Is Right-To-Work Key To Job Growth? West Virginia, Other States Tackle A Heated Question

West Virginia — a former union bastion whose embattled coal mines once hosted some of the most fabled labor battles in American history — could soon become the latest state in the nation to pass a so-called right-to-work law. On Thursday, the state's Senate approved such a measure, officially kicking off a legislative fight that is expected to come down to the wire.

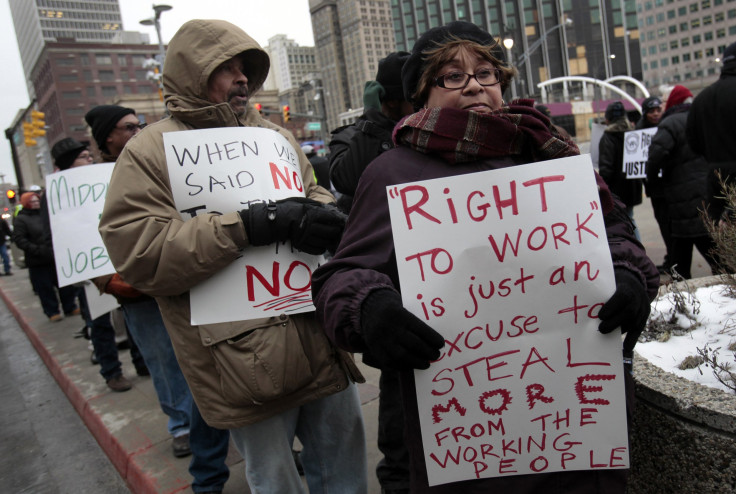

It’s one of a handful of states expected to closely consider right-to-work bills this year. The laws have implications that extend well beyond the declining share of the unionized workforce. Critics say the laws, which prevent unions from charging fees to non-members, depress wages and hurt workers’ bargaining power. Backers say they’re the key to much-needed investment and job growth. At any rate, the stakes are especially high in West Virginia, one of the poorest states in the nation grappling with the painful decline of the coal industry.

“Business and industries where unions are more prevalent prefer to locate in states with right-to-work laws,” said James Sherk, a research fellow in labor economics at the conservative Heritage Foundation.

In high-paying industries that don’t tend to attract unions in the first place — say, tech companies like Google or Facebook — it may not matter. “But in something like manufacturing, it does have a large effect,” Sherk said.

That’s precisely the argument of business groups behind the proposed legislation, such as the West Virginia Chamber of Commerce.

“States that have passed [right-to-work] have signaled to potential employers that they want job growth in their state and [West Virginia] is in no position to turn away this growth,” the chamber argued on its website. “New and innovative policies are necessary to compete in today’s job market and if [right-to-work] has an impact, we need to pass it.”

The evidence, though, is anecdotal at best. Perhaps the best-known example is the auto industry: Over the last couple of decades, foreign automakers such as Volkswagen, Nissan, BMW, Mercedes-Benz and Volvo all opted to build new assembly plants in the largely right-to-work and union-free U.S. South rather than traditional auto bastions like Michigan or Indiana, which at the time did not have such laws on the books.

Still, Josh Sword, secretary-treasurer of the West Virginia AFL-CIO labor federation, noted that proponents have failed to identify a single employer that has signaled it would move to West Virginia if the state passes right-to-work. The state’s commerce secretary acknowledged as much during a recent senate committee hearing.

“We’ve never been recruiting a business who said ‘no’ because of right to work,” Keith Burdette, who is a Democrat, said last week. “If you asked me for a list of companies that will not look at a state that is not right-to-work, I can’t produce that list.”

Josh Sword of the AFL-CIO also said the laws depress wages — for union members and non-members alike.

Under federal labor law, unions are legally obligated to represent all workers in any bargaining unit where they obtain a majority of support — say, at a specific factory or mine. Employees who choose not to join are often required to pay fees under contracts negotiated between the union and the employer. Right-to-work laws explicitly prevent these sorts of arrangements. According to critics, the laws remove incentives to join the union and as a result, cash-strapped unions struggle to negotiate strong contracts and adequately represent workers’ interests in the political arena.

Workers in states without right-to-work laws, such as New York or California, tend to earn more than those in states that do, like North Carolina or Alabama. But it’s hard to know exactly how much of that has to do with right-to-work.

When it comes to wages, researchers on both sides of the debate have published studies with dueling conclusions. The left-leaning Economic Policy Institute has found workers in right-to-work states earn three percent less than their counterparts in other states after controlling for various demographic, socioeconomic and macroeconomic factors. Meanwhile, James Sherk’s research shows that private-sector workers in right-to-work states earn about the same as those in non-right-to-work states.

What’s clear is the right-to-work backers have the political momentum. Kentucky and Missouri are also expected to take up right-to-work bills this year. Last year, Wisconsin became the 25th state to pass such a law, joining other recent converts, Michigan and Indiana.

In West Virginia, the GOP majority House is soon expected to take up the bill, although observers anticipate its passage will be met with a veto by Democratic Gov. Earl Tomblin. That’s when it gets interesting: A majority in both legislative chambers is required to override the veto. Right now, Republicans have just a single-vote edge in the Senate. That’s down from a two-vote margin after a former Republican legislator — originally elected as a Democrat — resigned to take a lobbying position with the National Rifle Association. The West Virginia Supreme Court will soon decide whether Gov. Tomblin can appoint a Democrat to that vacant position, the potential difference between a 18-16 or a 17-17 vote along party lines.

Sword acknowledged a lot hinges on the Supreme Court ruling. But he said his side hopes to sway Republicans in the meantime, appealing to their conservative principles.

“This is the government interfering in the relationship between workers and employers, saying you can negotiate everything except for this,” Sword said. “A lot of the people voting for this are the same ones who are saying how the free market knows best.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.