World’s Smallest Mona Lisa Created, Painting Is Thinner Than Human Hair [PHOTOS]

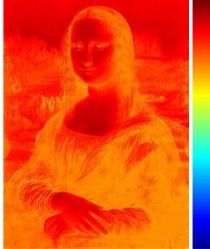

Mona Lisa’s smile has been recreated on a microscopic scale.

The world-famous painting has been “painted” on a surface that is approximately 30 microns in width, roughly one-third the width of human hair. Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology recreated the world's smallest version of Leonardo Da Vinci’s masterpiece in an attempt to demonstrate a technique that can be used for nanomanufacturing.

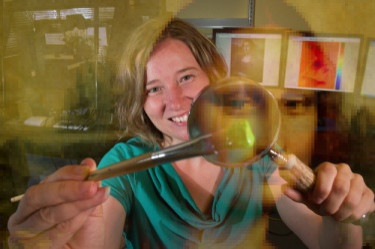

The black-and-white Mona Lisa copy was created using a microscope and process known as ThermoChemical NanoLithography. Using a precise application of heat, the team proceeded pixel by pixel to apply the right amount of heat to get the color of grey it desired. The more heat used, the darker the surface area became, Popular Science reports.

"By tuning the temperature, our team manipulated chemical reactions to yield variations in the molecular concentrations on the nanoscale," Jennifer Curtis, an associate professor in the School of Physics and the study's lead author, said in a statement.

Researchers say the technique could be used to create chemical gradients to perform experiments in nanoelectronics, optoelectronics and bioengineering that have been previously impractical. Since the technique is “relatively straightforward,” researchers say it can be used in both academic and industrial laboratories.

TCNL, the technique in question, could be used to create proteins, DNA and nanoparticles, according to the Georgia Tech researchers who developed the process in 2009.

“We’ve created a way to make independent patterns of multiple chemicals on a chip that can be drawn in whatever shape you want,” Curtis said. He added that TCNL is fast, moving at 1 millimeter per second.

“It allows scientists to very rapidly draw many things that can then be converted to any number of different things, which themselves can bind selectively to yet any number of other things,” said Seth Marder, professor at Georgia Tech’s School of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.