The Promise Of Telehealth: States Push For Insurance Coverage As Support For Virtual Healthcare Services Swells

Clifford Seetook lives in Wales, Alaska, a town of only about 150 permanent residents on the state's western lip. When the 62-year-old retired custodian began feeling pain in his hip and knee last spring, he visited the village's clinic for physical therapy because "you've got to keep moving," he says.

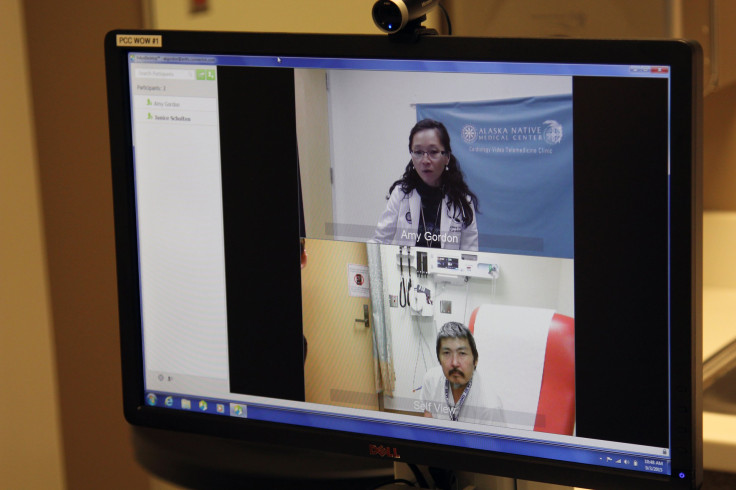

But there wasn't a physical therapist within a hundred miles, and a round-trip flight to Fairbanks or Anchorage costs about $1,000. So a health aide helped him log on to a virtual office visit with a physical therapist based in Nome. Seetook learned exercises over six online sessions and managed his pain well enough to remain at home while awaiting surgery this fall.

"It made things a lot easier for myself and the physical therapist to communicate," he says. "That gave me a lot of courage."

For decades, proponents of telehealth, also known as telemedicine, have pushed for the expanded use of communications technology to deliver healthcare services to underserved areas -- both urban and rural -- to help patients like Seetook. In its various forms, telehealth has been shown to expand access to care, reduce wait times for appointments, lower the cost of healthcare and improve patients' health. Analysts at Towers Watson have predicted that U.S. companies could save as much as $6 billion in healthcare costs if all employees used telehealth coverage to the greatest possible extent. However, supporters have struggled to persuade insurers and government healthcare programs -- especially Medicare, the nation's healthcare insurance for people who are at least 65 years old -- to cover these services at rates comparable to those physicians receive for treating patients through traditional visits.

"The goal of telemedicine is to get healthcare out to where the person is," says Jonathan Linkous, CEO of the American Telemedicine Association, a group that estimates roughly 12 million Americans used some form of telehealth in 2013. Linkous suspects the number has doubled since then.

Medicare only covers telehealth for a limited number of patients in designated rural areas, and those patients must still travel to a clinic to complete a session rather than log in directly from home. As a result, only 1 percent of Medicare beneficiaries use telehealth each year.

And since Medicare coverage is used as a benchmark for grant funding and private insurers to set their own rates, investment has been limited since telehealth debuted in the 1990s.

"How do you expect a provider to provide these services through telehealth if they don't get paid for it?" Mei Wa Kwong, senior policy associate at the Center for Connected Health Policy, says. "It kind of holds it back."

But that may soon change, as multiple federal campaigns aim to relax Medicare's restrictions and provide patients with greater access to telehealth services. If successful, these changes could have a domino effect by demonstrating the value of these services more broadly as support for telehealth builds in the private sector and among consumers.

Telehealth is a vague term -- the federal government has seven definitions for it -- but in its most popular form, a patient consults a doctor about a rash or sore throat over a quick video consultation. The American Telemedicine Association estimates at least 450,000 patients have engaged in 800,000 online doctors visits in the past year.

In other instances, telehealth means installing monitoring equipment in the home of a patient with heart failure so that doctors can keep an eye on their weight – a sudden change can indicate fluid buildup. It can also mean having a nurse use a portable device to take a patient’s blood pressure at a rural clinic and forward that data to a physician (a practice known as “store and forward”).

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has proposed expanding Medicare coverage of telehealth services to permit rural health clinics and qualified healthcare centers to use technology to monitor and manage patients with chronic diseases such as end-stage renal failure in their own homes. The revision, which is under review, stopped short of expanding coverage to all Medicare beneficiaries regardless of location, or of permitting in-home video consultations.

