New Paxil Warnings For Teens Prompt Fury From Former Patients

Kaili Butin still has faint scars on her wrist from the day she tried to kill herself. A family physician had prescribed GlaxoSmithKline's antidepressant Paxil to treat her depression. It was the fall of 2000, her sophomore year of high school, and she had stopped caring about schoolwork and lost interest in her friends.

“I wanted something to make me feel better,” she says. “I wanted to be a normal teenager. I saw my friends and none of them felt the way I felt.”

Butin was among millions of American teens who took Paxil in the early 2000s. Her doctor's recommendation helped the antidepressant overtake the competition to garner the highest number of new prescriptions of any drug in its class in 2000. Sales of the pill increased by 17 percent to hit $2.4 billion. Butin, now a 31-year-old accountant living in Ankeny, Iowa, is angry about newly revealed information that GlaxoSmithKline withheld from the public regarding Paxil's danger to teenagers.

Butin remembers feeling a change set in soon after she began taking the drug. She wrote furiously in journals to manage her emotional plunge.

“I just remember feeling worthless,” she says. “I had an entire journal of poems that I would write on how horrible life was and how it just wasn't worth being around anymore and everybody would be better off without me.”

After a few weeks on Paxil, Butin began to experience “major rage.” She punched walls and lashed out at friends and family. Her poems became graphic. Eventually, she turned violent toward herself.

"I remember one day, just not even really realizing what I was doing but taking a pair of scissors to my wrists," she says.

When she yelled out in alarm, her mother rushed in and stopped her. After the suicide attempt, Butin says she and her mother thought they needed to give the medicine more time to work. But several months later, Butin felt worse than ever. One night at bedtime, she found herself staring at the eight or nine pills left in the bottle.

“I downed all those and I downed some Tylenol and I remember hoping I wasn't going to wake up the next morning,” she says.

She did wake up — in the middle of the night, sick to her stomach. The next morning, she told her mother what she had done.

“She said, 'That medicine’s obviously not working, and we need to figure something else out,'” Butin says.

Butin tried to kill herself twice in six months while on Paxil. She has never tried to harm herself at any other point before or after taking the medicine. More than a decade and a half later, new evidence suggests what Butin and her mother began to suspect that night — that Paxil may have worsened Butin's depression to the point that she wanted to kill herself.

This month, a team of researchers published a new analysis of a 14-year-old clinical trial data that suggested adolescents who used Paxil were at greater risk of severe side effects — including suicidal thoughts and self-harm — than GlaxoSmithKline originally disclosed. While it’s impossible to know whether her suicide attempts were a direct result of taking Paxil, Butin says she is “very confident” that the drug is to blame.

Specifically, the analysis published in BMJ uncovered 11 cases of suicidal thoughts or self-harm among 275 young adults who took Paxil. GlaxoSmithKline had previously reported just five. Researchers also concluded the drug was no more effective at treating depression than a placebo — a startling revelation for a drug that has been on the market for two decades.

The new analysis — for which researchers perused 77,000 pages of previously unavailable internal records — sparked outrage among former patients and set off a tsunami of criticism of GlaxoSmithKline.

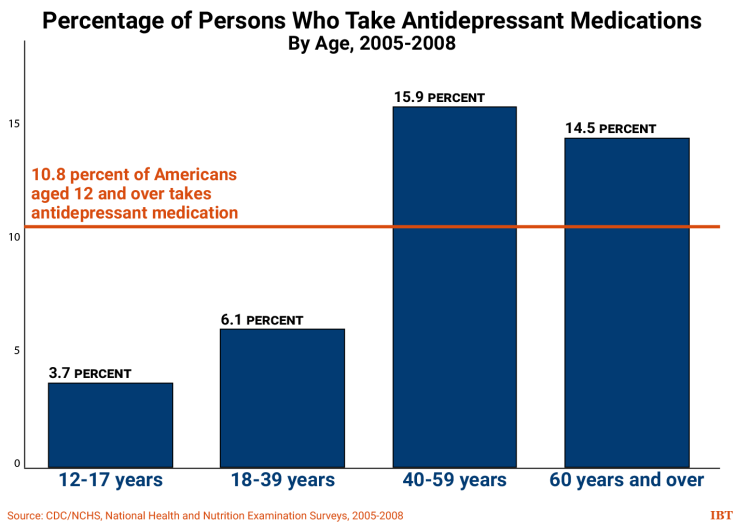

Paxil has been a lucrative treatment for GSK. Doctors wrote more than two million prescriptions for Paxil for teens and children in 2002; use of all antidepressants among young people jumped 36 percent the following year. By 2003, the pill was racking up $3 billion in global sales.

In light of the new findings, the company maintained the original analysis of clinical trial data for Paxil, also called paroxetine, is valid.

“Importantly, the findings from this team’s analysis appear to be in line with the longstanding view that there is an increased risk of suicidality in pediatric and adolescent patients given antidepressants like paroxetine,” the company said in a statement. “This is widely known and clear warnings have been in place on the product label for more than a decade. As such we don’t believe this reanalysis affects patient safety.”

Still, the complete GSK data on adolescents' risk of suicide and self-harm became publicly known only decades after it was first available to the company. Critics say that delay illustrates the inherent problem with the longstanding tradition of permitting drug companies to sponsor clinical trials on the medications they hope to sell.

Now, Butin and others who took Paxil in their teen years are horrified that the scientific evidence to validate their experiences was so slow to emerge.

"The first thought I had was, no sh--, Sherlock. I was like, seriously? They're just now figuring this out?" she says. "I mean, what took so long?"

