Fear Of ISIS Attacks In Libya Shuts Down Major Oil Fields

BEIRUT — Mohammed Zeidani is out of a job — and the Islamic State group is to blame. The 26-year-old native of Benghazi, Libya, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, worked as a petroleum engineer with Schlumberger, the world’s leading oil and gas company, for four years before he became an independent contractor last year. But the Islamic State group, the terrorist group best known as ISIS, has ensured that Zeidani no longer has work in Libya’s eastern desert oil fields.

Five of the country’s functioning oil fields were shut down in the past few days and their employees were evacuated. The Zeltan oil field, owned by the state-run National Oil Corp. and the largest in the eastern Sidra Basin, was the last to be evacuated. After seeing two vehicles branded with the distinctive black and white ISIS flag in the vicinity of the facility, employees went on strike Tuesday.

The workers said they were “forming a crisis committee and stopping production activities” in Zeltan, according to a statement obtained by Middle East Eye.

In a country where unemployment is rampant, disbanding functioning oil fields may seem counterintuitive, but Libya’s oil workers know something worse than being out of work is headed their way:

Staff evacuated from oil fields in fear of IS#Fezzan #Libya https://t.co/booZMb2DVG pic.twitter.com/qnevwIS7Ly

— Fezzan Libya MG (@FezzanLibyaMG) April 12, 2016

“There have been attacks on oil fields. All attacks [were] by ISIS,” Amin Mneina, a regional engineer at an international development company who formerly worked at an oil field, told International Business Times. “The National Oil company has been warning fields [about] expected attacks and [advised] evacuating the fields that are thought to be in danger of an armed attack.”

In recent weeks, ISIS has increased the number of assaults in and around its northeastern Libyan stronghold of Sirte, leaving oil and gas employees in the area concerned that militants will try to seize their facilities — home to roughly 80 percent of Libya’s oil reserves.

Oil is Libya’s most treasured resource, but control and security of liquid gold has become as fractured as the country’s divided political system. The ensuing chaos has seen oil production in Libya plummet, and the recent ISIS threat to the essential commodity will likely see production fall even lower.

U.S. interests were also affected by the closures. Closed this week were the Waha and Samah oil fields, operated by the Waha Oil Co. (WOC), a subsidiary of the National Oil Corp. (NOC). Though WOC is the primary operator for both fields, the two are a joint venture between WOC and American oil companies ConocoPhillips, Marathon Oil and Hess Corp.

“The financial situation is dire no matter what the authorities say. There needs to be more [emphasis] on how to solve the problem. Part of that is boosting oil production,” Claudia Gazzini, a Tripoli-based senior analyst for Libya with the International Crisis Group, recently told IBT. “The more divided [the country is], the more the financial situation goes down the drain — rival banks and oil companies.”

Hundreds of Libyan oil and gas workers have lost their jobs since mid-2014, when a rival government seized the country’s capital, throwing the oil-rich country into economic free fall. Before the fall of dictator Moammar Gadhafi in 2011, Libya was producing roughly 1.65 million barrels daily, more than three-quarters of which went to European countries. Today, amid a power vacuum that dozens of militias have tried to fill, production is down to some 400,000 barrels per day.

At the beginning of the civil war, major international oil and gas companies shut down their operations due to deteriorating security in the country and unemployment rose sharply. European companies, including Italy’s Eni and France’s Total, significantly scaled back operations. The situation deteriorated further this January when ISIS began its assault on Libya’s oil and gas resources: Militants attacked the Es-Sidra and Ras Lanuf oil export terminals in Sirte, home to roughly 80 percent of the North African country’s recoverable oil reserves, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“[The] bulk of oil is being pumped in the east ... of course there’s a lot of damage if ISIS gets hold of it,” a Libyan-American activist recently told IBT.

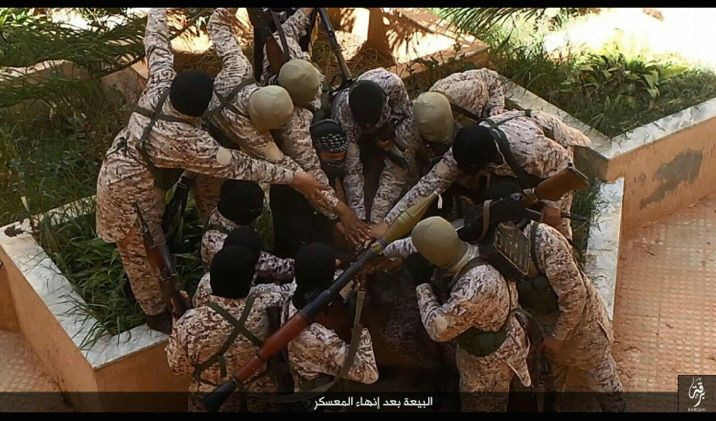

#Libya #ISIS is mobilizing fighters to capture the #Mabruk Oil Field in Southern #Libya.#Tripoli pic.twitter.com/L8ZWaKpHhw

— WorldOnAlert (@worldonalert) April 9, 2016

The political situation seemed to be improving last month, when the United Nations brokered a deal to form a unity government backed by the NOC, but, in the absence of support from the most powerful ruling militias on the ground, including those controlling Libya’s vast oil reserves, the toothless governing entity has yet to make its mark.

The exodus of foreign firms last year meant that much of Libya’s oil resources were turned over to the NOC and its subsidiaries, which have a monopoly on trading Libya’s oil resources and own four of the five facilities closed this week. Securing the oil fields is the responsibility of Libya’s Petroleum Facilities Guard, a militia of roughly 27,000 fighters that operates in the east and southeast to protect “the fields and evacuate workers in case of attacks,” said Ahmad, a Libyan activist from Tripoli. The group was originally aligned with the Libyan army but has since split along the lines of Libya’s complex civil war, leaving the fields vulnerable to attack from the Islamic State group.

With the ISIS threat in the east, Zeidani is heading west, to Bouri, an offshore oil field that’s part of a joint venture between Italy’s Eni and Libyan company Mellitah Oil & Gas B.V.

“Foreign companies don’t want to work in the desert, they are afraid of ISIS,” Zeidani told IBT. “Bouri is working normally, because there’s no ISIS in the sea!”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.