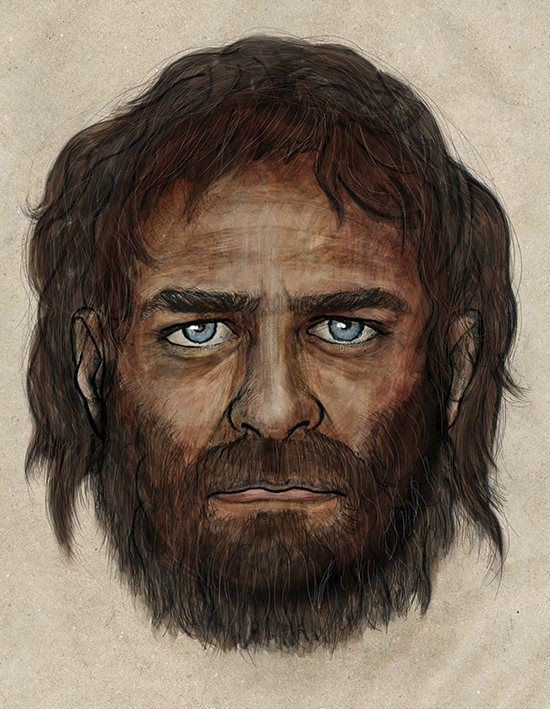

7,000-Year-Old Man Had Dark Skin And Blue Eyes; DNA From ‘La Braña 1’ Taken From Ancient Tooth [PHOTO]

The remains of a 7,000-year-old man have shed light on how ancient European hunter-gatherers may have looked.

Dubbed La Braña 1, the remains recovered at the La Braña-Arintero archeological site in Valdelugueros, Spain, included a wisdom tooth. DNA taken from the tooth suggests he had blue eyes, dark hair and dark skin. The findings, published in the journal Nature, also suggest that light skin developed not just because of Europe's relatively low-light conditions, but also due to hunter-gatherers' diet and environment.

"Before we started this work, I had some ideas of what we were going to find," Carles Lalueza-Fox, who led the study at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona, told the Guardian. "Most of those ideas turned out to be completely wrong."

Many scientists have supported the theory that lighter skin in Europeans developed approximately 40,000 years ago after humans migrated from tropical Africa. The latest discovery suggests this adaptation took longer than previously thought and instead occurred just 7,000 years ago.

"It was assumed that the lighter skin was something needed in high latitudes to synthesize vitamin D in places where UV light is lower than in the tropics," Lalueza-Fox told LiveScience.

Instead, the findings suggest that light skin was not wholly developed due to high latitudes, because that adaptation would have taken place thousands of years earlier, Lalueza-Fox said.

Besides skin color, the eye color suggested by the hunter-gatherer's DNA came as another surprise, since the mutation that causes blue eyes was thought to have developed earlier than the mutation that affects light skin color.

"Even more surprising was to find that he possessed the genetic variations that produce blue eyes in current Europeans, resulting in a unique phenotype in a genome that is otherwise clearly northern European," Lalueza-Fox said.

La Braña 1 was first discovered in 2006 when a group of cavers found two skeletons in the Cantabrian Mountains of northwest Spain. The cave’s cool environment preserved the remains of two men believed to be in their early thirties. Using the better-preserved of the two skeletons, scientists made several attempts before successfully reconstructing the man’s genome.

The researchers say their next attempt will be to perform the same task on the lesser-preserved skeleton, La Braña 2, in hopes of gaining a better understanding of early Europeans.

The findings also suggest that La Braña 1 may be a common ancestor of a 24,000-year-old boy found at Mal’ta near Lake Baikal in eastern Siberia. The boy’s DNA indicates he most likely had brown hair, brown eyes and freckled skin.

"These data indicate that there is genetic continuity in the populations of central and western Eurasia. In fact, these data are consistent with other archeological remains, similar to those found in excavations in Europe and Russia, including the site of Mal'ta, where anthropomorphic figures called Paleolithic Venus have been recovered, and they are very similar to each other," Lalueza-Fox says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.