Illinois Budget Crisis: Big Banks Aren’t Sharing State Debt Woes

The state of Illinois has been without an official budget since July, and service providers that rely on state funding have felt the squeeze. Programs that deliver hot food to seniors in southwestern Illinois and outside of Chicago, for example, are preparing to halt operations, and low-income college students have seen promised tuition subsidies vanish.

The western Illinois Child Abuse Council has responded to the frozen state budget by reducing therapy services staffing by 20 percent and home visits by 40 percent. The nonprofit's counseling program, which serves children under 5 years old who have suffered trauma and abuse, has begun turning away families as the waitlist stretches to record length.

“We’re the only ones providing these services in the community,” said Angie Kendall, the organization’s director of development. “We don’t have an alternative at this point.”

Even as crucial social service programs face deep reductions, one set of institutions has enjoyed an uninterrupted flow of funds from Springfield: banks. Financial service providers continue to pull in nearly $70 million a year in payments on complicated public debt deals from the early 2000s.

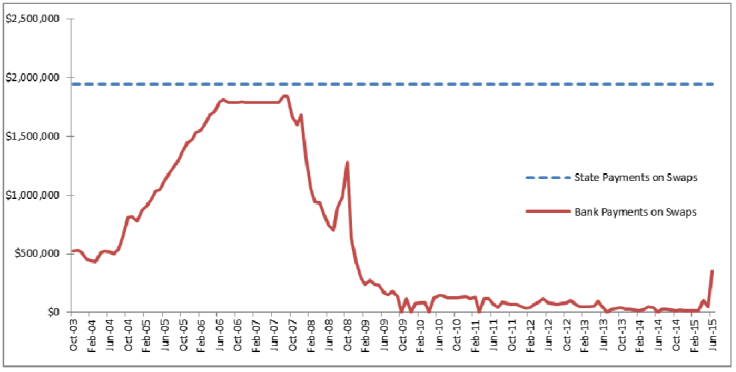

With the state’s financial woes deepening, banks — including JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Citigroup — stand to take in as much as $1.45 billion on interest rate swap payments by 2033. That’s the conclusion of a new report from the ReFund America Project, which tabulated the costs stemming from the swaps weighing on the state’s books.

“These toxic swaps have been an unmitigated disaster for the state, failing in almost every way,” said Saqib Bhatti, a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute and one of the report’s co-authors, in a statement Tuesday. “If state officials knew then what we know now, it would have been financially irresponsible for them to have signed these deals.”

Illinois is just one of many states and municipalities bitten by interest rate swaps gone awry. The list includes the city of Chicago, which has sought to pay around $300 million in penalties to exit its own bad bets after doling out record debt fees in 2015.

“Hindsight is easy,” said Richard Ciccarone, president of Merritt Research Services, which specializes in municipal bonds. “But in this case it just looks like it’s a bad deal. The markets did not work out in their favor.”

Labor leaders, who fear the state’s fiscal difficulties will imperil their members’ pension payouts, have pressed Illinois to make banks share in the fiscal pain, asking Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner to “aggressively pursue” means of recovering swaps fees, arguing that banks made misrepresentations when they sold the swaps.

Gov. Rauner, whose contested budget plan calls for limits to collective bargaining, rejected provisions related to the swaps in contract negotiations. “The union is concerned that the Rauner administration is putting big banks first,” said James Muhammad, a spokesman for Service Employees International Union Healthcare Illinois.

In a statement to the International Business Times, however, the administration did not rule out seeking a way to limit the damage from the swaps. "The Governor’s Office of Management and Budget is doing an in-depth analysis of these swaps in order to reduce the state’s payments and minimize its financial exposure," said Catherine Kelly, Rauner's press secretary.

An interest rate swap is type of financial derivative that allows a bond issuer — like the State of Illinois — to limit or manage exposure to fluctuations in interest rates. The issuer pays a fixed interest rate on a floating-rate bond. The bank on the other side of the swap pays the variable rate and pockets the difference between the fixed and floating rates.

When Illinois first entered into the now-costly swap deals in the early 2000s, the intention was to hedge risks and save money on the billions of dollars in variable-interest bonds that state agencies had issued. These bonds, issued under former Gov. Rod Blagojevich, are pegged to fluctuations in the broader interest rate environment.

But in order to lock in what state financiers saw as bargain interest rates, the governor’s office entered into swap agreements with 10 major Wall Street banks. Under the deals — which are commonplace in the corporate world — the state would pay the banks a fixed interest rate, while the banks paid bondholders the variable rate. In theory, the maneuver would protect the state from sharp interest rate moves.

The arrangement didn’t work that way in practice. When the global financial crisis struck in 2008, the Federal Reserve slashed benchmark interest rates virtually to zero. Unlike mortgage holders other debtors, Illinois wasn’t able to refinance at the lower rates. The swaps kept the state locked into rates nearly 4 percent higher than what its bank partners were paying bondholders.

The state has paid $618 million in swap fees since 2003, according to the ReFund America report, with another $832 million yet to come. While Ciccarone noted that those totals include the interest Illinois would have otherwise paid on the variable-interest bonds, they also include tens of millions of dollars in additional costs related to the complex requirements that swaps entail.

Those fees might not be all. Today, with interest rates still scraping historic lows, termination fees totaling $286 million prevent the state from exiting its swap agreements.

The ongoing budget crisis threatens to force a raft of penalties even sooner. Ratings agencies Moody’s and Fitch both downgraded Illinois state debt in October. If those ratings drop to junk status — as Chicago’s debt did last year — Illinois could suffer automatic terminations written into the agreements. These clauses levy a penalty for exiting the deal early that is based on the present value of future payments on the swaps.

“They’d have to come up with that amount of money right away,” said Ciccarone. “It wouldn’t be an easy thing to do while they’re already so hard-pressed for cash.” For their part, the banks would have the option to forgo termination fees in lieu of renegotiating the agreements.

Labor leaders, however, are hoping for a different type of negotiation, one that might recoup past fees from Wall Street. The campaign comes a month after the Chicago Teachers Pension Fund sued dozens of banks over the doomed interest rate swaps that have added to the city's soaring debts.

Bhatti of the Roosevelt Institute said the lawsuit has a chance, noting that while corporate bond issuers generally take out swaps for a relatively safe period of five to seven years, the state agreements last three decades or more. “We believe the banks that pitched these deals to the state misrepresented the risks,” Bhatti said.

Ciccarone was skeptical that Illinois could prevail in court, given the apparent financial sophistication of state finance officers. As for the banks that profited off of the state’s bad fortune, he said it was luck as much as anything that accounted for the windfalls.

“They made more money than they ever expected,” Ciccarone said. “They were on the right side of the trade.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.