Supreme Court Liberals Raise Civil Rights Concerns Over Arizona Immigration Law

Racial profiling challenges were off limits at Wednesday's U.S. Supreme Court arguments on Arizona's strict immigration enforcement law. Yet civil rights concerns were on the liberal justices' minds as they asked how the law will actually work on the ground.

At the outset of testimony from U.S. Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, Chief Justice John Roberts bluntly asked the president's main Supreme Court lawyer to affirm that racial and ethnic profiling were not part of the suit. Verrilli agreed, as the government's main challenge to the law is that federal immigration statutes override key provisions of Arizona's enforcement scheme, which has been blocked by lower court judges.

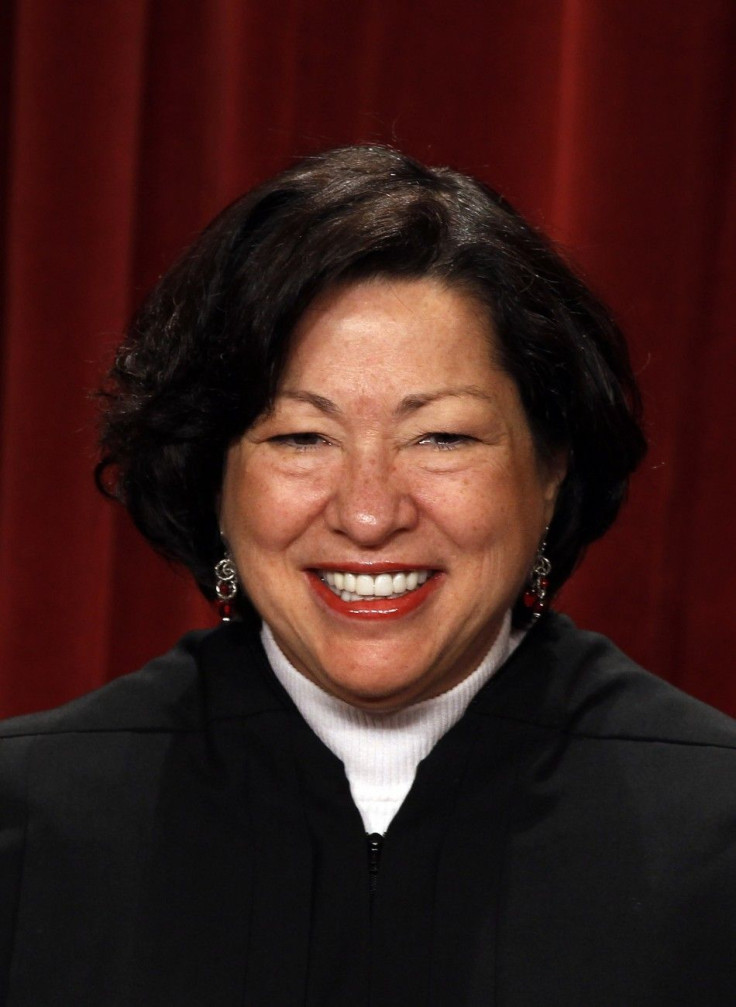

Still, the liberal justices -- minus Justice Elena Kagan, who recused herself as a recent solicitor general -- raised concerns that the law could lead to extended detentions for immigrants and even U.S. citizens.

What I see as critical is the issue of how long, and when is the officer going to exercise discretion to release the person, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the first Hispanic on the bench, told Paul Clement, Arizona's lawyer.

Learning that there is no federal citizens database to check if someone is authorized to be in the country, Sotomayor voiced concern for U.S. citizens who are detained while law enforcement awaits an answer from the federal government. She used a scenario of a citizen who ran out of the house without a driver's license or proper documentation and was later arrested.

You're arrested. They make the call to this [federal] agency. You could sit there forever while they figure out if you're a citizen, she said.

Clement was unable to guarantee that a U.S. citizen from New Mexico detained in Arizona for being a suspected undocumented immigrant -- a hypothetical offered by Justice Stephen Breyer -- would not be in detention any longer than normal under the challenged law.

Clement, pointing out the statute, which is under a stay from a lower court and has not yet gone into effect, could assure Breyer only that the hypothetical person would be detained within the Fourth Amendment, which bans unreasonable seizure.

There will be a significant number of people who will be detained at the [traffic] stop, or in prison, for a significantly longer period of time than in the absence of the statute concerning police power, Breyer said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.