In Myanmar, Garment Factories That Source Popular Brand-Name Clothing Retailers Aim To Defeat A 40-Cent Hourly Minimum Wage

Factories in Myanmar that supply major Western clothing companies are fighting a government proposal to set the country’s first-ever minimum wage at roughly $3.25 a day. At the same time, the brands themselves -- Gap Inc. and H&M Hennes & Mauritz AB among others -- have declined to say where they stand on the proposed rate, which amounts to 40 cents an hour.

The ongoing debate, pitting the government against a burgeoning export-driven garment-manufacturing sector, sheds light on the spectacular competitive pressures that define the global apparel industry. It also exposes a clear divide between the views of on-the-ground suppliers and the public assurances of brands they serve.

In the last few years, top Western clothing retailers such as Gap, H&M, Marks and Spencer Group PLC and Primark Stores Ltd. have signed contracts with more than a dozen garment factories in Myanmar, the former British colony also known as Burma. The country emerged from decades of military dictatorship in 2011 and major U.S. and European sanctions shortly thereafter. It now offers some of the cheapest labor costs on the planet combined with easy access to Asian markets -- both attractive features for corporations looking to source low-cost, ready-made garments for export.

Last summer, Gap raised eyebrows when it became the first American apparel company to publicly sign a contract in Myanmar since President Barack Obama eased sanctions. At the time, Gap said, “The apparel industry will play a key role in helping to fuel the economic prosperity of the country.”

But if garment-factory bosses get their way, comparatively little of that newfound wealth will flow to workers.

The Myanmar Garment Manufacturers Association, representing about 350 factories, says the government’s proposed wage is too high and will force employers out of business. It wants its own industry-specific rate of about $2 a day instead. Starting pay in factories currently hovers around $1 a day.

An association official recalled a meeting two weeks ago that brought together representatives of about 160 factories, including the owners of plants that supply Gap and H&M, to discuss the government’s wage proposal. “At one point, we did a roll call vote to see a show of hands, who would say basically they couldn’t afford to pay it, and every hand went up,” says the group’s project manager Jacob Clere, reached on the phone in Yangon, the nation’s largest city and garment-manufacturing hub. “In terms of the membership, they’re all saying they can’t afford to pay it.”

That sentiment contrasts sharply with the repeated public assurances of brands that say they are committed to improving labor standards in Myanmar.

The newly arrived Western companies, especially Gap and H&M, have trumpeted their support for improved working conditions, voicing concerns over issues such as forced labor, unfair overtime demands and unpermitted subcontracting, while backing the idea of a national minimum wage. In 2013, Burmese officials first announced plans to set a minimum wage, organizing a tripartite commission with representatives of employers, trade unions and the government to come up with a figure. Now that those talks have finally produced a number, Western brands are keeping quiet.

When asked by International Business Times for their views on the proposed rate and the opposition from subcontractors, both Gap and H&M distanced themselves from factory-owner demands to create a two-tier pay system, but declined to endorse the $3.25 rate that’s on the table.

Jeffrey Vogt says all foreign retailers should endorse at least the proposed wage, if not a higher rate backed by trade unions. “They definitely have a responsibility to speak out for a higher wage, a livable wage for workers,” says Vogt, director of the legal unit at the Brussels-based International Trade Union Confederation, the world’s largest labor confederation. Right now, most garment factories in Myanmar resemble classic sweatshops, he says. “You have all the typical issues, health and safety issues, long hours, low wages, unpaid wages, lack of overtime [pay] and discrimination against unions.”

Irene Pietropaoli, a researcher with the Business and Human Rights Resource Center headquartered in London, says there’s no question Gap and H&M could influence the wage debate if they felt so inclined. Since Burmese authorities are so committed to attracting foreign investment, they tend to listen closely when high-profile companies sound off on the business environment. At the very least, she says, Western brands could encourage factories they source from not to fight the government proposal. “They really have a strong influence,” she says.

Companies have few, if any, legally binding obligations to improve labor conditions. Nevertheless, Vogt points to guidelines from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The group of economic powerhouses calls on multinationals operating in developing countries to offer pay and working conditions that meet “the basic needs of the workers and their families.”

In the garment industry, that’s not always the case, he says.

A 2013 report by labor-rights advocates shed light on working conditions in the industrial zones outside Yangon, where garment production has soared. Workers complained of low pay, forced overtime, late-night work, wage deductions and few days off.

