North Dakota Police Use Drone To Arrest Fleeing Drunk Driving Suspects [VIDEO]

Four North Dakotans have earned the dubious distinction of being the first Americans to be arrested with the help of a local police drone.

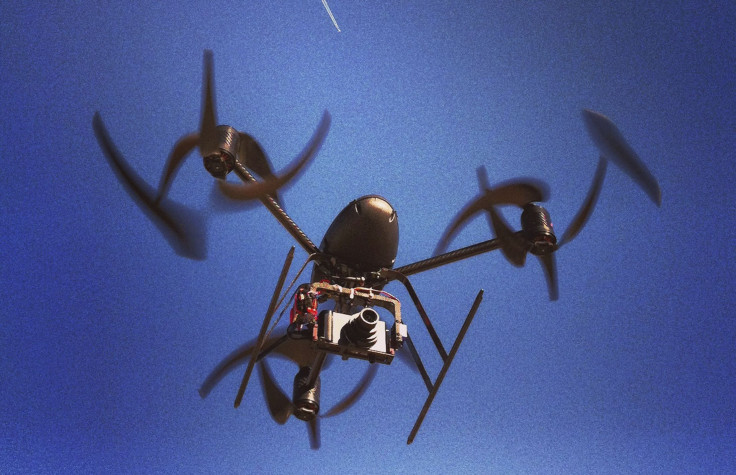

The four men were pulled over around 2:15 a.m. on Sept. 28 by a Grand Forks County sheriff’s deputy. When the sirens came on, though, they dashed from the car in separate directions. Rather than give chase, the police tracked the suspects with Qube, an aerial drone with four rotor blades, much like those widely used by hobbyists.

A favorite of drone-equipped police agencies throughout the U.S., Qube drones are three feet long and weigh about 5.5 pounds each.

Last year North Dakota police arrested a man with a Predator drone on loan from the Department of Homeland Security, in what was the first drone-aided arrest in the country. Last week’s arrest marks the first time police have used a UAV owned by a municipal department at night to take suspects into custody, the sheriff’s office told Fargo’s Valley News Live.

“One of them was walking through a cornfield. It took about three minutes to find him,” Alan Frazier, the deputy in charge of Grand Forks’ unmanned aerial vehicle system unit, told Vice News. “The other was found on a second flight, after maybe 25 minutes.”

The others were arrested not long after. The cornstalks measured 7 to 10 feet high, an obstacle that could have taken a group of officers hours to overcome. The Qube drone, though, was equipped with thermal-imaging technology capable of scanning for a suspect’s body heat, freeing up officers to search elsewhere.

Grand Forks’ UAV team has flown practice missions at night in the past, but this is the first time the department was allowed to launch an operational mission in the dark after receiving permission from the Federal Aviation Administration in March 2014. Rodney Brossart was arrested near his Lakota, N.D., farm in 2012 after a dispute with a neighbor over roaming cattle ended with a Predator drone showing police where Brossart was hiding.

While privacy advocates have stressed using caution in the future, nine out of 10 North Dakotans polled by a state committee said they have little quarrel with the idea of UAVs buzzing overhead as long as they’re used to resolve hostage standoffs, search for missing persons or respond to disasters. Traffic enforcement and the detection of illegal fishing or hunting found less support, according to the Guardian.

Grand Forks police told Vice the department has flown the Qube drone on 11 occasions and only once before, unsuccessfully, in a search for a fugitive. Frazier, the Grand Forks deputy, said the department should “absolutely not” have to obtain a warrant before flying a drone, and that drone warfare in the Middle East combined with dramatic media reports have turned “drone” into a bad word.

“There’s a misnomer that there are covert spy tools,” Frazier told journalist Jason Koebler. “We utilize them for events that are already occurring. We look for felony suspects, we do further analysis, we use them for totally overt missions. There’s no plans to use them overtly.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.