China Clears Way For Cloud Computing Industry In Himalayan Plateau, Despite Immense Obstacles

GUIYANG, CHINA — The promotional showroom for China’s data storage and analysis industry here combines a computerized other-worldliness straight out of Hollywood’s “The Matrix” with the hard-sell of Madison Avenue.

Sleek artwork outside the building plays on the phrases “cloud computing” and “Big Data.” Guides drop names of companies that have pitched their tents in Guizhou province, one of China’s poorest: Alibaba, Tencent, Foxconn. Disco-like lights project streams of numbers onto floors, fortifying the idea that a mighty river of data courses through the region.

And monitors blare forth with images of Chinese President Xi Jinping, who visited the area last year to endorse Guiyang’s bid to be the country’s hub for this business.

Today, it’s all a dream — a digital Potemkin village in eastern China.

China’s cloud-computing industry in Guizhou province stores a tiny fraction of the data handled by giants like Amazon. By the standards of its Asian neighbors, data crawls through China’s networks. The communist regime demands ready access to information of any type, dampening the enthusiasm of foreign investors who have financed much of China’s economic rise. Guizhou’s capital, Guiyang, is known for little more than its pleasantly crisp climate and a paint-strippingly strong sorghum liquor.

But this is China, which became a $10 trillion economic powerhouse in the space of a single generation by conjuring up new industries the way a magician pulls rabbits from a black top hat. Today’s dreams have a way of becoming tomorrow’s lucrative realities.

“If Guizhou can pull it off, it’s doable,” said Zhang Xinsheng, a longtime Chinese official who now heads Eco-Forum Global, an environmental group that promotes sustainable development.

Guizhou’s attempt to create a data storage and analysis industry from nothing is emblematic of the broader transformation of the Chinese economy that Xi needs to pull off to cement the Communist Party’s status as the institution guiding China’s renaissance. But Beijing, for all the party’s power, can’t will away the hurdles that make Guizhou’s transformation anything but a done deal, notably a dependence on infrastructure spending, the tendency of manufacturing to migrate toward cheap labor, and the head start that China’s coastal provinces enjoy.

China Focused On The Cloud

Guizhou’s top officials — backed to the hilt by Beijing — have set their sights on two buzzy phrases from the information technology lexicon: cloud computing and Big Data.

Cloud computing lets companies, governments and ordinary folk dispense with the local storage devices — whether rooms with servers or easy-to-damage hard drives — by replacing them with faraway server farms that harness economies of scale. It’s the computer-age equivalent of consolidating into mega-factories to cut costs.

Big Data tries to turn these huge pools of ones and zeroes into useful information with analytical tools that find the proverbial needle in the haystack. People who search their online files for a keyword are exploiting Big Data. So are companies who mine records to monitor customer preferences, employee habits and the performance of their latest widget, as are governments looking to detect problems in public services.

Rob Atkinson, founder and president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a Washington research group with close ties to the U.S. industry, said no competitor can afford to ignore the Chinese effort. Though China flaunts the western, market-oriented ideas that drive technological progress elsewhere, its sheer scale demands respect.

The cloud computing market in China was worth about $1.5 billion in 2013, according to the consultancy Bain & Co., and will hit $20 billion by 2020, a compound annual growth rate of 40 percent.

“Their ambitions are very high with regard to the technology, just as they are with virtually all information technologies,” Atkinson said. “It is only a matter of time before a large share of computing in China is done through the cloud.”

Guizhou is where the Beijing hopes cloud computing and Big Data, and the Chinese whizkids who are the brains behind it, find a Chinese home. And it’s where the money is.

Guiyang For The Money

Young Shu, 31, is a project manager at Longmaster, a modest-sized Guiyang-based company that started in 1998 as a phone messaging system, but now develops cloud-based systems for remote medical consultations, among myriad other business lines.

Longmaster’s main office, with hipster twentysomethings alternately scrolling through computer code and goofing off, is indistinguishable from Silicon Valley. What does set Guiyang apart: When Longmaster hires skilled developers who move there from elsewhere in China, they each can get up to $250,000 — about 20 times China’s per capita income — paid out over a few years as a moving bonus.

