What are Flash Mobs?

ANALYSIS

For the Rugby World Cup in New Zealand, a group of Maori men have been gathering in public places and randomly breaking into the Haka, a traditional war-dance and the intimidating warm-up of the country's national team.

The spontaneous dance could be considered a flash mob.

Last month in the U.S., a group of teenagers ransacked a Dallas convenience store, stealing as much as they could carry and viciously attacking a store clerk.

That too, could be considered a flash mob.

Flash mobs are becoming an increasingly common phenomenon in many cities around the globe. Generally organized through technological means -- either on social media networks like Facebook and Twitter, or through text message or email -- flash mobs see groups of people instantly gather in a specific location, sometimes for malevolent reasons.

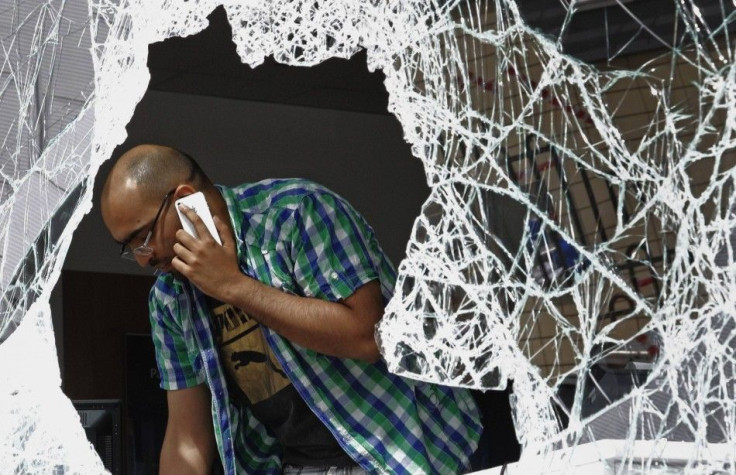

To a bystander, flash mobs appear suddenly and without warning. They often can be violent, terrifying. This trend is especially true in the U.S., and recently there have been flash mobs in Washington, D.C, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin and Iowa, where gangs of kids have attacked innocent people in the street, robbed stores and damaged property.

In July, about 30 teenagers congregated near Philadelphia's City Hall and severely beat two people, leaving one unconscious and the other needing surgery for a broken jaw. In June, some gangs attacked pedestrians and people leaving restaurants, while others robbed train passengers. Still others walked into stores and businesses and walked out with stolen goods.

These events are random and seemingly pointless, organized simply because people can get away with them.

Yet, peaceful flash mobs are equally common. They are sometimes done as a form of nonviolent protest, like in Chile, where students have gathered at the presidential palace to dance to Michael Jackson's Thriller to show their disapproval of the country's rotten and dead education system.

Other flash mobs are simply done for fun, with dances in malls, people moving in slow motion inside a Home Depot, or 3,000 people suddenly freezing on the streets of Paris.

Generally, the biggest flash mobs are demonstrations of public will, not of public violence, but there are always exceptions to the rule.

Both the London riots in August and the Egyptian protests in Tahrir earlier this year that led to the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak can be thought of as flash mobs, because they used technology as a tool of rapid organization.

Iran's Green Revolution in 2009 was called the Twitter Revolution at the time. Thousands of people gathered in cities in Iran in defiance of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who won his reelection in a vote that was widely considered to be fraudulent. Protestors used Twitter, as well as other social-networking sites, to communicate with each other, and with the Iranian diaspora around the world.

Ahmadinejad's government temporarily shut down the Internet, as well as blocked sites like Facebook, YouTube and certain media outlets, but young Iranians tweeted lists of Web proxy servers, helping each other get by the restrictions.

This summer, Iranian youth have again turned to the flash mob to protest the puritanical regime. In July and August, men and women congregated in Tehran for large water gun fights. As harmless as that sounds, dozens of people were arrested for acts against religion and disrupting public security.

It's easy to credit (or blame, depending on the side one supports) technology for the demonstrations, but social media is only a tool, not a cause. While flash mobs, in their current iteration, may not have existed in a pre-Internet era, there have always been uprisings, as well as gangs, civic unrest and unexplained brutality.

Some politicians -- including some in the U.S., like the Cleveland city council, which voted unanimously to ban the use of social media or cell phones to start a flash mob -- believe that banning the use of social networks to organize demonstrations will stop future demonstrations, but that is a naive and dangerous assumption. Not only does criminalizing technology not get to the root of the problem, but it'll also do little to deter youths. More importantly, restricting the rights of citizens will only make them more likely to lash out, as was evident in Egypt and Iran.

As the ease of communication increases and networking platforms become more widespread, the flash mob trend will get more intense before it begins to lessen. This trend will eventually be curbed, but fighting the technology isn't the means to an end.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.