BPA Free Plastic: Toxics Are Turned Into Safer Alternatives In New Green Discovery

Like dinosaur bones, the fossils of our modern era — CDs and DVDs — are often piled in forgotten heaps and buried underground. But these rounded relics are made of polycarbonates, a common plastic that decomposes in landfills and leaches toxic chemicals into groundwater.

Scientists in IBM Corp.’s research division have found a way to transform discarded CDs, smartphones, kitchen utensils and other polycarbonates into nontoxic plastics that can be used in water purification systems, medical devices and fiber optics. The recycled plastic won’t decompose and thus won’t leach bisphenol A (BPA), a synthetic compound that may disrupt brain development and cause other health problems.

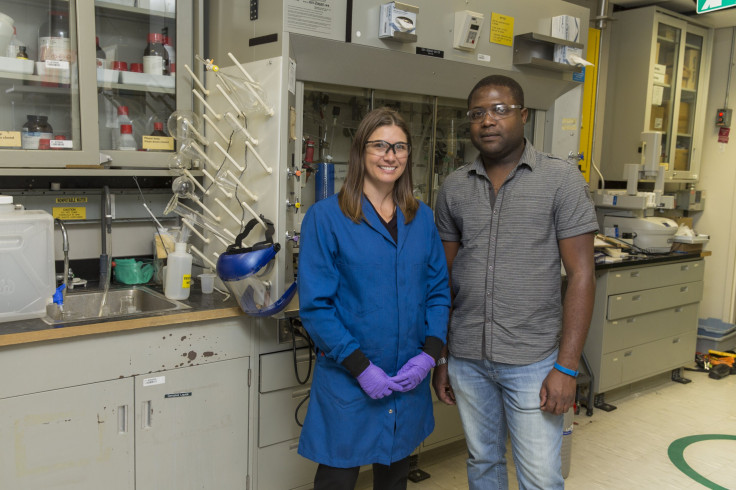

“We’re taking something that otherwise would be garbage and turning it into something that could be useful and help benefit the environment,” said Jamie Garcia, a researcher at IBM Research’s Almaden lab in California who developed the process with researcher Gavin Jones.

The recycling discovery, announced Monday, joins the growing universe of “green chemistry” — compounds and processes that aim to replace hazardous substances, reduce pollution in landfills and waterways and, in some cases, curb greenhouse gas emissions. While many of these solutions still exist only in labs or pilot projects, demand for greener alternatives is growing as consumers grow more wary of the chemicals in the products they use, wear and eat every day.

“There is a vibrant ecosystem of small innovators in the green chemistry space,” said Joel Tickner, director of the Green Chemistry and Commerce Council, a network of chemical makers, manufacturers, retailers and businesses that aim to make green mainstream. “As these companies grow, innovation will take root, and that might crowd out the chemicals people are concerned about.”

At the University of Delaware, for instance, chemical engineer Richard Wool has found a way to turn chicken feathers into computer chips. Keratin, a protein found in the feathers, was used to make a lighter, tougher circuit board that works at twice the speed of traditional circuit boards. Mango Materials, founded by Stanford University researchers, is transforming waste biogas (also known as methane) from a wastewater treatment plant into “biopolymers.” The startup is initially targeting microbeads — the ubiquitous spheres in cosmetic products — and other plastic products where biodegradability is a key concern.

The quest to create safer chemicals coincides with a broader push in the U.S. to tighten safety standards chemicals used in household and industrial products. President Barack Obama last week signed a law that will overhaul the 40-year-old Toxic Substances Control Act, giving the Environmental Protection Agency more leeway to review and regulate scores of chemicals. As authorities crack down on harmful substances, chemists and inventors are meanwhile creating a palette of safer alternatives.

The IBM researchers said that, at a larger scale, their recycling process could prevent a sizable slice of the 2.7 million tons of polycarbonate created each year from landing in landfills. Unlike the thinner plastic used in soda bottles and food containers, which are melted down and reused multiple times, polycarbonates are often not recycled because the process is expensive or complicated. CDs in particular contain aluminum, and sorting metal from plastic is an added barrier.

Garcia said their recycling discovery is a relatively simple process. At the IBM lab in San Jose, she first grabbed a stack of CDs left over by a group of interns. She picked a disc by one of her “least favorite late ’90s bands” and chopped it into half-centimeter pieces. Garcia put those chunks into a flask, weighed it and added a base similar to baking powder, a bit of solvent, heated the flask, and then dropped in a fluoride reactant. As the flask warmed, the CD pieces disappeared into a bubbling froth. Once cooled and filtered, the froth became a “beautiful pure white powder” — polysulfone, a thermoplastic polymer.

The new material is more chemically stable than polycarbonates and won’t decompose or leach BPA. So Garcia and Jones turned the powder into a reverse osmosis membrane, which is used in high-quality water purification systems. The researchers said they’re now hoping IBM can partner with a chemical company or another business to test and refine the process, reduce costs and scale it up to a larger level.

“It’s an environmental win on many fronts,” Garcia said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.