McStay Family Murders: New Arrest Exonerates Mexican Drug Cartels, But Thousands Still Missing In Drug War Violence

One year after the remains of the McStay family were found buried in a Southern California desert, authorities this week arrested Charles "Chase" Merritt, a business associate of the father, Joseph McStay, in their deaths, officials announced Friday. Merritt has been charged with four counts of murder, accused of killing Joseph McStay, his wife Summer McStay, and their two children, 4-year-old Gianni and 3-year-old Joseph Jr., sometime shortly after the family vanished four years ago. Authorities hope the development will finally help investigators put the case to rest.

The circumstances surrounding the bizarre disappearance of the McStay family, who went missing in 2010 from their home in Fallbrook, north of San Diego, have largely remained a mystery. Some questioned whether Mexico’s violent drug cartels, which began all-out war in 2006 and have killed tens of thousands of people across Baja California and neighboring Mexican states, were somehow involved after the family’s SUV was discovered in a parking lot in San Ysidro near the border, an hour from their home. The Mexican cartel theory was eventually abandoned after the remains of the four were uncovered by a motorcyclist on Nov. 11, 2013, near Victorville, northeast of Los Angeles.

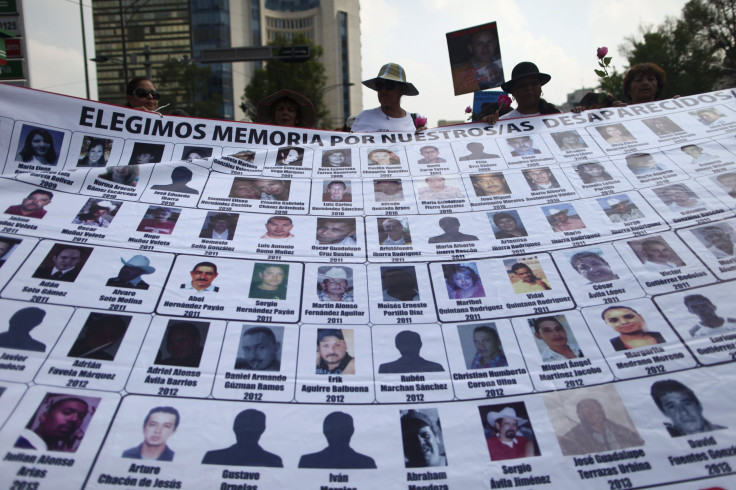

While the discovery apparently exonerated the cartels in the McStay family’s murders, it did not absolve Mexico’s notorious drug gangs for the tens of thousands of deaths and disappearances that have occurred over the past eight years. More than 26,000 adults and children have vanished in Mexico since the chaos and violence erupted in 2006, according to Mexico’s attorney general. Thousands more have been ruthlessly killed.

Accurate tallies of the number of Mexicans who have died in drug-related violence are difficult to procure. Statistics from local authorities are often unreliable, and crimes in Mexico are thought to be vastly underreported. The official death toll of the Mexican drug war at the end of President Felipe Calderon’s presidency in 2012 was at least 60,000, according to the Washington Post. Outside groups have put the estimates much higher.

The Trans-Border Institute of the University of San Diego, which tracks Mexico’s homicide rates, estimated there were between 120,000 and 125,000 murders between 2006 and 2012. Exactly how many were related to drug violence was unclear, but subsequent research on the number of drug violence-related deaths in Mexico has produced similar figures.

"The overwhelming majority of the deaths are people shot down on the street, in their homes or workplaces, on playgrounds, etc.,” Molly Molloy, a research librarian and border specialist at the New Mexico State University Reference and Research Services in Las Cruces, wrote in a study published in August 2013. “In my reading of the daily accounts of the killings, it is clear that most of the victims are ordinary people, exhibiting nothing to indicate they are employed in the lucrative drug business,” she noted.

Police corruption is another cause of unexplained disappearances in Mexico. In October, 43 students went missing after confrontations with local authorities erupted there. Investigators believed corrupt police had kidnapped them and handed them over to the local gang, the New York Times reported.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.