“A large portion of our talent comes from other areas because the weather here is good,” Young said with a smile.

The youthful hotshots who settle in the provincial capital even have a name in Chinese: the “guipiao,” a word that translates as “Guiyang drifters,” and evokes images of a leaf floating freely through the air.

Guiyang, the provincial capital, is draped over a series of hills, with many tunnels knitting the city of 4.5 million people together. The appearance of the countryside, though linked by new roads, would not surprise a peasant from a century ago, with its terraced rice paddies and intensive cultivation of every available surface. One-sixth of its people live on a little more than a dollar a day — a global measure for existential poverty.

Agriculture, coal mining, fertilizer production and traditional Chinese medicine production have formed the backbone of Guizhou’s economy for decades. Last year, Guizhou notched growth of 12.5 percent — about twice the rate of the country as a whole — as infrastructure spending helped it power ahead.

Thanks to pressure from Beijing to curb China’s property boom, residential and commercial construction has ebbed. But Guizhou’s workers are still building retaining walls, bus shelters, sewers, roads, parks and rest stops.

Humming with activity though it may be, China doesn’t have much to show so far for its investment in cloud computing.

The Great Firewall Isn't Helping

The Asia Cloud Computing Association, a trade group, ranked China’s readiness for a successful industry as 13th out of 14 countries in 2015. China is near the bottom in every meaningful respect, and actually dropped two spots from the previous year’s survey.

The report calls out slow broadband internet speeds. Data centers may be vulnerable to power outages or natural disasters. Intellectual property — the source code for the software that underpins Big Data innovation — is constantly at risk of theft or government-enforced expropriation in China.

Above all, the Chinese regime’s so-called Great Firewall of China will hold back China’s emergence as global powerhouse, the group concluded. “A commitment to ensuring the safe and free flow of data through China will be needed for it to become a leader in cloud readiness,” the group wrote in its report.

For all these weaknesses, however, China does have one notable and unique advantage in its desire to build a large-scale industry in Guizhou: The Communist Party wants the project. Period.

Xi’s visit last June, a typically scripted visit with the powerful Chinese leader giving his imprimatur to the Guiyang showroom, capped several years in which the government had no overall strategy.

China’s 13th Five-Year Plan, the document underpinning the country’s development strategy, took effect this year, and highlights data storage and analysis as two major priorities. Beijing branded the region China’s first pilot area for these industries.

Western companies like Amazon, Google or Microsoft had to convince ordinary people or large, international corporate clients to store data in the cloud, a process that took a while. But not in China.

The Five-Year Plan directs government agencies to hammer out plans to share data through the cloud by the end of 2017 and create a unified platform for storage of government data by the following year, creating vast pools of data that Chinese companies can use to harness the economies of scale offered by the cloud.

In Guizhou, Alibaba’s cloud subsidiary, Aliyun, already has a contract with the provincial government to manage its data. The city of Guiyang has a program up and running that uses a network of cameras to record traffic accidents, allowing municipal officials to monitor the honesty and professionalism of the police force.

Ditching Dirty Industries

Chen Shaorong, Guiyang’s executive vice mayor, describes this program as putting government agencies in “a data cage” — a tidy, if rather Orwellian, metaphor capturing the combination of business development and political control evinced by this particular application of cloud computing and Big Data.

With a confidence that would shock their counterparts in multiparty systems, Communist Party officials, enforcers of the official line, speak openly of abandoning entire industries to accommodate an information-based economy in Guizhou.

Shen Yiqin, the freshly installed deputy secretary of the provincial party, openly disdains the older businesses of Guizhou that, she points out, “burn a lot and pollute a lot” at a time when China needs less of both. “We will eventually get rid of these industries,” Shen said.

But as labor gets more expensive elsewhere, industry may yet migrate to Guizhou.

Gao Wenshu, an economist with the Institute of Population and Labor Economics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said Guizhou may very well experience “internal industrial reallocation” in which China’s workshops migrate away from the coast. Internal provinces in China have “a low proportion of manufacturing and they are populous,” Gao said.