Within the scientific and medical community, the study was heralded as one of the first cases in which independent reviewers were permitted to comb through clinical trial data. In most cases, such data is carefully guarded by drug companies and reviewed only by the FDA.

GSK voluntarily published the Paxil trials through a new program called RIAT, which stands for Restoring Invisible and Abandoned Trials. RIAT aims to nudge clinical research and drug development toward greater transparency and data sharing, and GSK was the first company to participate.

But before the trials were posted, anyone who took Paxil in their teenage years did not have all the information about the drug’s risks available to them. Those who took it before the warning label was required — including Butin — had even less of a clue. She cannot recall her doctor talking to her about the potential side effects of Paxil.

Feeling Hopeless

Breena Vickers, 31, of Dunedin, Florida, says she feels strongly that Paxil put her in a dangerous state of mind when she took the drug as a 15 year old. Just days after she swallowed the first pill, her mood plummeted and “things started getting really bad."

Vickers’ mother told her to stick with the medicine because she believed it would ultimately help. But two and a half weeks after starting Paxil, Vickers could no longer see the point of living. So she decided to stop.

“I tried to cut my wrists and my father literally wrestled a straight razor out of my hands,” she says.

Just a week later, Vickers reached into her mother’s medicine cabinet for a bottle of Vicodin and swallowed all the pills at once. She became violently ill and fell into a deep sleep.

When she woke up, she thought about what had changed in the past few weeks and decided to stop taking Paxil.

“It clicked in my head — I'm trying to kill myself," she says. "I'm trying to end my life and this is not what normal people do."

About three days after she stopped treatment, she began to feel better. She sought out her friends and became interested in school again. She hasn’t taken Paxil or any other antidepressant since, and instead she sought behavioral therapy until she was 17 to cope with depression.

Vickers attempted suicide twice in just four weeks while on Paxil. Similar to Butin, she did not try to end her life at any point before or after treatment.

Too Little, Too Late?

Paxil is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), a class of drugs that includes Prozac and Zoloft. SSRIs have been shown to elevate mood by preventing the brain from reabsorbing a neurotransmitter called serotonin.

Antidepressants often demonstrate low efficacy in clinical trials. In reality, some patients may respond very well even if the vast majority does not respond at all. It’s common practice for doctors to cycle through antidepressants to see which one elicits the best response in each patient.

Psychiatrists who prescribe antidepressants to adolescents know that Paxil carries some of the most dramatic side effects among SSRIs. For that reason, doctors have exercised extreme caution in offering the drug to teens or phased out its use in adolescents entirely.

"We know it can work for some people but it certainly does have a lot of warts in terms of side effects and tolerability concerns," Dr. Jerry Halverson, a psychiatrist and medical director at Rogers Memorial Hospital in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, says.

In 2003, the Food and Drug Administration recommended Paxil not be given to teens at all. In 2004, the agency required GSK to feature a prominent warning label regarding the drug’s use in adolescents. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Justice required GSK to pay nearly $3 billion partly for inappropriately marketing the medication as effective and safe for teens.

The company has also settled multiple class action lawsuits in which plaintiffs argued that Paxil was dangerous and ineffective for adolescents and children, including a $63.8 million agreement with consumer watchdog group Public Citizen in 2007.

Amanda Scott, a 31-year-old woman who lives in Pennsylvania, says she never would have begun taking Paxil at the age of 13 if she knew what she knows now. She initially felt a boost in her mood after taking the pills in 1997. But after a year, that feeling wore off. She told her psychologist that she was considering suicide.

“I had a plan which is something I never had before,” she says.

After that disclosure, Scott was hospitalized for five days. When she was discharged, her doctors increased her dosage of Paxil. She remained on the medicine for another year. During that time, she thought about killing herself every day and would cut her arms about once a month.

Though she tried to kill herself on nine different occasions between the ages of 13 and 19, she recalls a “cluster” of attempts during the period when she took Paxil, including overdosing on aspirin.

She told her psychologist and psychiatrist about every attempt, but does not recall ever discussing a potential connection to Paxil or the many other antidepressants that she would cycle through in later years.

“I wanted help, I didn’t want to feel like this,” she says. “We never suspected that it was the drugs that were the problem and the response was always to give me different drugs.”

But when Scott read about the new study, she felt she finally had an answer.

“It made sense to me because I knew what I went through,” she says. “I think it started me on a very bad track that pretty much just took my entire teenage years away.”

A Serious Message

Dr. Jon Jureidini, a research psychiatrist at the University of Adelaide in Australia and the lead author of the new analysis, urges psychiatrists to take the results of the new analysis seriously.

“Paxil shouldn’t be prescribed to anyone under 25, and probably not at all,” he says.

Meanwhile Dr. Martin Keller, a retired psychiatrist at Brown University who led the original research, echoes the company's sentiment.

“We see nothing in the reanalysis in the BMJ article that would change the treatment of adolescent depression for a contemporary clinician using evidence-based treatment,” he says

Dr. Greg Simon, chair of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance’s Scientific Advisory Board, calls for a more focused effort on such research questions as: How can we find depression treatments that have better average effectiveness? How can we better match individuals to the right treatment?

Vickers was sitting on her couch at home when news of the Paxil study popped up in her Facebook news feed. She could instantly recognize the study’s significance, even if today's psychiatrists feel like its results are underwhelming.

“I was like — oh, oh really, they're just now finding this out!? I could have told them that 10 years ago!” she says. “I was outraged.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.