HIV Vaccine: Scientists Find Way To Attack Virus With Your Own Antibodies

One piece of a future vaccine for HIV might be falling into place, as researchers announced they found a way to target molecules that protect the virus from the body’s immune system.

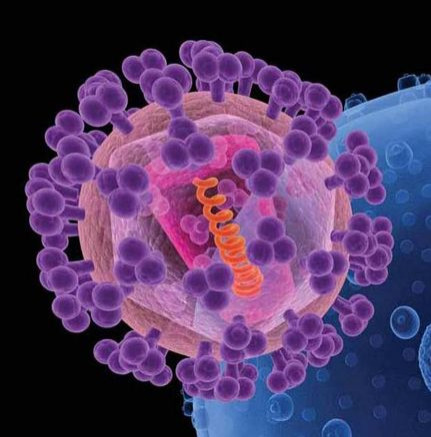

It’s a mixture of protein and sugar that spurs the immune system to create antibodies that fight it off like it does for other foreign invaders, according to the team’s description of its discovery in the journal Cell Chemical Biology. That protein-sugar combo mimics protective layers on the outside of HIV, the virus that leads to AIDS if left untreated, so building antibodies against it could help prevent infection.

That HIV shield covering the virus includes a protein called gp120, which in turn is covered by a layer of sugar. The layers work together as a buffer against the body’s natural defenses.

The vaccine strategy has shown promise in rabbits, with vaccinated animals showing an immune response to a few different HIV strains.

“An obstacle to creating an effective HIV vaccine is the difficulty of getting the immune system to generate antibodies against the sugar shield of multiple HIV strains,” researcher Lai-Xi Wang said in a statement from the University of Maryland. “Our method addresses this problem by designing a vaccine component that mimics a protein-sugar part of this shield.”

Wang called it “an important step in developing immunity against the target and therefore the first step in developing a truly effective vaccine.”

There are rare cases in which people can beat back HIV without medication, the university explained, and those patients often have antibodies that are attacking the problem protein. But because the body contains proteins and sugars that look a lot like HIV’s, many people’s immune systems won’t attack them.

It’s possible the protein-sugar vaccine component will change that.

Another problem is how often HIV strains mutate and how many there are. To get around that, according to the university, the researchers found a piece of the gp120 protein that was common to many different HIV strains and used that to create their vaccine component, along with a sugar molecule that is likewise common to the strains.

Rabbits injected with the protein-sugar combination created antibodies that attached to the gp120 in four prevalent strains of the virus.

Still, the HIV was still able to infect the rabbits’ cells.

According to the university, it could take as long as two years for a person to build up enough immunity to fight off HIV, much longer than the timeframe of this study.

“We have not hit a home run yet,” Wang said. “But the ability of the vaccine candidate to raise substantial antibodies against the sugar shield in only two months is encouraging; other studies took up to four years to achieve similar results. This means that our molecule is a relatively strong inducer of the immune response.”

The researchers are working to improve their method to make the vaccine component more effective.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.