Blue State/Red District: Pro-Trump House Votes Could Haunt Heartland Incumbent Jeff Denham

This story is being co-published with Capital & Main

Last January I stopped by a classic car show in the spacious parking lot of a Modesto Pep Boys store as the second annual Women’s March passed by on McHenry Avenue. Despite the men and women marching just feet away, people at the car show offered few answers as to which issues might be animating the local red-blue divide — or why Republican Congressman Jeff Denham, who represents California Congressional District 10 here, has been bucking the district’s decidedly blue-ish voting pattern for the past eight years. Since Donald Trump took office, Denham has voted with the president nearly 99 percent of the time, though he represents a district where Hillary Clinton beat Trump by three percentage points in the 2016 election.

Some responses suggested that voters here are politically disengaged. On the polite end, one woman told me she didn’t follow politics because it was all so negative. On the less polite end one man told me to “get outta here with that politics crap.”But the more people I met in CA-10, the more specific opinions I heard about the direction of the district, if not about this year's political candidates. More than one person mentioned the growing homeless population, which is concentrated downtown, and whose members are often casualties in the one-sided war of rising rents. People also worry that Modesto is becoming a far-flung bedroom suburb for people working at high-paying jobs in the San Francisco Bay Area – but not high-paying enough to afford to live there -- and who don’t mind commuting four hours-plus daily. One 24-year-old man said he commutes to a restaurant waiter job in San Jose because it pays far more than anywhere in Modesto.

Congressional District 10 contains all of Stanislaus County, part of San Joaquin County and spans the fertile northern San Joaquin Valley, also known as “the northern valley.” The land between towns hasn’t been bulldozed for development, at least not yet. Amid the constellation of small cities – Turlock, Patterson, Ripon, Manteca -- there are the same almond, peach and walnut orchards and ranches that have existed for generations. "Pray for Rain," urges a prominent sign in one orchard off the 99.

The largest city, Modesto, has just over 200,000 residents. Big-box retailers and plentiful Starbucks make sections of Modesto resemble Southern California’s megalopolis. One resident quipped that his city is “90 minutes from everywhere you’d rather be.” Another man complained that a trip across Modesto, which used to take 20 minutes now takes 30. But nobody I spoke with expressed a desire to move away. Houses in Stanislaus County are less than half the price of those in the Bay Area's Alameda County, according to RealtyTrac.

Some metrics underlie unease in the district. The median income for CA-10 is just under $50,000, far less than the California median, which was $67,739 in 2016. The unemployment rate for San Joaquin County was 6.6 percent in December. For Stanislaus County it was 6.8 percent in December. Both are well above the statewide rate of 4.2 percent. The high school graduation rate is just over 77 percent for the district, but the college graduation rate is 17.6 percent. In one of its less auspicious statistics, Modesto sported one of the highest rates of vehicle theft in the U.S. in 2016.

None of these figures illuminated the reason Denham why supporters I met with tended to be single-issue voters (“he’s pro-military”), while Denham detractors often said his voting record didn't match his rhetoric, and many of them cited immigration reform and health care as their core issues.

Sitting Out The War On Smog

None of the people I spoke with cited the environment as a top voting issue, though they did say that the influx of commuters to the Bay Area was probably worsening the air quality. And the air quality in CA-10 is already pretty bad. The Modesto-Merced area, which Denham represents, has the fourth-worst short-term particle pollution in the country, and suffers the sixth-worst long-term particle pollution nationwide. Modesto-Merced also has the sixth-worst ozone pollution in the U.S., with an estimated 16,164 current cases of pediatric asthma. Stanislaus County, which accounts for most of CA-10, ranks number four in highest short-term particle pollution levels of all counties in the U.S.

Denham has drawn fire for his support, in the House, of the Ozone Standards Implementation Act, dubbed the “Smoggy Skies Act” by critics for its proposed weakening of both ozone limits and the Clean Air Act. One of the most controversial elements of the legislation is a provision that would compel the Environmental Protection Agency to take into account factors other than public health in establishing pollution standards. Among those factors is the financial burden on business.