Chen Shaorong, the executive vice mayor of Guiyang, said the city may be able to replicate the mass employment of manufacturing with businesses that are ancillary to cloud computing and Big Data. For example, the city is now home to about 100,000 seats for call center workers — that’s 200,000 individual jobs — who can get a piece of the action.

“We’re trying to see Big Data as a whole industry, not just the cloud computing servers,” Chen said.

Closing the gap with China’s prosperous southern and eastern provinces won’t be easy despite Guizhou’s torrid growth rates, said Nicholas Lardy, a China specialist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

“Though poor provinces grow more rapidly on average than the richer coastal provinces, the absolute gap between poor and rich is so large that the gap continues to expand,” Lardy said.

For example, per capita income in 2014 was 12,371 yuan — about $4,297 — per capita in Guizhou in 2014, China’s third-lowest. That figure is 10,329 in Guandong, the Chinese province that hugs the former British colony of Hong Kong, and China’s richest. In other words, Guizhou has to blaze ahead at more than twice the rate of Guandong simply to maintain the existing disparity.

Servers In Wind Tunnels

Guizhou has unquestionably birthed a small cloud computing and Big Data industry that may become the kernel of something bigger.

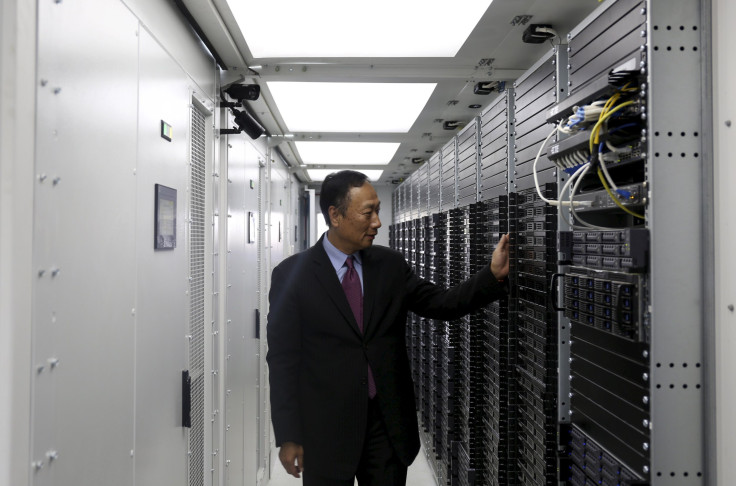

One piece of the embryonic industry lies on the outskirts of Guiyang where Foxconn, the Taiwanese contract manufacturer famous for assembling the iPhone, has set up inside hills over which the city has spread.

Over thousands of years, water eroded sedimentary rock like limestone to create the region’s landscape — ridges, small valleys, caves and other striking formations known as karst. Foxconn installed 12 massive sets of servers in a cave — effectively, a wind tunnel — that had already been bored through one hill. Since about 30 percent of the cost of a data center is energy for cooling, Foxconn was able to cut costs thanks to the already cool air that whooshes through naturally.

In January, Qualcomm, the American semiconductor designer, announced it would spend $280 million to set up a joint venture near Guiyang to develop and produce chips for computer servers in the Chinese market.

The investment grew out of a lengthy dispute Qualcomm had with the Chinese government, which charged the American company with violations of its antitrust law. Qualcomm settled the dispute by paying a $1 billion fine, and promising it would bring its own technology into the country.

China’s three largest mobile phone carriers — China Telecom, China Unicom and China Mobile — are already paying for cloud computing in Guizhou, giving the lines of Alibaba and Tencent access to an enormous market even discounting any foreign customers they might acquire.

Xu Yunzhou, a consultant to the Guiyang Industry and Information Technology Commission, a municipal body, estimates there are perhaps 50,000 servers already up and running in the city. By the standards of the United States or Europe, that doesn’t qualify as a drop in the bucket. But this is China, with its nearly 1.4 billion people, where the drops never seem to stop coming.

“This is a rough, dynamic figure,” Xu said. “Every day it is outdated.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.