95 New Exoplanets Discovered, Thanks To Kepler’s K2 Mission

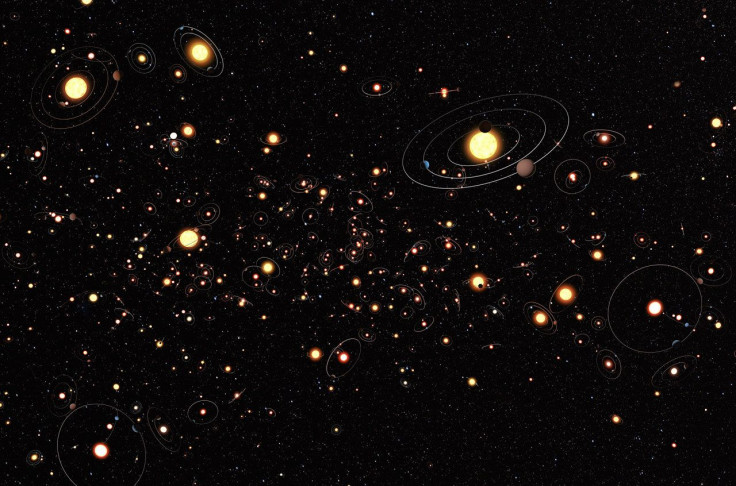

There are 95 additions to the ever-growing list of exoplanets, as researchers analyzing data collected by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope discovered them scattered around our home galaxy, the Milky Way. About 3,600 exoplanets are known to exist outside our solar system now, most of them thanks to Kepler. Some planets have also been discovered recently outside the Milky Way.

An international team of researchers made the discovery while analyzing 275 potential exoplanet candidates that showed up in the Kepler data during the spacecraft’s second mission, called K2. In 2013, four years after its launch, there was a malfunction in Kepler that ended its first mission. But a repair was affected in 2014, and the second phase of its planet-hunting mission, which is still ongoing, was called K2.

Of the 275 candidates in the dataset — being compiled since the first K2 data release in 2014 — 149 were verified to be actual exoplanets, and of those, researchers found 54 had already been discovered earlier, leaving them with 95 previously unknown exoplanets.

“We found that some of the signals were caused by multiple star systems or noise from the spacecraft. But we also detected planets that range from sub Earth-sized to the size of Jupiter and larger,” Andrew Mayo, a Ph.D. student of the National Space Institute (DTU Space) at the Technical University of Denmark, who was lead author of the paper announcing the discovery, said in a statement Thursday.

Kepler finds exoplanets by looking for dips in the light from a star as a planet passes across its face during its orbit. But since the dips in light can have other causes too, all such candidates identified by Kepler need to be tested using other means to validate whether they are in fact exoplanets or something else. One of the new 95 discoveries was somewhat special.

“We validated a planet on a 10 day orbit around a star called HD 212657, which is now the brightest star found by either the Kepler or K2 missions to host a validated planet. Planets around bright stars are important because astronomers can learn a lot about them from ground-based observatories,” Mayo said.

Exoplanets were once thought to be rare, but it is general scientific consensus now that planets exist in the trillions all over the universe. Recently, the first discovery of planets outside the Milky Way was made in a galaxy about 3.8 billion light-years away.

Just like the planets in the solar system range in size from the tiny Mercury (18 of it could fit inside Earth) to the gigantic Jupiter (about 1,300 Earths could fit inside it), exoplanets come in a variety of sizes and masses too — some smaller than the moon and others a few times larger than Jupiter.

While thousands of exoplanets are already known, and there are thousands of other candidates, we still know precious little about what those worlds are like. The upcoming launches of missions like NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite should further our understanding.

The research will be published in the Astronomical Journal, and is currently available on the DTU Space website.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.