El Niño 2017: What Is It, Will We Get One This Year?

Despite El Niño and La Niña, the two parts of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle influencing the weather much of the United States sees, many people don’t understand what that cycle is, when it happens or why. Some extreme weather events can be attributed to the cycle that is completely natural and has been traced back hundreds of years.

The two phases of the ENSO cycle originate in the Pacific Ocean near the Equator and their names refer to whether there are colder (leading to a La Niña) or warmer than average (leading to an El Niño) water temperatures in the area, which can then cause certain weather patterns over North America.

Read: Hurricane Season 2017: What Are The Chances?

The two can cause extreme events like heavy rains, flooding and drought, which can have negative impacts on the water and food supplies, NOAA says. “When the ocean temperatures become warmer or colder than average, they impact the patterns of tropical rainfall, and that change in the pattern of rainfall impacts heating into the atmosphere, which ends up impacting the jet stream across the Pacific Ocean,” Mike Halpert, deputy director of the Climate Prediction Center, told International Business Times. The reason this matters to those of us in the United States is that a lot of weather moves west to east, and when it does, it brings what’s going on in the Pacific with it.

The last El Niño cycle took place during the 2015-16 winter, and it was one of the strongest ever. That season brought record wind shear and rainfall across much of the country. There are certain conditions associated with El Niño and La Niña. “It depends on where you are, certainly,” Halpert said.

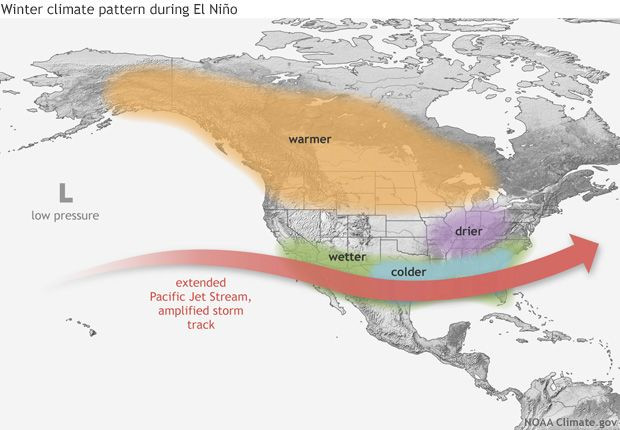

During an El Niño year, the northwestern part of the country is typically warmer while the southeastern part of the country, from Texas to Florida and even parts of California, see wetter conditions. On the other hand, La Niña can sometimes cause colder, more storm prone conditions in the north and the opposite in the south. Lighter wind shears also are associated with La Niña in the Atlantic, which doesn’t suppress storms and can create ideal conditions for hurricanes.

Read: California Has Been Getting Major Rainfall After Years Of Drought, But Why?

But while the oscillations make some weather events or patterns more likely, it’s no sure thing. “No two El Niños work out exactly the same, and El Niño is not the only thing that impacts seasonal variability, while it could play a large role these are certainly not guaranteed impacts,” Halpert said. The oscillations themselves are difficult to predict. Scientists really don’t know whether there is likely to be an ENSO event until a few months before it happens — even with the help of climate models.

The forecasts from the CPC are updated on the second Thursday every month. The conditions were “ENSO-neutral” Monday, meaning neither was particularly more likely to develop than the other through the fall in the Northern Hemisphere. “We’re able to generally forecast out maybe three to six months into the future with things like E l Niño,” Halpert said, “Further than that would just be a complete guess.” Computer models that predict what the atmosphere is doing and what the ocean is doing and how the two interact help provide forecasts for the cycles. Statistics also play a part, and computer models can look at current conditions and compare them to past conditions to see what followed those past conditions.

The general thought among climate scientists is an E l Niño event happens anywhere from every two to five years — it’s cyclical but fairly random. La Niña comes interspersed in that range. There have been stretches of time, six or seven years, without events, but on average, these events are more frequent than that, Halpert said.

But with the forecast looking like we might not get one this year, there’s no way of really knowing when the next ENSO event may happen. “If we don’t see El Niño this year, looking further out there’s no way of saying, ‘Well if we didn’t get it this year we’ll get it next year,’ all kinds of variability and things can happen,” Halpert said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.