NASA’s Hubble Spots New Stars In Distant Galaxy, Seeing Them As They Appeared 11 Billion Years Ago

Among the farthest-discovered, newly formed stars are a whole clump of young, blue stars in a galaxy so far away that we see it only as it existed 11 billion years ago. Given the distance, despite its impressive powers of observation, even NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope needed help in seeing these stars, and this help came from both natural gravitational lensing and human-made computer code.

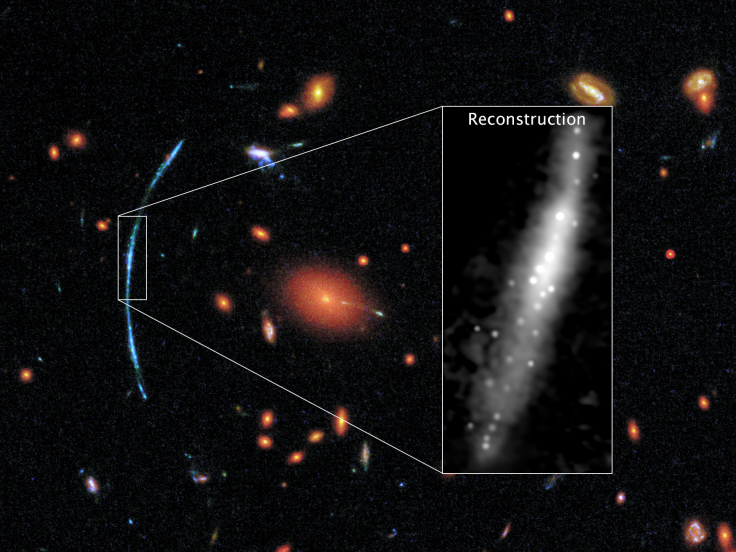

The galaxy in question, SGAS J111020.0+645950.8, is a disk galaxy and is one among the over 70 Hubble study targets identified by the Sloan Giant Arcs Survey. It appears as a large spotty blue arc in a Hubble photo, having been gravitationally lensed by the galaxy cluster SDSS J1110+6459, which was imaged as part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

Read: Gravitational Lensing Allows Hubble To Spot Universe’s Brightest Galaxies

Gravitational lensing is a phenomenon wherein a foreground object with very strong gravity — in this case, a galaxy cluster — bends and magnifies the light of objects behind it, allowing us to not just see the background object — in this case, the star-forming disk galaxy — but also magnified. The disk galaxy in the image above is magnified about 30 times due to this effect. The red galaxies that appear in the image are older, and therefore more redshifted.

However, the magnification also causes distortion in the image, and to resolve that to make the galaxy look as it would appear normally, a computer code was created and applied. It shows about two dozen clumps of newly formed stars, each clump about 200-300 light-years in size.

“When we saw the reconstructed image we said, ‘Wow, it looks like fireworks are going off everywhere’,” astronomer Jane Rigby of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a statement Thursday. Rigby was also one of the co-authors of a paper on the subject that appeared online Thursday in the Astrophysical Journal.

Considering this galaxy appears to us as it was only 2.7 billion years after the Big Bang, its observation is in direct contradiction of present-day theories that speculate star-forming regions in the early universe to have been much larger at over 3,000 light-years across.

Read: Hubble Finds Massive Galaxies Aligned With Their Surroundings 10 Billion Years Ago

“There are star-forming knots as far down in size as we can see,” Traci Johnson, a doctoral student at the University of Michigan and lead author of the paper — titled “Star Formation at z = 2.481 in the Lensed Galaxy SDSS J1110 = 6459. I. Lens Modeling and Source Reconstruction” — said in the statement, and added that the galaxy would have seemed perfectly ordinary to Hubble were it not magnified by gravitational lensing.

When NASA launches Hubble’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, in October 2018, the more powerful device “will uncover older, redder stars that formed even earlier in the galaxy's history. It will also peer through any obscuring dust within the galaxy,” the statement said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.