Greek Debt Crisis: What Will A Third Eurozone Bailout And More Austerity Do To The Greek Economy?

Facing a paralyzing banking crisis and the looming specter of an exit from the eurozone, Greece has until midnight Thursday to cobble together a proposal that would satisfy its creditors.

At the center of the tensions is the issue that propelled Syriza, Greece’s upstart radical-left government, to power last January: austerity.

After major economic reforms in 2010 and 2012, popular anger spilled onto the streets as Greeks endured steep tax hikes, public-sector layoffs, pension reductions and sweeping cuts in welfare and public services -- all in response to lenders’ demands that Athens shrink spending to pay back its debts.

Many Greeks now view those policies as deep and lingering wounds. As Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras declared in a speech before the European Parliament Wednesday, “The mistakes of the past condemned the Greek economy to a period of never-ending impasse.”

Many liberal economists in the U.S. -- chief among them Paul Krugman -- share that basic view. “The medicine prescribed by the German Finance Ministry and Brussels has bled the patient, not cured the disease,” the world-renowned inequality theorist Thomas Piketty and four other economists wrote in an open letter to German Chancellor Angela Merkel this week.

But that sentiment has also been aired by a key member of Greece’s lending bloc, called the troika and composed of the European Commission, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund. In 2013, the IMF admitted it had miscalculated the damage austerity would do to Greece’s economy -- and thus its ability to raise revenue and pay back its debts.

Still, finance ministers in Germany and other eurozone nations maintain that austerity must continue, pointing to enduring inefficiencies in Greek government spending and taxation. The troika’s proposals involve scraping together greater government surpluses, raising taxes and deepening pension cuts.

But given the economic ruin of the past five years, is the medicine the troika hopes to apply the wrong prescription?

History Repeating

If the third bailout ends up being anything like the first two, Greeks might have reason to worry. In 2010 and 2012, Athens assented to unusually deep austerity measures. Greek spending on public-sector employment, which was considered exorbitant before the global financial crisis, dropped by one-third over five years. Tens of thousands of government employees got the boot.

To meet ambitious spending goals, the government also slashed social services and welfare programs. By 2015, at least 800,000 Greeks lacked access to medical care, with hospital budgets cut by one-quarter and pharmaceutical spending halved. Childhood poverty now stands at 40 percent.

The broader economic effects were similarly hard to miss. Unemployment surged above 27 percent, as Greek economic output sunk by one-quarter between 2010 and 2015. More than 200,000 Greeks left the country’s Mediterranean shores for a brighter future.

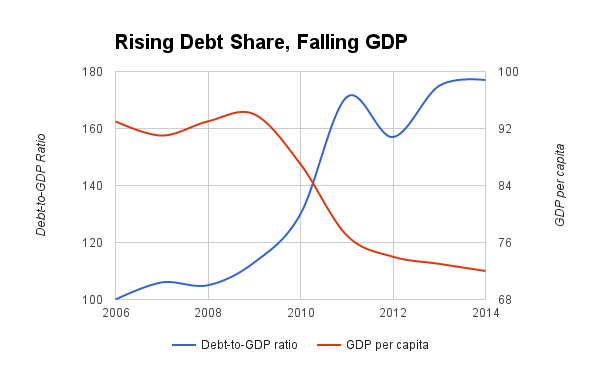

And yet the metrics debt hawks were scrutinizing actually moved in the wrong direction. The ratio of Greek debt to gross domestic product rose, largely because economic activity had bottomed out.

Meanwhile, even as deep pension cuts left Greek retirees earning at least 27 percent less than they had previously, the share of pension-benefit spending in the economy rose to 17.5 percent, the highest in Europe. Although the trend was partly fueled by a surge of early retirements spurred by layoff fears, the number chiefly reflects GDP contraction.

Other economic benefits failed to materialize. With wages sinking, the Greek economy was expected to become more competitive. But exports barely budged after the bailouts, as entrenched structural barriers and soaring energy costs kept domestic industrial activity in check.

As University of California-Irvine economics professor Stergios Skaperdas explained, austerity measures created an economic ripple effect. The deep government spending cuts and wage freezes left less money in ordinary Greeks’ pockets. That means less spending and less demand, further undercutting an already shaky economy.

“It is like having a debt slave who is worked gradually to death,” Skaperdas said. The more bread one demands from the debtor, the harder it is for him to labor and make ends meet.

The Latest Plan

Still, many economists see structural reforms a necessity for Greece. Skaperdas, a critic of austerity, makes some concessions, namely, closing tax loopholes and instituting pension reform. “Improving the functioning of the Greek state would be nice,” he said.

And to many, even painful measures may be worth it if it means staying in the eurozone and avoiding a potentially disastrous split from it.

Before a July 5 national referendum called by the Greek government to muster support for its bargaining position, a coalition of 246 Greek economists signed a letter repudiating the government’s position. They expressed fear that rejecting the troika’s terms would lead to an exit from the eurozone and certain calamity.

At the same time, however, they wrote that the bailout agreement “should be characterized by the lowest possible recessionary consequences and the highest possible level of social protection.”

And despite the combative stance of Greek negotiators, the dueling proposals from the troika and Greek finance team differ on just a few key points.

In the broadest economic measure, European governments holding the lion’s share of Greece’s debt demand primary surpluses of 1 percent in 2015, increasing to 3.5 percent by 2018. In essence, that means Greece must increase the share of tax revenue it takes in while cutting its spending. Greek negotiators have previously approved these targets.

Taxes present a stickier issue. Like most of Europe, the Greek tax system uses the so-called value-added tax, which adds a surcharge at each stage of the production process rather than only at the cash register. The troika would have Greece simplify its tax rates, which vary by industry and region, and broadly raise rates. But differences remain, particularly around Greece’s lower taxes for remote islands (which happen to benefit a political party central to Syriza’s ruling coalition).

Finally, there’s pensions, the thorniest issue in the talks. Greek leaders have emphasized that with a hobbled welfare state, pensions are all that separate many families from destitution. One-half of Greek households rely on retirement spending to get by, even as 45 percent of pensioners live at or below the poverty line, according to the Greek government.

Creditors would like the retirement age to be raised to 67 by 2022, sooner than Athens would like. But more contentiously, the troika wants to shear away so-called top-up benefits added to base pension payments. European lenders would like to see those top-ups eliminated by 2017 -- again, far earlier than Syriza can stomach.

Overall, Skaperdas worries the spending cuts and tax hikes could amount to another chapter in the continuing saga of Greek bailouts and austerity. “The proposals that Greece might have to agree to by Sunday might imply even more cuts,” he said.

And compared with 2010 and 2012, Skaperdas said, “It could be much worse.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.