Legislators in the House and Senate introduced an act this summer to pay physicians for telehealth delivered to Medicare beneficiaries in any location, to include physical therapists and speech language pathologists among the clinicians eligible for reimbursement and to permit physicians to treat patients from other states without physically meeting them first. Last month, 21 organizations including the American Telemedicine Association and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce co-signed a letter in support of the act, though previous versions failed to gain much traction in Congress.

These measures at least indicate burgeoning interest at the federal level in incorporating telehealth more broadly into the healthcare system. In the private sector, momentum is building more rapidly. This year, UnitedHealthcare pledged to provide clients 24-hour access to video visits for conditions such as allergies, bladder infections and bronchitis through their laptops or phones. Walgreens announced it would offer similar access to customers in 25 states through Walgreens.com, while CVS is conducting pilot tests to provide telehealth to customers through its nationwide network of MinuteClinics. The pharmacy chain is working with a startup called Teladoc, which employs 700 physicians and went public in July.

Doctors and hospitals are embracing the idea, too. The Cleveland Clinic and University of Washington Medical Center have both started online clinics this year where residents of Ohio and Washington pay less than $50 for a virtual visit for colds, the flu, sore throats and urinary tract infections.

"Now, increasingly, it's what consumers want," Linkous says.

Fueled By States

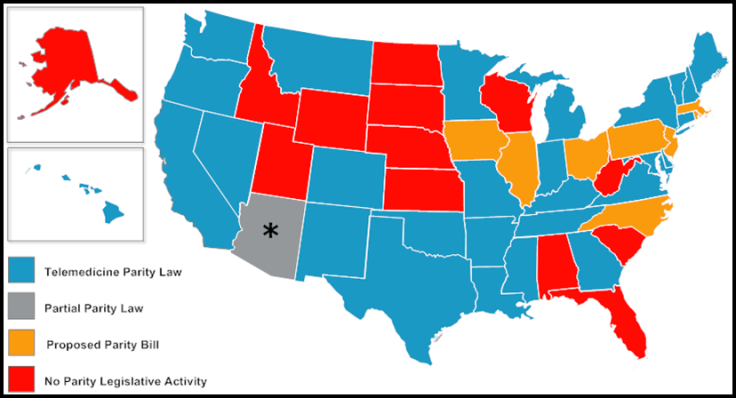

States have largely driven the build-out of telehealth networks in the U.S. While Medicare lags behind, 29 states and Washington, D.C., have adopted parity laws to require private insurers to provide some degree of telehealth coverage. Eight more are considering legislation to do so.

"Telehealth is something we've seen an uptick in interest in recently," Kate Blackman, a policy associate at the National Conference of State Legislatures, says "I think we're seeing it as a bipartisan issue and it's really being driven by the triple aim -- achieve better health and better care while reducing healthcare costs."

However, the resulting patchwork of policies leaves residents in some states with less access than others. For example, states offer varying degrees of coverage through Medicaid programs for low-income residents. Blackman says nearly every state reimburses residents for virtual visits but less than half pay for store and forward or remote monitoring.

Alaska was an early pioneer in extending telehealth to rural residents in particular. Like Seetook, many of the state’s 150,000 Alaska Natives live in distant villages where road access is considered a luxury. These residents receive healthcare through the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, which is backed by multiple streams of funding from the federal government, tribal governments and Alaska Native regional nonprofit organizations.

"Our biggest challenge in providing healthcare is where people have to pay $900 to get on a plane and fly through bad weather or over mountains," Stewart Ferguson, chief technology officer, says.

The group launched telehealth in 2001 and has since brought these services to more than 200 sites throughout the state. Today, every single Alaska Native has access to telehealth. About 17 percent of patients, or 27,000 people, use it each year -- mostly to seek primary care. The entities that fund it would otherwise foot a much higher bill for the cost of transporting patients to a nearby city. Ferguson estimates that the consortium saves about $8 million a year on transportation costs alone.

But the potential reach of this model to other rural areas is limited, because payers elsewhere do not absorb the cost of getting patients to a doctor. Therefore, their cost savings may not be as great.

Another twist is that even though telehealth was originally conceived as primarily a service to rural residents, its biggest potential market may turn out to be urbanites.

"It started out 20 years ago as primarily a rural program funded by grants and that's still very important, but the growth is where the people are and that's in urban areas," Linkous says.

Dr. John Scott, director of the University of Washington's telehealth services, says since the school's medical center launched its virtual clinic in January, physicians have fielded about 800 calls. Though they accept patients from anywhere within the state, about 65 percent of the calls have been from patients who lived within five miles of the hospital.

