Technology Focus: The SOPA Soap Opera

Is Ben Franklin around?

Internet users sighed with relief last week when top congressional leaders pulled the plug on two proposed laws to govern the Internet, the Stop Online Privacy Act (SOPA) and Protect IP Act (PIPA).

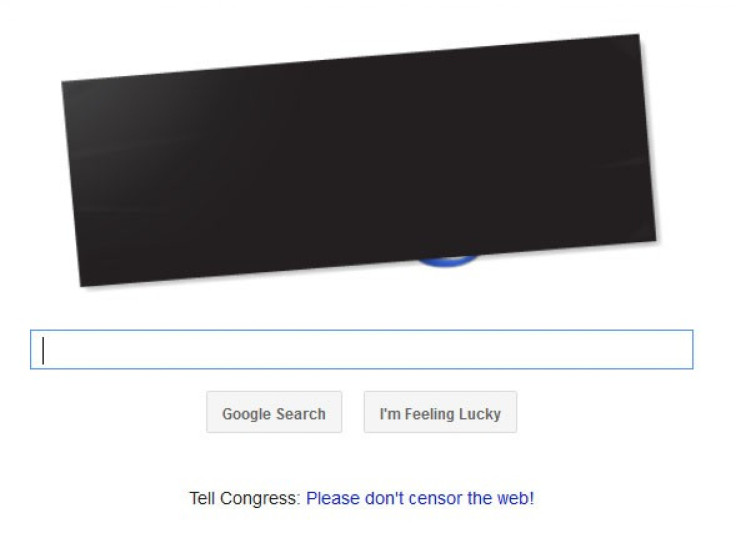

After global protests on Wednesday which saw darkened Websites like Wikipedia and BoingBoing and a virtual strike by Google, on Friday, SOPA, a creature of the U.S. House of Representatives, and PIPA, in the Senate, were essentially smothered.

Why did either of these proposed laws get so far in the first place? Hadn't their respective sponsors, House Judiciary Committee Chairman Lamar Smith (R-Tex.), 64, and Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), 71, ever read the First Amendment:

Congress shall make no law restricting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peacefully to assemble, and to petition the Government for the redress of grievances.

It makes you wish Benjamin Franklin were still alive. Surely this printer, scientist, entrepreneur, diplomat and statesman would have known how to deal with the sticky issue of piracy in the Internet era. Or would he?

After the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 and the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act of 2011 became law, major publishers and Hollywood studios still believed they had inadequate protection from thieves in the Internet era. In a way, they were right, because with servers and the web, offshore pirates do indeed make available someone else's material for viewing or private use.

Indeed, amid last week's SOPA-PIPA protests, it was noteworthy that some of the major technology companies that zealously run to court over alleged IP infringements - Apple, Intel, IBM, Hewlett-Packard and Texas Instruments - were silent.

Part of the genius of Steve Jobs, a modern Ben Franklin, may have been his insight after the shutdown of Napster to get consumers to pay for something they could get free: music, then movies and videos. That's the genesis of iTunes.

Just before the scrubbing of SOPA and PIPA, the U.S. Government launched an international raid on Megaupload, an offshore site alleged to have caused about $500 million in damages to copyright holders and collected $175 million selling ads and premium subscriptions. The arrests triggered an attack on the Justice Department's Web site by Anonymous, which also cyberattacked the Motion Picture Association, Universal Music Group and others.

In its methods, Anonymous violates its First Amendment freedoms.

How will this dilemma be resolved? First, members of Congress will have to schedule a debate on Internet freedom. This may be egregious at times, although at least the late Sen. Ted Stevens (R-Ak.) won't be around to pontificate against the Internet as a series of tubes did in 2006.

An alternative bill, Online Enforcement and Protection of Digital Trade Act (OPEN) was introduced by two younger, more Web-savvy players, Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), 58, and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), 62, which would hand over dispute resolution to the U.S. International Trade Commission, the quasi-judicial agency which handles patent and dumping allegations.

OPEN enjoys some initial bipartisan sponsorship, backing of part of the technology sector, including the representatives from Silicon Valley, as well as the Consumer Electronics Association and Computer and Communications Industry Association.

In the 1971 Pentagon Papers case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 6 to 3 the Nixon Administration could not enjoin newspapers from publication, although the majority also ruled that there might be circumstances warranting censorship. That was the spirit of Ben Franklin, five years before Apple was even incorporated and only two years after the early Internet came about.

A little common sense and goodwill from all parties, mindful of the First Amendment, could easily resolve this issue. Is Mr. Franklin in the house?

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.