and nurses to protect residents from Covid-19, the government sends police, bullet-proof vehicles and helicopters to kill us,” said Bruno Itan, a photographer. “We are tired. We were afraid of the pandemic, but this is even worse. There were so many bodies it was hard to believe.”

Echoing the widespread protests in the U.S. over the Floyd killing, Brazilians have demonstrated against their own police and security forces – but these protests were much smaller in scope.

“This must stop,” said Pinto’s father. “The police should be protecting us, not killing us.”

Oliveira, the journalist, said: “The favelas are already dealing with a lack of work, income and food,” before the pandemic worsened the suffering.

However, police asserted that Pinto was simply caught in a crossfire as they searched for drug dealers and that casualties are inevitable since criminal gangs are heavily armed.

Others believe the police target young black men indiscriminately.

“Like it or not, there is a racial side to this … and it shouldn’t be like this,” said Pinto’s aunt. “We’re all supposed to be equal … [But] if you’re on the bus and the police get on, they’ll search the people of color first … If a black man runs, he’s guilty. We’re tired of seeing this kind of thing happen.”

Pinto’s father said: “The police need to understand that the favelas are home to good people. Decent black people. But unfortunately when they come into [this] community they treat us all like criminals. They are wrong.”

Human Rights Watch said the Rio police killed 606 people in the first four months of the year. Police accounted for more than one-third of all the killings committed in Rio de Janeiro state in April.

In 2019 Rio’s police killed 1,546 people during police operations – the highest tally since 1998.

If these rates of killings existed in the U.S., police there would kill more than 36,000 people annually (well above the actual figure of 1,000).

Over the past decade, Rio police have killed about 9,000 people – across the country, 33,000 Brazilians have been murdered by police over that time.

“When [Brazilian] President Jair Bolsonaro and Rio de Janeiro Governor Wilson Witzel encourage police to kill even more, as they have done in public remarks, they only empower corrupt, abusive officers, while undermining and endangering officers who abide by the law,” HRW stated. “Rio de Janeiro state authorities need to draft and put into effect a plan with concrete steps and goals to reduce police killings. And when those killings occur, the Rio de Janeiro prosecutor´s office needs to ensure prompt, thorough, and independent investigations, including by opening its own investigations, in addition to those undertaken by the police.”

But the country’s rulers are squarely on the side of the police.

Last Christmas, Bolsonaro pardoned an undisclosed number of police officers who were convicted of criminal violence, including murder.

Bolsonaro, who swept into power in 2018 on a tough anti-crime platform, has even said that police accused of killing "10 or 15" criminals "should be decorated and not have to go to court."

Justice Minister Sergio Moro also proposed a law that would block the prosecution of police accused of crimes in the course of their official duties – the proposal was ultimately rejected by Congress.

Now the Floyd killing has attracted much attention in Brazil.

Thiago Amparo, a lawyer and professor at Fundacao Getulio Vargas Law School in Sao Paulo, commented that Brazil and the U.S. share a “history of deep-rooted racism” – although Brazil has a much higher percentage of black and mixed-race people. Indeed, black and mixed-race Brazilians now comprise a majority of the country’s population, whereas blacks account for about 13% of the U.S.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.