Ebola Outbreak 2014: How Researchers Use Big Data To Help Stop The Disease

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa is the largest ever recorded.To date there have been more than 5,800 cases and 2,800 deaths recorded by the World Health Organization (WHO). The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has predicted that it could affect 1.4 million people. Before this, the largest Ebola outbreak killed 425 people in Uganda more than a decade ago.

But today, health workers are using a resource they didn’t have back then.

“Big data has really changed epidemiology,” Madhav Marathe, director of Virginia Bioinformatics Institute’s Network Dynamics and Simulation Science Laboratory, said to International Business Times.

His team has been working with the U.S. Department of Defense for nine years to help track diseases like Ebola and H5N1 and create models to predict how they might spread. Recently, they’ve started using data from cellphones and social media in addition to more traditional methods.

“There have been some very interesting new developments that can have a huge impact,” he said, explaining that researchers are now using new sources like cellphone data or social media postings to help them track and fight the deadly virus. “You take all this data and build this virtual city and it allows us to synthesize and fuse multiple data sources to run large-scale simulations.”

Caitlin Rivers, one of his Marathe’s team members, has been compiling and analyzing data as part of a new project called “#HackEbola,” in which she digitizes the data put out by local ministries of health and publishes the results online.

The recent outbreak has only emphasized how weak health systems are in the affected countries. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to 1 percent of the world’s population but bears 24 percent of its global disease burden, according to the WHO. Before the outbreak, Liberia had just one doctor for every 70,000 people, while Sierra Leone one for every 45,000. At the same time, mobile data use has been growing exponentially and is on track to hit 930 million users by the end of 2019, up from 551 million at the end of last year. For doctors fighting Ebola, this is more than an interesting trend -- it’s a valuable resource.

“If it were happening in the U.S. we’d have a lot of databases for health care and electronic records, but those things don’t exist in the same way over there,” Laura Forsberg White, associate professor of biostatistics at Boston University, told IBtimes. “There is a lot of interest and people feel optimistic that there is a lot we can gain from this that we can’t gain from our traditional data sources.”

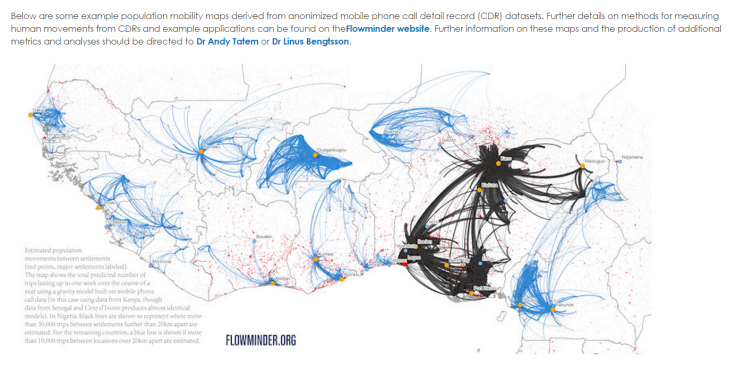

Caroline Buckee, associate director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at Harvard’s School of Public Health, has spent the last few years using cellphone data to help track diseases.

“They are particularly useful sources of data in settings where we don’t have other information,” Caroline Buckee, assistant professor of epidemiology at Harvard School of Public Health, told IBTimes. She and her team have been working with local cellphone providers, who are able to give them data from cellphone users that helps track movement. “This approach could be useful almost anywhere there are people and phones.”

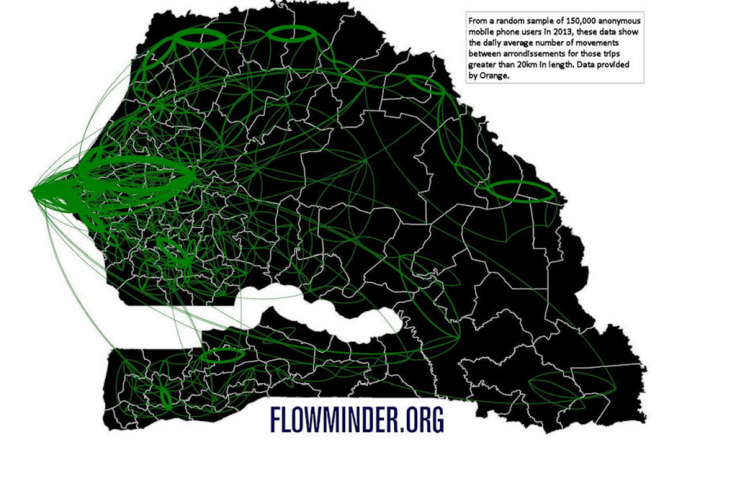

Basically, whenever a person makes a call, the call is routed through the nearest cellphone tower, which can give an approximate location.

“You can build up a picture of where the person is over time, and count the transitions between different towers,” Buckee said, adding that all cellphone providers “anonymize” their data, which means that researchers can analyze how people are moving, without knowing anything else about them, which addresses privacy issues.

Buckee recently joined the board of Flowminder, a Stockholm-based organization that uses cellphone data to help NGOs and government agencies tackle large-scale public health problems that come from natural disasters or disease outbreaks.

Unlike malaria, Ebola is transmitted by human contact, which means knowing when and how people are moving around can provide incredible insight to researchers trying to stem the outbreak.

But it’s not just cellphone movement that’s helping researchers, it’s also what people are using their phones for.

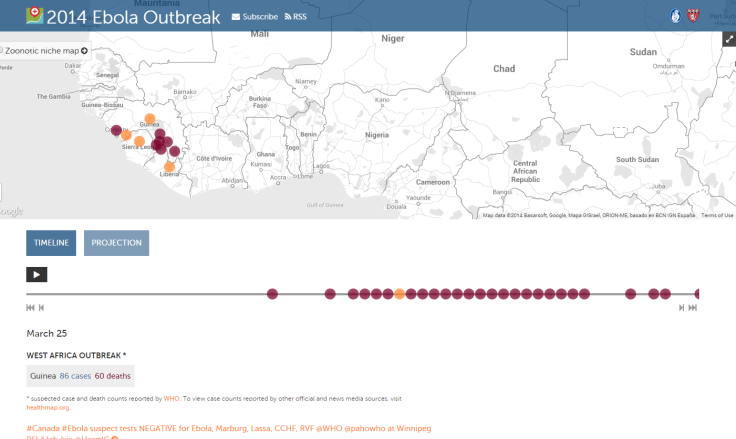

HealthMaps is another online platform that combs the Internet to track and predict diseases around the world. Nine days before the WHO announced the outbreak in Guinea on March 23, a team of researchers thousands of miles away already knew about it, because their software had picked up a local news report of “une étrange fièvre,” (a strange fever) in the Guinean town of Macenta on March 14.

“We allow anyone, anywhere in the world to submit a direct report of an outbreak event,” HealthMaps co-founder Clark Freifeld said in a recent interview with Fast Company, adding that the more people become connected, the more possibilities are opened up.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.