Obama Climate Change Plan To Cut Methane Emissions From Oil And Gas Industry Lacks Regulatory Muscle, Enviros Say

The Obama administration’s plan to cut methane pollution from U.S. oil and gas operations doesn’t have enough regulatory muscle to beat back the dangerous greenhouse gas, environmental experts say. The White House announcement Wednesday drew tepid praise from green groups, while some scientists criticized officials for downplaying the scope of the methane threat.

The proposals would work to reduce methane leaks at oil and gas sites and along pipeline networks. Faulty equipment and leaky systems cause more than 8 million metric tons of unburned methane to seep into the atmosphere each year -- the climate equivalent of running 180 coal-fired power plants. Federal regulators say they will set new standards to minimize leaks in new and modified oil and gas systems, while officials and companies will work together to craft voluntary guidelines for existing facilities.

The White House aims to cut oil-and-gas methane emissions to 45 percent below 2012 levels within 10 years -- the first goal of its kind in the nation.

But environmental experts say it will be extremely difficult to achieve that goal without adding more teeth to the president’s plan. Existing oil and gas systems, for instance, will remain virtually off the hook in terms of federal regulations, even though these systems make up 90 percent of the industry’s methane emissions. “The plan is only addressing part of the problem. They’re not tackling the lion’s share of current emissions,” Jeffrey Deyette, a senior energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a science advocacy group in Massachusetts, says.

Even so, Deyette praises the White House for making its largest move yet against methane emissions. “This is one of the areas that the administration hasn’t addressed significantly yet, so this is a real positive step,” he says.

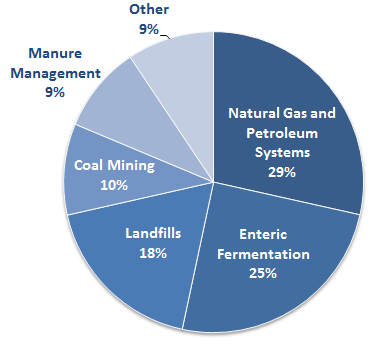

Until now, most U.S. efforts to tackle climate change have focused on carbon dioxide emissions, which are produced by burning oil, coal and natural gas and account for most of the country’s greenhouse gas pollution. (In June, the Obama administration proposed landmark regulations to cut carbon from existing power plants, which could be finalized this year.) Methane is emitted primarily from leaky oil and gas wells, though some of it comes from industrial landfills and mountains of manure in large agricultural operations. While methane is less abundant than carbon, it's dozens of times more potent, meaning that relatively small amounts of methane can have an immediate and powerful impact on global warming.

Regulators and climate scientists have grown more concerned about methane in recent years as America’s shale oil and gas boom explodes. In most cases, drilling in shale formations requires hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, a process that leads to methane leaks if production equipment isn’t properly sealed and monitored. Shale gas now accounts for 40 percent of total U.S. natural gas production, up from around 5 percent in 2007, according to federal energy data. Shale crude oil production has more than doubled since 2010, rising to more than 3.2 million barrels per day in the fourth quarter of 2013.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that methane accounts for nearly 10 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. But Deyette and environmental scientists argue that figure is too low because it is based on outdated information. They say methane likely makes up one-third or more of total U.S. emissions.

“They’re underestimating the importance of methane” and therefore downplaying the need to curb methane leaks, Robert Howarth, a Cornell University professor who studies methane emissions from natural gas drilling, says. “If you totally underestimate the extent of the problem, then your solution is going to be inadequate as well.”

Global climate experts initially thought that methane was 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide as a heat-trapping gas over a span of 100 years. This is the figure the EPA still cites. But an updated report by the United Nations-led Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated that methane is 34 times more potent over the span of a century. Most notably, it found that methane is even more dangerous in the short term, with 86 times the global warming potential of carbon over a 20-year time frame, and 100 times the potency over the course of a decade, according to the 2013 report.

This means that short-term bursts of methane can speed up the rate at which the planet warms. The world is on track to rise by 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) over pre-industrial levels in the next two decades, and it will likely reach 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) by mid-century unless countries dramatically reduce the amount of methane, carbon and other gases they pump into the atmosphere. As a result, sea levels will rise, weather patterns will change and extreme storm events will become more frequent and intense all across the planet, climate scientists say.

“If we cut global methane emissions, we buy ourselves a considerable amount of time and we considerably slow the rate of global warming,” Howarth says. “I think we [the U.S.] need to move much more quickly on that.”

White House and EPA officials insist their newly unveiled methane measures can help the U.S. meet the 45 percent reduction target. “We’re not going to get there overnight … [but] we’re confident the steps we’re outlining today will put us on a trajectory toward that goal,” Dan Utech, Obama’s special assistant for energy and climate change, said on a press call.

Janet McCabe, the acting assistant administrator for the EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation, says that the steps “will protect the public health and environment of this country, ensure safe and responsible oil and gas operations and allow the energy sector to continue to grow.”

She says the EPA will formally propose its rules for new and modified oil and gas systems by the middle of this year and will finalize regulations sometime in 2016. For existing facilities, the EPA will work closely with shale-rich states, including Colorado and Texas, as well as oil and gas companies to set voluntary standards for minimizing methane leaks. “This recognizes the extensive work companies are already doing to cut pollution,” McCabe said on the press call.

According to the EPA, methane emissions from the oil and gas industry have actually dropped 16 percent since 1990, though they are projected to rise by 25 percent in the next decade if steps aren’t taken to reduce additional emissions.

Oil and gas industry groups say the fact that companies are tackling methane on their own renders the Obama administration’s initiative unnecessary and burdensome. Jack Gerard, president and chief executive of the American Petroleum Institute, the industry’s main lobby group, says the methane initiative is “based on politics.” “As oil and natural gas production has risen dramatically, methane emissions have fallen thanks to industry leadership and investment in new technologies,” he said in a statement. “And even with that knowledge, the White House has singled out oil and natural gas for regulation.”

Mark Brownstein of the Environmental Defense Council’s U.S. climate and energy program rejects the notion that companies could sufficiently regulate themselves or that the EPA’s voluntary guidelines could have a meaningful impact on methane pollution.

“The pattern more often than not is for the vast majority of companies to hang back and wait to be essentially forced to come up to speed,” he told reporters on a separate call. “The only way that we can be sure that the entire industry is adhering to best practices is by setting a regulatory framework that really sets a floor for what is appropriate operating and technical practice.”

One bright spot for both industry and regulators is that fixing methane leaks is relatively easy to do, if the political will and corporative initiative is there. A study commissioned by the Environmental Defense Fund found that the oil and gas industry could cut methane emissions by 40 percent or more using existing devices and monitoring technologies. The upgrades would cost just one penny per thousand cubic feet of natural gas produced, according to ICF International, the report’s author.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.