Global Deflation On The Rise? World Economy Threatened by Financial Slowdown

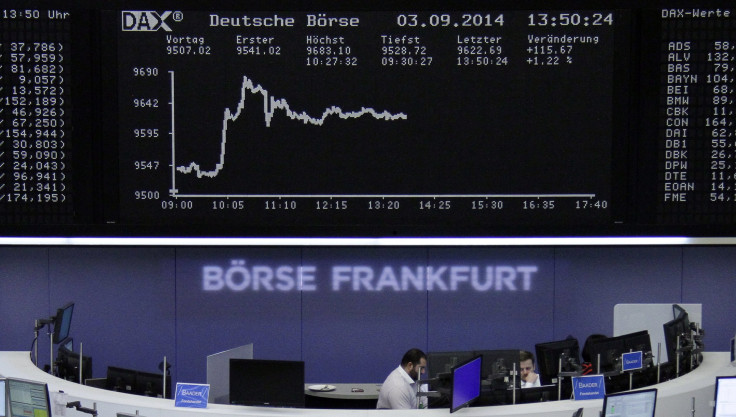

A global economic slowdown has raised the threat of deflation amid sluggish growth, falling commodities prices and tumbling stocks. The gloomy fiscal outlook could translate to less economic momentum as consumers and businesses grow more cautious.

Deflation is a four-letter word in finance, largely because it is so difficult to recover from. Japan, the most cited example, withered under deflation for two decades before it rebounded. With a drop in global oil prices, weakening bank credit and depressed manufacturing activity, nearly all signs suggest the global financial system is heading in that direction even as world leaders have fought to emerge from the 2009 global recession that wiped out years of economic growth.

Just how imminent the threat is depends on what steps world leaders take over the coming months to massage consumer trends and other factors in their favor. Inaction is not an option, financial leaders said.

"Global growth is a bit weaker than we expected, mostly because potential growth in emerging markets is lower, but also because Europe is not taking off. Growth being weak in Europe is a more worrisome thing because it is basically suggesting that the Europeans are not willing to put in place the right policies to solve their problems," said Angel Ubide, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, D.C., and a former economist at the International Monetary Fund. "I have a feeling a lot of people are thinking that we have a problem that can’t be solved."

The markets are far from facing the kind of massive deflation that accompanied the Great Depression decades ago. But a lesser crisis would still ripple through the global financial system. Analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch said in a recent note to clients that the markets have started to brace for another recession or the collapse of a major market player.

"If we don’t take the bull by the horns we are going to be in trouble and we needn’t be," said Ernesto Talvi, director of the Brookings Global-CERES Economic and Social Policy in Latin America Initiative. "We learned a lot from the Great Depression, and we know much better how to prevent that and actually we did ... but it could be a major slowdown and a durable one."

In China, the world's second-biggest economy, prices rose by 1.6 percent in September. Inflation in India has dropped to 2.38 percent from 10 percent less than a year ago. The U.S. is grappling with 1.7 percent inflation. Europe faces a particularly difficult economic climb, with inflation slowed to 1.2 percent in the United Kingdom, the ninth month it has dropped below the Bank of England's 2 percent inflation target, according to the BBC News. In the 18 nations that use the euro, annual inflation was 0.3 percent last month, far below the European Central Bank’s target of just under 2 percent. Japan and Brazil also are struggling with stagnant economies.

Global inflation has declined because of weak growth, debt repayment and falling commodity prices. At the same time, central banks and other policymakers have been unable to tackle global deflationary forces, signaling the global slowdown will be hard to shake off.

"We know what needs to be done, but I don’t think it is very likely to be done," Ubide said.

To ward off deflation, the European Central Bank has begun injecting cash in exchange for buying asset-backed securities, while China has eased credit conditions. Analysts say further policy changes are required to make a real difference, including slashing interest rates, reducing borrowing costs and buying government assets, such as bonds. However, the necessary fiscal, monetary and structural reforms have been slow to come, particularly within the European Union, where member states such as Germany and France have conflicting needs.

"The broad risks of missing your inflation target are only part of the story in Europe. The real concerns are lingering concerns over employment and growth and the lack of structural reforms," said Douglas Rediker, a visiting fellow at the Peterson Institute who represented the U.S. on the executive board of the International Monetary Fund from 2010 to 2012. "It is far from clear how to address this because steps taken from the central bank are inevitably going to impact some countries differently than others. Countries like France, Italy and others need to embrace structural reforms and adhere to financial management out of Brussels."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.