Stuyvesant High: Asian-American Domination In Elite Schools Triggers Resentment, Soul Searching

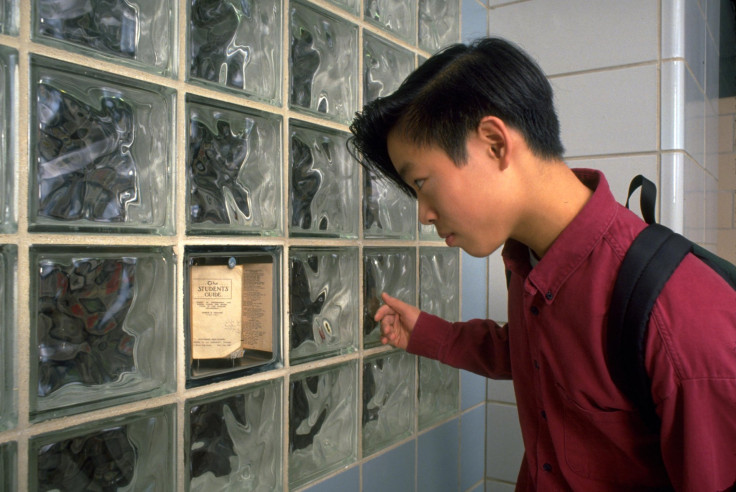

The rise of Asian-Americans and their dominance in academia may be exemplified by the extraordinary performance of Asian-American students in New York City.

According to recent media reports, Asian-American students account for almost three-fourths of the enrollment at Stuyvesant High School, one of the city's eight specialized, elite public schools that strictly use test scores for admission. Asians represent less than 14 percent of the city's entire public school student body, meaning they are disproportionately represented at Stuyvesant by a magnitude of about five. (In 1970, Asians accounted for only 6 percent of Stuyvesant’s student body.) Whites, including Jewish students whose numbers made them prominent as a group at the school, now represent less than a fourth (24 percent) of Stuyvesant’s enrollment, down from 79 percent in 1970.

In stark contrast, the enrollment of blacks and Hispanics (who together account for about three-fourths of the city's entire public school system) at Stuyvesant is almost minimal -- and falling. According to the New York Times, only seven black students were admitted to Stuyvesant this year (down from nine last year), while the number of Latinos dropped from 24 to 21. (Stuyvesant has a total enrollment of about 3,300.)

At two other prominent elite public schools in New York, Brooklyn Technical High School and Bronx High School of Science, the number of black pupils is also small, and it's declining compared to previous recent years, the Times noted. For example, black enrollment at Stuyvesant peaked in 1975 at 12 percent of the student body.

Some critics blame the low enrollment of blacks and Hispanics at Stuyvesant (and the other specialized schools) on one principal factor: their lack of access to test preparation academies and tutoring classes.

Reportedly, many students in impoverished black and Latino neighborhood schools are not even aware of the testing procedures and how to prepare for them, nor can many afford the costly classes to train for these crucial pretest examinations.

The city's Education Department said that 28,000 students across the city took the “Specialized High School Admissions Test” last year, and about 5,700 of them were offered admission to the elite schools. Of that figure, 53 percent were Asian, 26 percent were white, but only 5 percent were black and 7 percent Hispanic.

Two of the city's most powerful voices, newly elected Mayor Bill de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña, have called for a revamp of admission policies and procedures.

"We must do more to reflect the diversity of our city in our top-tier schools -- and we are committed to doing just that," Fariña told the Daily News. "In the coming months we will be looking at ways to address the gap that has left so many of our black and Latino students out of specialized high schools."

De Blasio, whose mixed-race son, Dante, attends one of the elite public schools, Brooklyn Tech, has promised to change the admissions procedures, although any proposal he makes is subject to approval by the state Legislature in Albany, which made the single-test admission requirement state law in 1971.

“These schools are the jewels in the crown for our public school system,” de Blasio said at a news conference. “This is a city blessed with such diversity. Our schools, especially our particularly exceptional schools, need to reflect that diversity.”

Karim Camara, a Democratic assemblyman from Brooklyn, is preparing a revised bill that would give the city power to control admissions rules in the elite public schools.

