Thursday Books Blog Report: Will Paper Books Go Extinct?

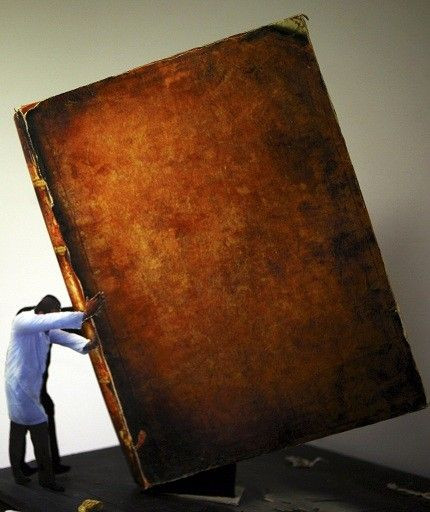

As e-books ascend in the years to come, what will be done with our paper books? What should be done with them?

Michael Montoure delves into that issue today, saying he does not think paper books will go extinct.

Sure, the majority of books will be in digital form, but I think paper books will continue to exist as a specialized collector's commodity, he writes.

He then gets into a conversation of sorts with Kevin Kelly's recent article on The Technium titled When Hard Books Disappear. Montoure says Kelly lays things out in one hell of an evocative paragraph. Here it is:

We are in a special moment that will not last beyond the end of this century: Paper books are plentiful. They are cheap and everywhere, from airports to drug stores to libraries to bookstores to the shelves of millions of homes. There has never been a better time to be a lover of paper books. But very rapidly the production of paper books will essentially cease, and the collections in homes will dwindle, and even local libraries will not be supported to house books -- particularly popular titles. Rare books will collect in a few rare book libraries, and for the most part common paper books archives will become uncommon. It seems hard to believe now, but within a few generations, seeing an actual paper book will be as rare for most people as seeing an actual lion.

So we are living (possibly) at the apex of the printed book -- and our grandkids won't get to see lions or hold books in their hands.

But the Technium piece gets even more interesting, as Kelly describes how one man -- Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle -- has recently undertaken a new cause, keeping a physical archive of books that are digitized.

Kahle noticed that Google and Amazon and other countries scanning books would cut non-rare books open to scan them, or toss them out after scanning, Kelly writes. He felt this destruction was dangerous for the culture.

So Kahle decided that he should keep a copy of every book they scan so that somewhere in the world there was at least one physical copy to represent the millions of digital copies. That safeguarded random book would become the type specimen of that work, Kelly writes.

He is storing the books -- as well as digital version of them, for the day that they will inevitably be rescanned -- in a metal warehouse in Richmond, California, which Kelly visited recently.

The big idea that EVERY digital form ultimately rests in a physical form is a deep truth that needs to be understood more widely, Kelly emphasizes. It's worth taking some time to consider that.

Kelly concludes by noting that only the Internet Archive is making broadly available backups of the Internet, television and radio broadcasts, and the backups of books. Someday we'll realize the precocious wisdom of it all and Brewster Kahle will be seen as a hero.

'Someday?' Montoure responds. Hell, I think he's a hero now.

In a recent post that also takes Kelly's Technium piece as its jumping-off point, BW Brooks says he thinks books are a long way from disappearing, but he strongly supports storing the body of human knowledge.

Kahle's effort will preserve something of the world as we know it. And for all those who complain about the ephemeral nature of eBooks and the online world, it provides a measuring stick against which to measure drift, he writes at Postcards and Portmanfaux.

Brooks' question: what is a pure book for preservation purposes? He lists some possibilities -- check them out in his post.

Elsewhere in the books blogosphere today, Arline Chase asks why e-books are selling so well of a sudden, after e-readers have been around for a decade.

Her answer: The newer reading devices are MUCH less clumsy to use and easier to see than the older ones.

My first e-book cost $380, had a 2-inch screen, with liquid crystal display of black against dark gray, and was invisible altogether in strong light, with a battery life of about two hours. In addition, to buy a book, I had first to download it to my computer, then go through several steps to load it into the e-book for reading, Chase writes, adding that the reader's memory was also very short.

In contrast, her Kindle cost less than half as much, works anywhere a cell phone works, takes me straight to the online store for selection and downloads the chosen book right then and there. Takes less than a minute to get it, if I know what I want. I read a LOT and the battery life lasts 20 hours or so -- for me half a week.

Referencing Marshall McLuhan, Chase says that reading is the hottest medium because it happens inside your head and is participatory -- you create what you see with your imagination, whereas with movies or TV you absorb the story, and there are distractions that remind you that you are in the real world.

Reading gives the reader more satisfaction than any other pursuit, except maybe sex. Well, good sex. Because it allows you to escape the world around you, and become one with the written word, Chase says. This is why, whatever technology may give us, the act of reading will always be popular.

On that note, Barnes & Noble wants to give you lots of e-books -- if you switch to a Nook.

The country's largest bookstore retailer began promoting today a deal in which you can get 30 free digital titles worth $315 if you go into a Barnes & Noble with any e-reader and upgrade to a Nook. The offer takes effect July 1.

Says Quentyn Kennemer at phandroid.com, If you needed a good reason to jump into the NOOK bandwagon, this may be it.

Edward B. Colby is the Books editor of the International Business Times. He can be reached at e.colby@ibtimes.com.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.