In 2016, the oil and gas industry donated $188,999 to Denham’s campaign. During his time in Congress, Denham has received $421,250 from Big Oil. In addition, he has received $229,050 in contributions from the trucking industry and $250,250 from the railroads, both of which rely heavily on diesel engines that emit ozone and particulate matter. All in all, he has collected more than $900,000 from industries that stand to benefit most from the gutting of the Clean Air Act.

First, Do No Harm

In early 2017, acasignups.net estimated that 15 percent of Affordable Care Act (ACA) enrollees in CA-10 could lose coverage if a Republican repeal-and-replace plan, such as the American Health Care Act (ACHA), were to pass. During the Obama administration, Denham voted with his party to repeal the ACA (also called "Obamacare") several times. Under Trump, he promised constituents that he would repeal ACA only if it were replaced with a law he considered better. But in early May, Denham voted for the ACHA, even though the bill had a 33 percent approval rate in CA-10.

Denham has a long history of voting against popular health-care legislation. As a member of the California Legislature, he opposed numerous bills that were ultimately passed by both chambers and signed into law by Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Denham voted against domestic partner coverage, protections for elderly members of continuing care facilities, enhanced consumer protection for denial of coverage, prohibition of smoking in cars with minors and required coverage of HIV testing, among other health-care bills. He also opposed the law that created the California Health Benefit Exchange, the agency charged with implementing the Affordable Care Act. During his time in the Legislature, Denham received extensive financial support from health-care insurance companies and providers.

Yamilet Valladolid manages a community health clinic in a rural section of Stanislaus County. Nothing lies between the clinic and Modesto's hospitals but 25 miles of orchards.

Valladolid's clinic offers general health care -- for specialized treatment and dental care, patients must go to Modesto, an hour-long bus trip away. “There is a critical physician shortage here in Stanislaus County," said Valladolid. "We’re not the Bay Area.”

There are many Medi-Cal patients at Valladolid’s clinic, which also offers a sliding fee scale for other payers. She said her patients, who are primarily Latino and low-income, often suffer from diabetes and high blood pressure. “Many of the rural communities here have seasonal workers, and they wait until the off-season to see a doctor. By that time they might be very sick,” said Valladolid.

She added that the other health issue is opioid addiction, which “doesn’t discriminate based on age, class or education.” Getting off opiates can be difficult. Suboxone, a new drug for treatment of opioid dependence, isn’t widely available or often covered by insurance. When I asked what Congress, and by extension, her representative, could do to alleviate some of the health-care woes in the district, she demurred.

“We can’t just look to the federal government to fix problems. I want to see our representatives working together with health providers like us and with faith groups. It takes a whole village, not just government money.”

But she said that the expansion of Medicaid through Obamacare was helping many in the district and suggested that the very least government could do is no harm; that is, don’t take it away. “Patients have had a lot of fear about the possibility of the ACA going away," Valladolid said. "It would affect a lot of people who need constant coverage.”

Erin Gama, a paralegal who lives in Patterson, said, “I earn too much to get state assistance but not enough to pay for insurance without the ACA. It’s not a perfect law, but we can’t go back to the way the insurance market was.”

Pablo Paredes, who considers himself a progressive, said he has noticed more people talking about Denham’s vote for the ACHA. “Friends have become more politically active in the past several months, and they all attribute that to Denham’s vote on [Obamacare] repeal.” He wouldn’t speculate on whether that vote would be pivotal in November, but he said he was encouraged to see an increasing number of millennials and members of the younger “i-gen” cohort getting involved in politics.

