Nelson Mandela In Ethiopia: A Peacemaker's Beginnings As Guerrilla Fighter

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia -- Flags are flying at half-staff outside the African Union headquarters on Friday in honor of Nelson Mandela, whose death Thursday has the entire continent, and the world, in mourning. The activist, politician, scholar, husband, father and Nobel Peace Prize laureate fought against apartheid, a system of formalized segregation that saw black South Africans treated as third-class citizens, and helped to heal a fractured nation in the aftermath of minority rule.

“Nelson Mandela will be remembered as a symbol for wisdom, for the ability to change and the power of reconciliation,” AU Deputy Chairman Erasmus Mwencha told reporters here in Ethiopia's capital city on Friday morning. “His life and legacy is the biggest lesson, motivation, inspiration and commitment any African can give to Africa.”

But Madiba, as Mandela was affectionately known, was not always a man of peace. Before he capped his career as South Africa's first black president in 1994, before he spent 27 years imprisoned for his anti-apartheid activism, Mandela came to believe that violence was sometimes necessary in the fight for freedom. And it was in Ethiopia that the young Mandela received his first formal training in the art of guerrilla warfare.

At that time, Ethiopia was ruled by Emperor Haile Selassie, who had gained a reputation as a defender of African sovereignty. Mandela was a member of the African National Congress, a then-illegal organization that opposed apartheid in South Africa and is now the country's ruling political party. He had founded the group Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), which would operate as the military wing of the ANC, in 1961. Mandela first traveled to Addis Ababa in 1962 to attend a pan-African summit as a representative of the ANC.

“Ethiopia has always held a special place in my own imagination, and the prospect of visiting Ethiopia attracted me more strongly than a trip to France, England, and America combined,” Mandela later wrote in his 1994 autobiography "Long Walk to Freedom." “I felt I would be visiting my own genesis, unearthing the roots of what made me an African. Meeting His Highness, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, would be like shaking hands with history.” On his Ethiopian Airlines flight to Addis Ababa, Mandela was surprised to find a black pilot in the cockpit, the first he had ever seen.

Mandela went on to visit a host of African countries and meet with leading officials, but at the end of his international tour he returned to Ethiopia for military training. It didn't last long; the young revolutionary was soon called back to South Africa, and in August 1962 he was arrested and thrown into a Johannesburg prison. He would spend the next 27 years behind bars at several different facilities until his final release in 1990.

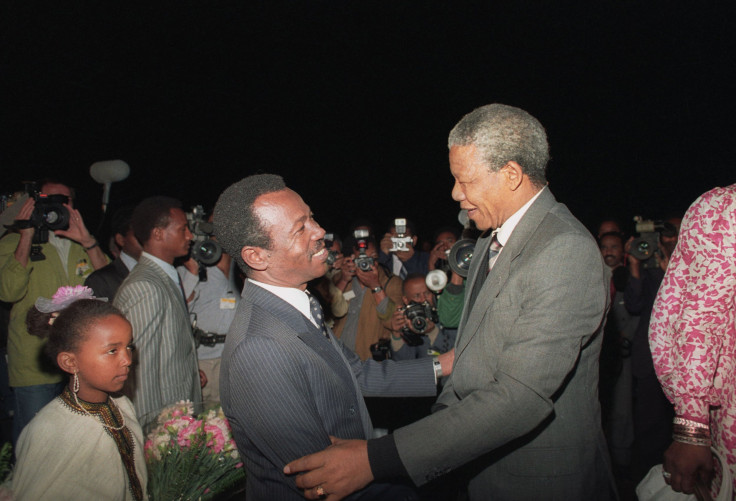

Mandela's visit to Ethiopia was a pivotal moment for many Ethiopians, including Merera Gudina, who now chairs the major political opposition coalition Medrek and still draws on South Africa's anti-apartheid struggle for inspiration.

“Mandela was hosted by one of our best known heroes, Gen. Tadesse Beru, who was at that time the commander of the Ethiopian special forces,” said Merera. “Even during the time of the emperor, people were supporting the cause of South Africans. South Africa was a part of the larger African anti-colonialist struggle.”

Mandela spent only a couple of months training with Tadesse, but he didn't leave empty-handed. There is one artifact that still connects South Africa to Ethiopia, a relic of history whose mysterious disappearance has baffled historians for years. During his time in Ethiopia, the young freedom fighter received a gift from the general to symbolize his struggle: a semi-automatic Soviet-made Makarov pistol. He brought it back with him to the headquarters of Umkhonto we Sizwe in South Africa, a place called Liliesleaf Farm outside Johannesburg, and buried it for safekeeping lest authorities raid the premises.

That was right before his arrest, and five decades later, the gun has yet to be found, despite Mandela's later assertions that it was buried just 20 paces away from where the Liliesleaf kitchen used to be. (The property has been rebuilt and divided up, though the Liliesleaf Trust, as it is now called in it new role as a historical site, remains at its former location.)

Like that elusive weapon, much of Mandela's military history remains underground; his legacy is built on peace, not war. But in Ethiopia and all across Africa, there are some who still think of Mandela not just as an ambassador of peace, but as a man who knew when something was worth fighting for.

Merera says his own opposition efforts owe much to Mandela's struggles. “In fact, our political party took its first name, Oromo National Congress [it is now known as the Oromo Federalist Congress], from the South African National Congress to symbolize the fact that major groups should not fight for secession, but for more equality,” he said. “We are in many ways connected to Mandela and South Africa.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.