The Race To The Bottom

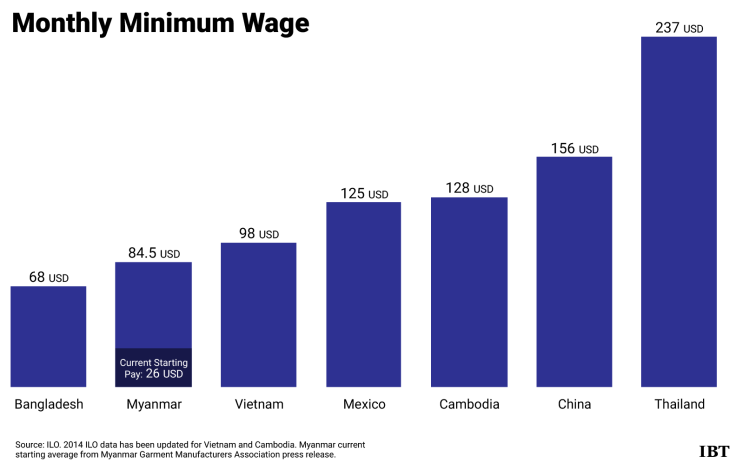

Myanmar attracts foreign apparel companies -- many of them from China and South Korea, but increasingly from the U.S. and Europe -- for one main reason, Vogt says. It’s very cheap. “When you look at labor costs in Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh, they’re all extremely low, but much higher relatively,” he says. “They’re going for the low wages and least difficult regulatory environment.”

During the past couple of decades, the hunt for low-cost labor has driven global clothing brands from factories in the U.S. and Europe toward Mexico, Central America, China and, most recently, Southeast Asia. The April 2013 collapse of the Rana Plaza complex, a disaster that killed more than 1,000 garment workers, brought attention to the industry’s recent pivot toward Bangladesh. Dozens of American clothing retailers, including Target Corp. and Wal-Mart Stores Inc., have signed contracts with factories there, where the monthly minimum wage stands at a paltry $70. Still, that’s steep compared with Myanmar, which has no private-sector wage floor.

This year, the U.K.-based risk-analytics firm Verisk Maplecroft found Myanmar had the second-lowest labor costs in the world, barely beating out its regional neighbors, Vietnam and Cambodia. Out of 172 countries, only Djibouti had lower costs than Burma, researchers concluded.

Factory owners view this as an asset. Ahead of the manufacturing lobby’s 2014 convention, the group’s website noted: “Outsourcing labor to Myanmar offers significant cost savings to Western manufacturers, as Burmese workers are among the lowest paid in Asia, earning an average $2 per day versus $20 per day in neighboring Thailand.”

Wages, of course, aren’t the only costs of doing business.

Other regulatory expenses add up -- things like supplying the proper protective equipment, installing the correct ventilation systems and following fire codes. In Myanmar, these costs are minimal, as factory owners follow bare-bones safety and health regulations last updated in 1951. While critics have slammed Bangladeshi authorities for failing to properly enforce building regulations in the run-up to the Rana Plaza disaster, Myanmar has no national building code to begin with. As is the case with the minimum wage, the government is still in the process of rolling it out.

Gap has acknowledged the dangers of doing business in such an environment. In a voluntary submission to the U.S. State Department last year, the company noted Myanmar’s “limited rule of law and underdeveloped regulatory regime” create “potential human-rights and business risks.”

Against this backdrop, the trade-union confederation’s Vogt says a modest minimum wage is a reasonable step toward improved standards. There’s “no question Myanmar’s going to be competitive,” he says of the proposed figure. “I think a lot of it is posturing. They’re trying to scare the government into re-adjusting the wage rate.”

Not so, says the factory association’s Clere. He says the threat of losing business is real, and the wage debate is already having an impact on investors from China, Thailand, South Korea and Japan. Since the government has unveiled its proposed rate, dozens of factory owners have already threatened to leave.

“We’ve seen a lot of investors going into a kind of holding status, where they’re not investing in new factories as much,” Clere says. “I do think it’s a sensitive situation. It’s a very globally competitive industry and a very regionally competitive industry.”

Under the new rate, Myanmar would still have a lower wage than its competitors. But the country has more expensive overtime pay obligations -- about twice the hourly rate when employees work more than 44 hours per week -- than its neighbors. If the government’s proposed rate takes effect, Clere says, the country will end up being “barely competitive with Vietnam and Cambodia.”

Clere says: “Myanmar arguably can’t afford to be barely competitive with these countries right now. They have to have some attractive feature. And one of the attractive features for the industry is cost-competitive labor.”

Correction: The chart has been updated to reflect new minimum wages in Vietnam and Cambodia. It also converts Myanmar's proposed daily minimum into a monthly minimum on the basis of a six-day work week -- a metric used by the International Labor Organization when comparing wages between countries. An earlier version of the chart relied on a five-day work week and therefore underestimated the rate of monthly compensation under the current proposal.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.