"It's a tool that helps the underserved and you can have underserved folks who live in rural and urban areas," Kwong, senior policy associate at the Center for Connected Health Policy, says. "In LA, you can be smack dab in the middle of the city and if you need a specialist, you may have to take two or three buses to get to that specialist."

Even though Medicare has shied away from coverage, the federal government has supported telehealth in both urban and rural areas through other means -- particularly through grants that helped build programs such as the one in Alaska. Carlos Mena, a public health analyst in the Department of Health and Human Service's Office for the Advancement of Telehealth distributes grants totaling $15 million to about 20 telehealth projects at hospitals and universities each year. Those recipients facilitated about 760,000 telehealth "encounters" between patients and physicians from 2004 and 2010 which include everything from psychiatry to diabetes counseling. Overall, the program saved $38 million in healthcare costs and $41.7 million in travel costs during that period, according to the department's Office of Planning, Analysis and Evaluation.

So far, the grants have only been given to facilities that already had an existing telehealth network in place, but Mena says this year his office will begin accepting applications from institutions that would like to build one from scratch.

No Guarantees

Amid the growing enthusiasm, Dr. Quianta Moore, a health policy expert at Rice University, is careful to point out that telehealth is not guaranteed to save money or improve care. In some cases, making it easier for patients to access care may encourage them to use it more frequently, thereby driving up costs. And rural patients who are said to benefit so much from these services often had no other access to care in the first place, and so their visits will represent a new cost to the system.

"People always tout telemedicine as a way to save money, but there are times when this either fails miserably or else is really expensive," she says. "I think sometimes with technology, people skip over the fundamentals."

British researchers found that installing equipment to monitor patients at home produced only minor improvements in quality of life and did not meet the benchmark for cost effectiveness required by the U.K. health system. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office has struggled to answer the question of whether expanding telehealth services under Medicare would ultimately help or hurt the federal budget. In the end, administrators said they needed more research to make a recommendation.

"In certain instances, there's some great evidence around telehealth, but we need more evidence around how it's being utilized and to what extent it's improving outcomes and reducing costs," Blackman says.

This year, Mena's office will fund a brand-new telehealth research center to take aim at a few of those unanswered questions on a large scale. Decades after telehealth first came into use, it will be the first research grant the office has ever supported.

"We really need this data from the federal perspective," Mena says. "There's very little research data to support telehealth and to demonstrate that it's cost effective and improving access to care, especially for rural patients."

Last year, Ateev Mehrotra of the Rand Corp. told the House Subcommittee on Health that if lawmakers are interested in saving money, they should use telehealth to prevent costly visits to the hospital or emergency room. Programs which simply supplement traditional doctors’ visits may not be able to pay their way.

Linkous at the American Telemedicine Association thinks these concerns are overblown.

"People are worried that if we do telemedicine, everyone's going to access healthcare and drive up costs," he says. "But after 23 years of working in this industry, I can tell you it does not drive up costs -- it saves costs."

The Future Of Telehealth

The demand for telehealth is clearly growing. Researchers at Tractica say the number of people using telehealth globally will accelerate from 14.3 million in 2014 to 78.5 million by 2020. In addition, the research firm RNCOS projected the global market for telehealth products -- built by companies such as Philips Healthcare, GE Healthcare and Ceerner -- would expand at a compound annual growth rate of 18 percent from $17.8 billion in 2014 through 2020.

But in the U.S., building a strong case through data and persuading lawmakers to permit Medicare reimbursement will only remove a few of the barriers to incorporating telehealth into the healthcare system. Under the current rules of most of the nation's 70 state medical boards, physicians who are licensed in one state cannot legally treat patients elsewhere. The Office of Telehealth Advancement has given the Federation of State Medical Boards about $300,000 a year throughout several grant cycles to solve this problem. But the American Telemedicine Association still refused to give out a single "A" to any state in its most recent report card for licensing policies.

Among doctors, there are still hints of hesitancy about how telehealth will impact their relationships with patients or their practice's bottom line. The American College of Physicians issued guidelines on Monday to primary care doctors who wish to incorporate telehealth into their practice, but emphasized that the technology should only be used after a physician has met a patient face to face.

"I think because the reimbursement has always been an issue, many of the specialties have not really opened up," Scott, at the University of Washington, says.

Kwong believes that despite the remaining barriers, patients are destined to drive payers and providers to offer the convenience of telehealth.

"Consumer demand, I think, will help push the health systems toward telehealth," she says. "They'll say -- 'Why do I have to drive a half hour to see my doctor? I could have done this over my computer.'"

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.