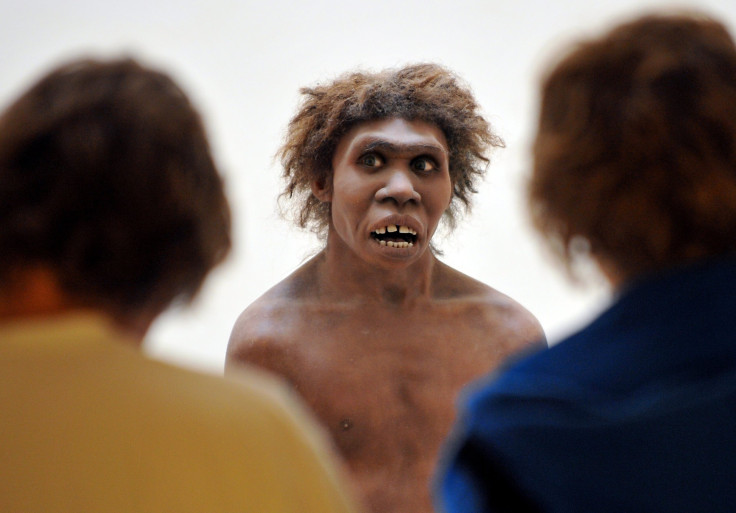

Neanderthal DNA Reveals Human Evolution Timeline Through Genetic Mutations

There may have been a lot more Neanderthals roaming prehistoric Earth than scientists have previously thought, DNA shows.

A statistical analysis looked back into the human evolution timeline, studying genetic mutations over the last several hundred thousand years to find that the Neanderthals and another cousin of modern humans, the Denisovans, almost went extinct shortly after diverging from the evolutionary tree branch that birthed us before the Neanderthals saw a boom in population. A study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences says that the researchers’ analysis also further backs up the idea that our ancestors had sex and interbred with the Neanderthals.

Read: Prehistoric Humans Had A Lot of Sex With Neanderthals

When it comes to population size, “these results contradict current views about Neanderthal population history,” the study notes, because estimates have suggested there weren’t a lot of them — perhaps a thousand.

That’s in part based on the number of negative genetic mutations found in their DNA. In a large population, evolution gradually weeds out harmful genetic mutations but smaller populations do not have enough clean genetic material to achieve that.

The new statistical analysis, however, suggests there were tens of thousands of Neanderthals.

“To reconcile these views, we suggest that the Neanderthal population consisted of many small subpopulations, which exchanged mates only rarely,” the authors wrote. “In such a population, the effective size of the global population can be large, even if each local population is small.”

Those small communities of Neanderthals could have had potentially harmful genetic mutations proliferating through their group, a telltale sign of a species going through a decline leading to extinction, even while the global population was still large.

“The idea is that there are these small, geographically isolated populations, like islands, that sometimes interact, but it’s a pain to move from island to island,” co-author Ryan Bohlender, from the University of Texas, said in a statement on the research from the University of Utah. “So, they tend to stay with their own populations.”

The setup would also explain wide genetic differences between Neanderthals and the fact that they were so widespread geographically, with evidence of their existence turning up all over Eurasia.

The Neanderthals had their population boom after diverging from the Denisovans almost 750,000 years ago, only a few hundred generations after they diverged from the modern human line, according to the research. That is earlier than previous estimates.

The statistical analysis relied on estimates of the amount of genetic material flowing between ancient humans, and those estimates come from tracking genetic mutations through history to see where they have originated and what other populations share them. They were comparing the genomes of Neanderthals, Denisovans and modern Africans and Eurasians.

Read: This Skull Fossil Is Part Human, Part Neanderthal

“You’re trying to find a fingerprint of these ancient humans in other populations,” lead study author Alan Rogers said in the statement. “It’s a small percentage of the genome, but it’s there.”

Finding fewer mutations in common between Neanderthals and Denisovans was a clue that their branch of the evolutionary tree split earlier.

“This hypothesis is against conventional wisdom, but it makes more sense than the conventional wisdom,” Rogers said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.