The Brooklyn Reader reported that Reginald Richardson, a high school principal in Brooklyn, said that while the enrollment numbers for blacks and Latinos at elite public schools are unacceptable, the root problem is that there are insufficient educational opportunities available to non-Asian minorities, and the main problem is not the testing.

“These outcomes tell us that the education that black and Latino kids are receiving in the elementary schools and middle schools in the city is poor, and that they’re not able to be competitive,” he said. “But those same kids are going to have to sit for the SATs when it’s time to go to college, and you won’t be able to change the metrics for the SATs. We need to address the fundamental problem of all kids getting a great education. And that’s not happening in the city. And these results of these entrance examinations in the schools are just evidence of it.”

Academics are divided over these various issues: why Asians perform so well academically, and whether testing should be the sole basis of admission to top schools.

Guofang Li, an associate professor of second language and literacy education in the Department of Teacher Education of Michigan State University, is one scholar who does not believe that admission-by-testing is unfair to anyone.

“In a culture where Asians are still a minority group -- and often marginalized in society-- tests are actually providing a good pathway for Asians to get opportunities like ... attending a good school with good resources ... which can help them get into a better university and hopefully better employment in the future,” she said in an interview.

But Jennifer Lee, a professor of sociology at the University of California, Irvine, believes that admission testing is quite unfair to economically disadvantaged Hispanics and blacks.

“Access to unequal resources will result in unequal outcomes,” she said. “Until we can provide adequate resources for all New York City children to prepare for admissions tests, we will continue see racial disparities in admissions to schools like Stuyvesant.”

On the other side of the argument, Li believes that applying affirmative action-type policies to public school admissions would be disastrous.

“[Stuyvesant] is diverse, just [with] different [racial] ratios,” she said. “Normally, most schools in suburban areas are 75 percent white and 25 percent other ethnic groups, while urban schools [may typically have a] 75 percent black or Hispanic population and 25 percent other ethnic groups." She noted that such school racial compositions are accepted by most people as “diverse,” but when Asians form the dominant ethnic group (as in Stuyvesant), suddenly questions and complaints arise.

“I do think people have a perception [of] what a diverse school has to be,” she said. “[But] if Asians are in good schools, they have a problem with it.”

Jerome Krase of the sociology department at Brooklyn College-CUNY, author of “Seeing Cities Change: Local Culture and Class,” said that if de Blasio and Fariña want to change admission policies at elite high schools, it would defeat the schools' very purpose. But he does see race playing a role in denying opportunities to blacks and Latinos.

“[It would be] better to improve the local schools and improve the life conditions of those who are disadvantaged,” Krase said. “They could also make sure that all schools provide the best education possible for all students. [But] this is not likely, because it means paying higher taxes to help other peoples' children. New York City and Americans in general are no longer as generous when it comes to helping those in need, especially as the composition of those in need have become less 'European'.”

Asians in New York City, who comprise a broad array of ethnic groups, including Pakistanis, Chinese, Indians, and Koreans, among many others, are uncomfortable with comments suggesting that there are “too many” of them in the metropolis’ best public schools. This perception puts many Asian students and their families on the defensive about their cultures’ emphasis on education and personal sacrifice, and many feel it also can lead to racially biased statements about the work habits and intelligence of other ethnic groups.

Jan Michael Vicencio, a Filipino student at Brooklyn Tech, explained to the Times how Asian students are both ridiculed and praised for their academic excellence. “You know, [other kids say] ‘You’re Asian, you must be smart,’ ” he said. “And you’re not sure [if] it’s a compliment or an insult. We get that a lot.”

Other Asian students point out that parental discipline and rigorous scholarship, which are common in their cultures, explain their relatively superior performance in American schools, not any innate intelligence or intellectual superiority.

“Most of our parents don’t believe in [the word] ‘gifted,’” Riyan Iqbal, a son of Bangladeshi immigrants and a student at Bronx Science, said. “It’s all about hard work.”

Citing the poverty and hardships his family experienced in their native Bangladesh, Riyan added: “You try to make up for their hardships. I knew my parents would still love me if I didn’t get into Bronx Science. But they would be very disappointed.”

