Larry Fink, Other Wall Street Heavies Complain About Short-Termism. Can They Turn The Tide?

A new strain of Wall Street criticism has cropped up in an unlikely place: the C-suite of JPMorgan Chase. There, Chief Executive Jamie Dimon has joined with Laurence Fink, co-founder and head of asset manager BlackRock, to lead regular confabs of industry bigwigs who are concerned that corporate America’s focus on short-term results is getting in the way of long-term growth.

“Today’s culture of quarterly earnings hysteria is totally contrary to the long-term approach we need,” Fink wrote earlier this week in a letter to executives of Standard & Poor’s 500 companies, pushing companies to provide investors with longer-term outlooks rather than quarter-by-quarter snapshots. In recent meetings, he has reportedly shared these ideas with executives at Fidelity, Vanguard, as well as Warren Buffett.

That campaign — which Fink describes as “resistance to the powerful forces of short-termism afflicting corporate behavior” — has brought his critique into the limelight. But some corporate finance experts wonder if Fink’s ethical appeals really address the underlying incentives that drive companies to make unwise financial decisions in pursuit of short-term goals.

“Fink is about halfway there,” said William Lazonick, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Lowell and a leading critic of shareholder value theory, the idea that corporations primarily exist to maximize shareholder returns.

Lazonick contends that simply changing how executives report their goals, as Fink has proposed, can go only so far in reforming a fixation on quarterly profits that has been criticized by everyone from Hillary Clinton to the Oracle of Omaha himself.

“The real distinction is not long-term versus short-term,” Lazonick said, but about differing conceptions of the broader purpose of the stock market. He cites the long-running efforts of activist investor Carl Icahn, who has launched numerous campaigns to wring more dividends and share buybacks out of companies whose shares he owns. Those companies include Apple, which he has badgered for payouts since mid-2013 — not exactly a short-term affair.

Fink and his ilk might decry Icahn’s meddling, but his influence isn’t confined to the quarter at hand. “He has absolutely no relation to the company other than trying to turn his $5 billion into $10 billion,” Lazonick said. In that regard, he’s not too different from institutional investors, many of whom similarly demand that companies focus above all else on returning cash to shareholders.

For Lazonick and Fink, the problem of corporate short-termism is encapsulated in the stock buyback boom. Critics argue that corporate America has overdosed on buying up their own shares, a practice that helps support stock prices, placating investors and executives compensated with stock awards, but comes at the cost of investing in organic growth and the workforce.

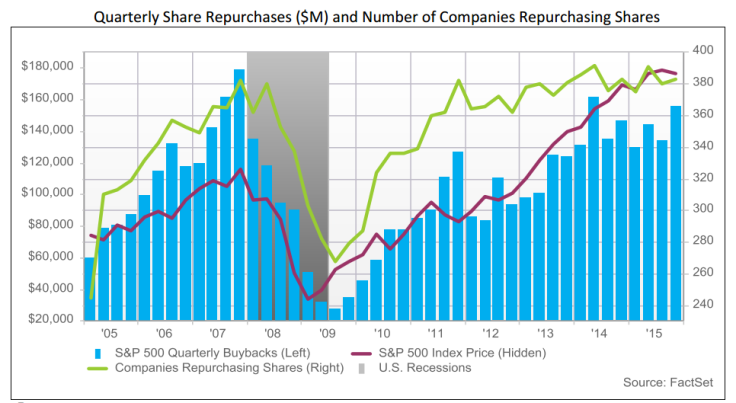

In the 12 months ending in October, buybacks gobbled up $566 billion for companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500, according to FactSet. That’s equivalent to nearly 65 percent of corporate America’s net income for that period.

Studies have found that companies that buy up significant amounts of their own stock invest less, on aggregate, in capital expenditures and see slower revenue growth — though it’s unclear whether the buybacks were a cause of — or a response to — sluggish sales.

“It is a problem that companies are behaving this way,” said Heitor Almeida, a professor of finance at the College of Business at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Almeida’s research has found that companies are likelier to engage in buybacks just before quarterly earnings reports as a way of increasing the closely watched metric earnings per share, or EPS. Reducing the share count increases EPS.

“Executives are willing to spend a significant amount of money to repurchase stock just to make sure they meet the earnings per share target,” Almeida said. He cites research that suggests companies whose executives are compensated based in part on EPS engage in far more stock buybacks.

It’s with that in mind that Fink has encouraged firms to move beyond EPS as the be-all and end-all of financial yardsticks. “Over time, as companies do a better job laying out their long-term growth frameworks, the need diminishes for quarterly EPS guidance, and we would urge companies to move away from providing it,” he wrote Monday.

But Lazonick argued that a longer-term focus wouldn’t rid companies of the incentives to buy back shares. “The whole deal is to get the stock price up,” Lazonick said. “It’s not simply that they’re hitting short-term targets.”

Nick Hanauer, an early venture investor in Amazon and former technology executive, said the pressure to execute stock buybacks in the boardroom is more pervasive than a quarterly push to goose EPS. “No well-meaning CEO can fix this problem on their own,” Hanauer said.

An outspoken critic of shareholder rewards, Hanauer said institutional investors drive the pressure to deliver cash back into the market. “The CFO marches into the board meeting and says, ‘We’ve gotta buy our shares back because our stock is down,’ ” Hanauer said. “In a world where every company drives stock price by buying shares back, you can’t be the only holdout.”

Hanauer and Lazonick support changes in securities law to curtail the practice, and Congress has taken note. Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wis., has publicly questioned the Securities and Exchange Commission on its oversight of stock repurchases. Fink, however, has voiced the more mainstream position that buybacks should remain an option. “We certainly support returning excess cash to shareholders, but not at the expense of value-creating investment,” Fink said in his letter.

Hanauer, recalling his time in the corporate boardroom, argues that good intentions might not be enough to counter the monumental pressure of the markets. “Building better products and services that increase demand? That’s hard,” he said.

But buying back shares shares with spare cash? “That’s the path of least resistance.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.