Living The Dream

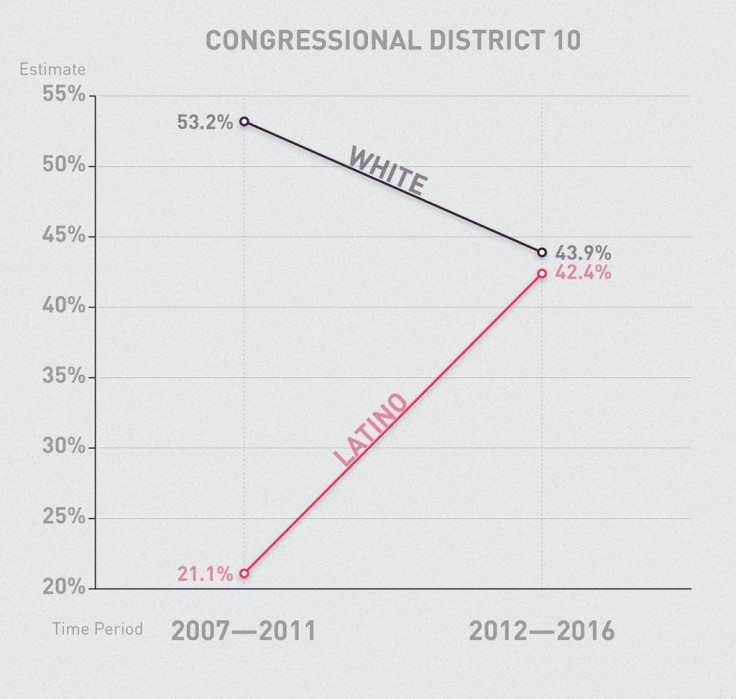

CA-10 has a Latino plurality of 43 percent. They are some of the least engaged voters in the district, said Melissa Santos, Stanislaus regional coordinator for Mi Familia Vota. “Latinos here typically have a low participation rate, about half of the actual capacity.” But Santos added that, even more than the Trump's administration rescinding of the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, Republicans’ vigorous campaign to repeal the Affordable Care Act has made many Latino voters in the district start to become politically active.

Denham has long touted his support for Dreamers, the young immigrants who were brought here by their parents. He has said more than 10,000 Dreamers, who “contribute more than $11.3 billion a year to the state’s annual GDP,” live in his district, and it’s one policy area where Denham has signaled a break with the conservative direction of Donald Trump. After Trump's administration ended DACA in September, Denham was one of 10 House Republicans who wrote a letter to Speaker Paul Ryan urging Congress to protect Dreamers. In January, Denham co-sponsored the Uniting and Securing America (USA) Act, a bipartisan bill to protect DACA recipients -- but while adding new border security measures.

Denham’s support for Dreamers has not always translated into a broader embrace of immigrant rights. In June, he voted for a bill supported by Trump that penalized states and localities that adopt sanctuary laws. In September he voted in favor of legislation that gives the government increased authority to deport or deny admission to immigrants suspected of being in gangs.

At the women’s march I met Levi Tull, 19, whose bright pink bow tie, worn “in solidarity,” made him stand out. He told me he wanted to see comprehensive immigration legislation and a “clean” Dream Act from Congress, and less incendiary rhetoric about immigrants from the White House.

Denham’s vocal support for Dreamers and insistence on a reasonable compromise on immigration has given him a sympathetic, pro-immigrant reputation that Tull says is unearned.

“That statement he signed with House members? That’s just words, and actions speak louder than words," Tull said. Tull was able to meet face-to-face with Denham once. “I noticed across the street an almond processing plant -- that wouldn’t even be possible without cheap, immigrant labor.

“My classmates, my coworkers, my friends, my family, they’re not criminals," Tull continued. "They pay their taxes. They are American in every way except on paper. It’s time for Congress to make that final step. They keep on being marginalized.”

A few days later, I talked again with Tull, when he was between classes at Modesto Junior College, where he studies political science. Tull, who was born in Modesto, told me several of his friends are Dreamers, including “one who is very scared right now and doesn’t want to talk about it.”

William Broderick-Villa, an attorney and lifelong resident of Waterford in the rural eastern part of the district, said many in CA-10 understand the importance and contribution of undocumented workers, which can lead to “inconsistent” opinions. “Some people will say the undocumented should be deported, but if you mention, ‘Well, your friend and neighbor is undocumented,' they will say, ‘Of course don’t deport him.’”

Pablo Paredes, a professor, organizational development consultant and member of the Modesto and Tracy Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, told me that he has seen more examples of nativist sentiment, mostly on social media, in the past year. “I marched for the Dreamers and I did encounter jeers from the side of the road, people telling us, 'Go home.' Okay, well I’m from Florida.” Paredes, who moved to Modesto from the Miami area three years ago, said he’s glad that nativism, while more pronounced than in south Florida, hasn’t made its way into the business community. Nor has political animus been an issue.

“The local business community is very respectful of political candidates of both parties at events and [there's] no outward hostility to differing political views. I find that refreshing,” Paredes said.

Copyright Capital & Main

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.