Asians in general value education, according to Li.

“[The] education of their children is often a family affair, and the whole family [invests] a lot of time, resources and efforts, even soon after a child is born," Li said. "Many Asian families invest a lot of money [in] their children's studies, including preparing for exams and tests."

But, again, Lee takes a somewhat different view on why Asians perform well on tests. She says that some Asian immigrants -- especially Chinese, Koreans and Vietnamese -- hail from countries where the only means of gaining admission into universities is through a rigorous, national entrance exam.

“So, they are more accustomed to the practice of test-taking for school admissions,” Lee said. “And because of the high stakes of students’ performance on this test, Asian parents are more likely to invest their resources in supplemental education for their children to ensure that they perform well on these tests.”

Lee added that some of this supplemental education is offered at no or little cost in ethnic communities through community organizations, while churches also help poor and working-class Chinese overcome their class disadvantages.

“So it’s not that certain groups or certain cultures value education more than others,” Lee insisted. “All groups value education. Rather, groups have differential access to available resources to help them gain access into these competitive magnet schools.”

Lee noted that Asian immigrants tend to come from countries in which effort, rather than ability alone, is hailed as the route to achievement.

“Because Asian immigrant parents believe that increased effort leads to continuous improvement, they are more likely to invest their resources in supplemental education for their children compared to native-born American parents,” she said.

On a national basis, some Asian immigrants and Asian-Americans are both puzzled and outraged over quota and affirmative action programs that hurt them despite their status as “racial minorities.”

Irwin Tang, an Austin, Texas-based psychotherapist, told Diverse Education that he believes some of the nation's elite universities impose “unofficial” quotas to limit Asian enrollment, as they once did for Jews. According to reports, up to 18 percent of Ivy League school students are now of Asian descent, and Harvard’s incoming class last year was more than one-fifth Asian. At Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 28 percent of students are Asian-American, while at University of California at Berkeley, the figure is 39 percent.

“Affirmative action lowers the bar for black and Hispanic students,” Tang said. “They don’t have to score high or have as high of a GPA compared to an Asian student. That’s why many Asian students are being advised not to reveal their race.”

Tang added that he would like to see high schools and elementary schools improve across the board. “The solution is not affirmative action. The solution is to have equal standards for everyone and an improved education system,” he said.

Ron Unz, the publisher of the American Conservative magazine, wrote in an op-ed in the Times in December 2012 that quotas on Asians at Harvard and other elite colleges -- the allegations are widely denied by university officials -- echo similar quotas imposed on Jews decades ago. Unz argued that while the Asian-American population has about doubled since the early 1990s, their presence in Ivy League institutions has either remained flat or fallen slightly.

“The last 20 years have brought a huge rise in the number of Asians winning top academic awards in our high schools or being named National Merit Scholarship semifinalists,” Unz wrote. “It seems quite suspicious that none of [these] trends have been reflected in their increased enrollment at Harvard and other top Ivy League universities.”

Despite the stellar performance of Asians in U.S. high schools and colleges, their ascendance to high positions in corporations has not caught up.

“Many outstanding Asians from top colleges often experience barriers to promotion and advancement at work,” Li said. “Few Asians are in leadership or management positions [at top firms].”

Indeed, a report by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission from 2008 revealed that Asians experience multiple forms of discrimination in corporate America.

There is also a separate issue to consider -- given how bewilderingly diverse and large the Asian-American community is, not all segments of this group are doing well, either academically or professionally. Generally speaking, Chinese, Japanese, Koreans and Indians have excelled academically and earn higher-than-average incomes. But, other Asians, particularly Bangladeshis and some Southeast Asians (e.g., Cambodians, Hmong, Laotians, etc.) remain poor, undereducated and underemployed. These facts would seem to provide evidence that “Asian cultural values” do not necessarily guarantee success, given some harsh socio-economic realities.

“It is critical to underscore that ‘Asian-American’ is a broad and diverse category that includes immigrant groups who arrive as highly selected and highly educated, as well as others who arrive as poorly educated immigrants or refugees with little formal education and few skills,” Lee said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.