Baby Star's Explosion Could Form Building Blocks Of Habitable Planets

A baby star's massive stellar flare was recently spotted by astronomers, who speculated that it may shed light on the secrets of the origins of potentially habitable exoplanets.

Scientists from the University of Warwick observed the huge explosion of energy and plasma, which they deemed to be one of the largest ever seen on a star of its type. The huge "tantrum" of the baby star was around 10,000 times larger than the biggest solar flare ever observed from our own Sun.

The astronomers, who published their findings in a paper for the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, found that this stellar flare could even unsettle the material orbiting a star. This, in turn, could create the building blocks for future planets.

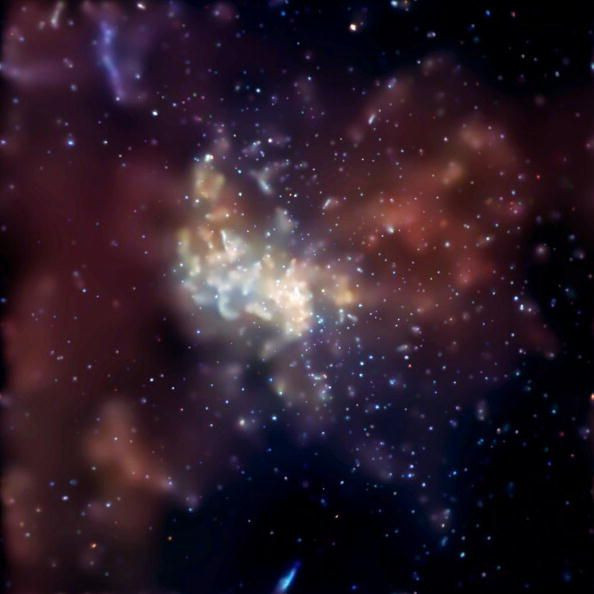

A stellar flare is a phenomenon wherein the magnetic field of a star rearranges itself and, in the process, releases large amounts of energy. This accelerates the plasma within the star, causing it to crash into its surface and heating it up to around 10,000 degrees. The energy produced from this releases optical and infra-red light, along with x-rays and gamma rays that can be observed using telescopes on Earth and in orbit.

This particular flare was seen on a young M-type star which was given the name NGTS J121939.5-355557 and is located 685 light-years away. It is only 2 million years, which means it is a pre-main sequence star and has yet to reach the size it will have for the majority of its lifecycle. The star could live up to tens of billions of years.

University of Warwick Ph.D. student James Jackman first spotted the baby star's explosion while he was observing a large flare survey of thousands of stars. This was part of a larger project aiming to find explosive phenomena on stars outside of our solar system. For the project, he used the Warwick-led Next-Generation Transit Survey (NGTS) telescope array at the European Southern Observatory's Paranal Observatory in Chile. This is designed to locate exoplanets by collecting brightness measurements of hundreds of thousands of star.

James' Ph.D. supervisor, Professor Peter Wheatley, said that stellar flares like this one could be advantageous for the formation of a planet, but it could also be disruptive, according to Phys.org. He added that the baby star has yet to form its planets, so its flare activity needs to be taken into account by astronomers when considering planet formation.

"There's a discussion at the moment around whether flares are a good or bad thing for life on orbiting habitable planets because they output a large amount of UV radiation," he said. "That could cause biological damage to surface organisms and damage their DNA. On the other hand, UV radiation is required for various chemical reactions to start life and that's not typically provided in great enough quantity by these types of stars. These flares could potentially kickstart these reactions."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.