Belching Supermassive Black Hole Seen Giving Life To New Stars In Galaxy 26 Million Light-Years From Earth

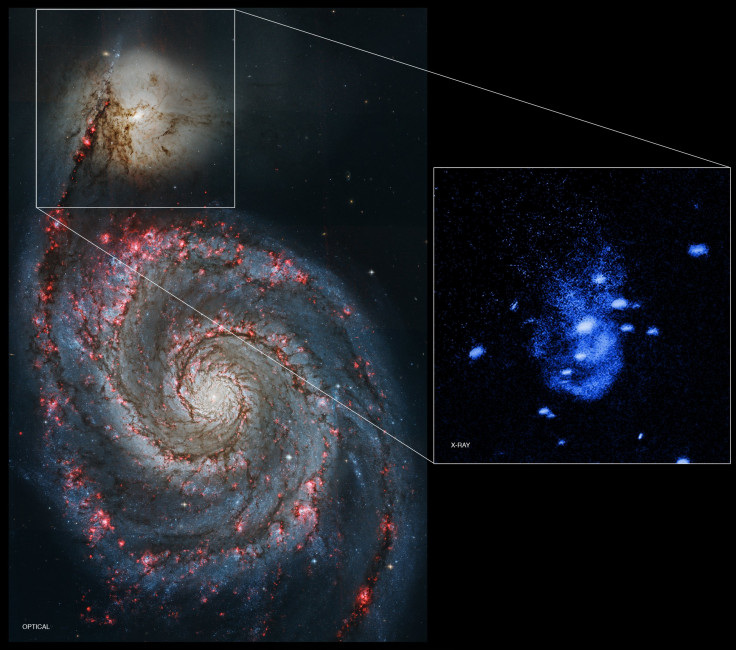

Astronomers using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory have detected a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy "burping," the space agency announced Tuesday. X-ray emissions were observed from the black hole at the center of the galaxy NGC 5195 -- located 25 million light-years from Earth. This act of galactic indigestion may have triggered the formation of new stars within the galaxy.

Supermassive black holes are usually caught snacking away on gas, dust or stars that have traveled too close to the center of the galaxy. After meals, black holes can eject some of the gas outward. "We think these arcs represent fossils from two enormous blasts when the black hole expelled material outward into the galaxy. This activity is likely to have had a big effect on the galactic landscape," co-author Christine Jones, from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), said in a statement.

Black holes -- through their eating habits, tendency to destroy things, and gravitational pull -- can limit the size of a galaxy. The energy emitted by a black hole could heat -- or eject -- the cold gas necessary for star formation, according to previous research.

In the case of the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy NGC 5195, the gas emissions pushed cooler helium gas together. This plowing effect could lead to the formation of new stars. "This shows that black holes can create, not just destroy," co-author Marie Machacek, from CfA, said in a statement.

NGC 5195 is a small galaxy that is currently merging with the larger spiral galaxy NGC 5194 -- better known as "the Whirlpool." The interaction between the two galaxies could have fed NGC 5195's black hole, leading to emissions observed by Chandra. "Our observation is important because this behavior would likely happen very often in the early universe, altering the evolution of galaxies. It is common for big black holes to expel gas outward but rare to have such a close, resolved view of these events," lead author Eric Schlegel, from the University of Texas in San Antonio, said in a statement.

The research was presented at the 227th meeting of the American Astronomical Society meeting in Kissimmee, Florida.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.