Comet Plume Captured By ESA's Rosetta Spacecraft Powered From Beneath Surface

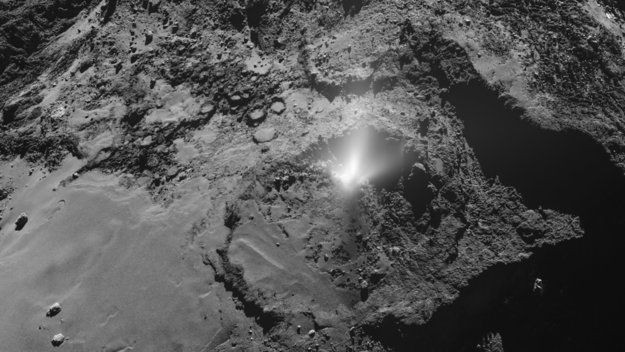

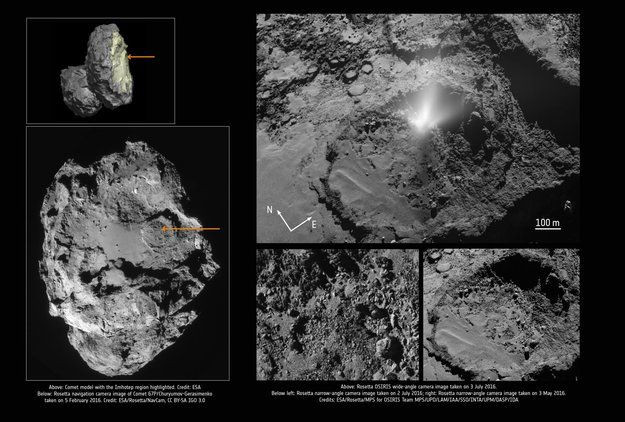

ESA’s Rosetta spotted a fountain of dust streaming from Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. This plume, which was spotted on July 3, 2016, was seen blowing from the surface of the comet for an hour as it was heading away from our sun at a distance of 500 million kilometers.

Since the discovery, there have been questions about the origins of the plume. The latest study by scientists from Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany, has suggested that the outburst was powered from inside the comet, perhaps released from ancient gas vents or pockets of hidden ice.

"We saw a bright plume of dust blowing away from the surface like a fountain," said Jessica Agarwal of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, and lead author of the new paper, in a report by ESA released on Oct. 26. "It lasted for roughly an hour, producing around 18 kg of dust every second," she added.

The spacecraft also captured a steep increase in the number of dust particles flowing from the comet, the report said. The image also captured grains of water-ice in the plume which happened at a place on the comet with a 10 meter-high wall around a circular dip in the surface.

"This plume was really special. We have great data from five different instruments on how the surface changed and on the ejected material because Rosetta was, by chance, flying through the plume and looking at the right part of the surface when it happened," said Jessica in the report. "Rosetta hasn’t provided such detailed and comprehensive coverage of an event like this before," she added.

Initial claims said that the plume is just surface ice evaporating because of sunlight. However, data collected by Rosetta showed the team that there had to be something more energetic going on to fling that amount of dust into space for one whole hour.

"Energy must have been released from beneath the surface to power it," says Jessica. "There are evidently processes in comets that we do not yet fully understand."

The presence of this energy remains unclear. The team can just speculate on what caused the energy build-up that caused the plume. They have several theories which range from pressurized gas bubbles rising through underground cavities and bursting free via ancient vents to stores of ice reacting violently when exposed to sunlight.

"One of Rosetta’s major goals was to understand how a comet works. For example, how does its gaseous envelope form and change over time?" said Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist in the report. "Outbursts are interesting because of this, but we weren’t able to predict when or where they would occur — we had to be lucky to capture them," he added.

The team members are now using the multi-instrument coverage of the outburst to try and reveal how these events occur. The data from Rosetta is used along with computer simulations and laboratory work to find out what drives such plumes on comets.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.