NASA’s InSight Mars Lander Passes Solar Panel Array Unfurling Test

The next spacecraft NASA is sending to Mars is not a rover or an orbiter, but rather a lander. Rovers move about on the surface while orbiters stay in orbit around the planet, but landers remain stationery in one place and go about their business.

Called InSight (short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport), the lander is currently scheduled to take off sometime in May 2018, and once it reaches Mars (in November, if there are no delays in the launch), it will study the interior of the red planet. Like its name suggests, InSight will study seismic activity, subsurface heat and the general interior structure of Mars.

"Think of InSight as Mars’ first health checkup in more than 4.5 billion years. We’ll study its pulse by 'listening' for marsquakes with a seismometer. We’ll take its temperature with a heat probe. And we’ll check its reflexes with a radio experiment," Bruce Banerdt of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the mission’s principal investigator, said in a statement Wednesday.

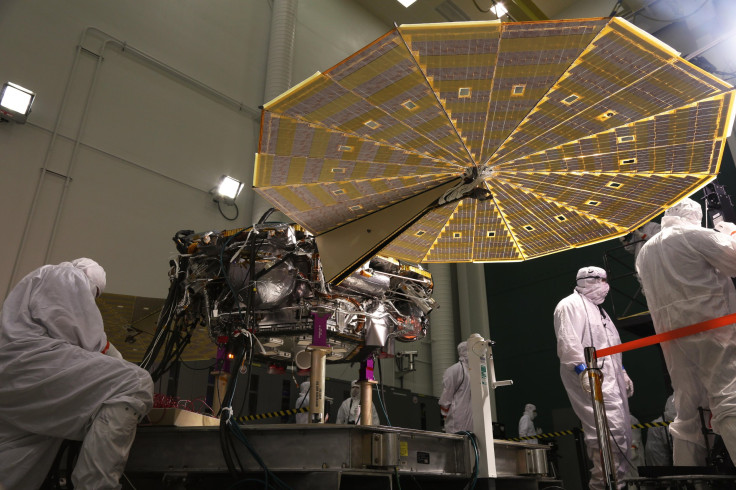

To do all this, the spacecraft is fitted with different instruments, which are powered by two arrays of solar panels. These panels are designed like fans, especially configured like that to maximize the energy output from the weak sunlight on Mars, given the planet’s distance from the sun and its thin, dusty atmosphere.

On Tuesday, the panels successfully passed a test in which the solar arrays extended to their full length. Engineers and technicians verified that the solar arrays fully deployed, and also conducted an illumination test to confirm that the solar cells were collecting power.

"This is the last time we will see the spacecraft in landed configuration before it arrives at the Red Planet. There are still many steps we have to take before launch, but this is a critical milestone before shipping to Vandenberg Air Force Base in California," Scott Daniels, manager of the InSight Assembly, Test and Launch Operations at Lockheed Martin, said in the statement.

InSight was built at a Lockheed Martin Space facility outside Denver, which is also where the Tuesday test took place. Along with the test, engineers also attached a microchip to the spacecraft which has 1.6 million names inscribed on it. The names, submitted by the public, are in addition to the over 800,000 names that were on another chip attached to InSight in 2015.

"It’s a fun way for the public to feel personally invested in the mission. We’re happy to have them along for the ride," Banerdt said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.