Worried About Undercount, States And Cities Spend To Promote 2020 Census

By law, the United States government is responsible for conducting a census every 10 years to count all of the country's residents. But in the lead-up to the 2020 census, state and local leaders have made it clear they will not rely on the federal government to ensure an accurate count.

State governments, foundations and local governments are committing hundreds of millions of dollars to convince people to fill out their census forms, in what is likely to be the most expensive grassroots census campaign ever.

The stakes are high: Population data collected in the census not only serves to allocate congressional seats; it also determines how the federal government divides an estimated $800 billion each year for such things as public housing, highway construction, Head Start, Medicaid and Medicare. An undercount could cost states billions of dollars in federal revenue.

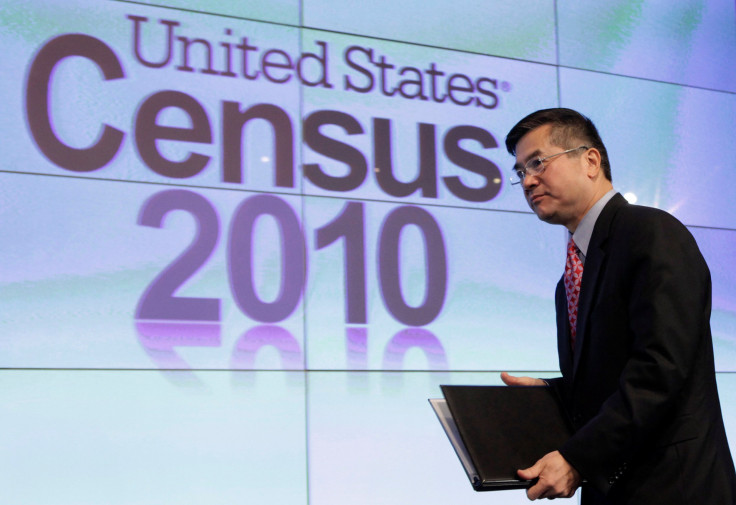

Some of the groups most likely to receive federal aid are also among those most often missed by the census. The Census Bureau's own analysis found that it undercounted young children by 4.6 percent in the 2010 census and missed 1.1 percent of renters (a category sometimes used as a proxy for low-income residents). Homeowners were over-enumerated by more than half-a-percent.

States with large immigrant populations are particularly worried for 2020. They say they have seen widespread distrust of government among immigrants because of heightened immigration enforcement. And for the first time in 70 years, the Census Bureau intends to ask all people whether they are U.S. citizens, a question many worry will further suppress immigrant participation. More than two dozen states and cities are suing to get the question removed.

California has said it will spend $100 million on outreach, dwarfing the $2 million it spent on the 2010 census, when the state had a severe budget crisis, and the $25 million it spent in 2000. Salt Lake City has budgeted $80,000 to hire its first-ever census director. New York City has allocated $4.3 million, the first time it has formally budgeted for census outreach.

In addition to state and local governments, some 74 grant-makers nationwide have committed $30 million to census efforts.

Even so, government and nonprofit leaders across the country expressed doubt in interviews that money alone will be enough to coax wary populations to raise their hands.

“Certain communities,” said New York City Deputy Mayor J. Phillip Thompson, “may just be too frightened to participate.”

'IT'S A TRICK'

The National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials has been running focus groups to identify effective ways of maximizing census participation. The group's chief executive, Arturo Vargas, said the citizenship question raised alarm bells in focus groups conducted with immigrants, and that participants said they had little confidence their data would be kept private.

They also worried about completing census forms online, another innovation of this year's census. “My mom is 61 years old and she’s not going to go on the computer,” said one focus group respondent. “She’ll think it’s a trick.”

NALEO’s research found that immigrants responded positively to messaging that cited their legal obligation to complete the census. Younger Latino men responded well to ads portraying the census as a way to defend their communities.

Traditional messaging emphasizing civic responsibility “ain’t gonna work,” said Allan Oliver, of the Santa Fe, N.M.-based Thornburg Foundation.

Many state and local officials expressed concern that the citizenship question in particular would depress participation. “Citizenship might be relevant to the federal government, but for those of us who run local governments, we have to treat the sewage,” said Westchester County Executive George Latimer, whose county has appointed an advisory board to help boost participation. “I don’t know if it’s generated by a citizen or not.”

Los Angeles Census Director Maria de la Luz Garcia said the city's efforts have focused on practical concerns, including planning for computers at local libraries to perform double duty as kiosks for filling out census forms and preparing to include census reminders in city utility bills.

The bureau has said it can conduct the 2020 census more cheaply because, with online responses, it will be able to hire fewer enumerators than in 2010 and open fewer field offices.

But some local government officials say their constituents will need human contact and encouragement in this census more than ever.

Every person not counted will ultimately cost his or her state $19,500 over the next decade, a study by George Washington University’s Andrew Reamer estimated. California, for example, lost out on at least $1.5 billion of aid due to uncounted residents after the 2000 census, a PricewaterhouseCoopers study found.

FUNDERS CIRCLE

Philanthropic groups in 21 states so far have formed state-level census outreach efforts, in many cases for the first time.

In rural New Mexico, where getting an accurate count has always been difficult, a group led by the Thornburg Foundation and the Albuquerque Community Foundation are aiming to raise $600,000. In Minnesota, which has the nation's largest Somali population, foundations have designed a $4.8 million campaign, asking Minnesota’s government to chip in $1.25 million.

The foundation-led New York Counts 2020 coalition plans to raise $3 million, and is urging the state's government to pony up much more, citing California's example.

Ditas Katague, who oversees census outreach for California, said that even with the state's $100 million campaign, the task is difficult.

“We’re way ahead of where we were in 2000 and 2010,” Katague said. “But the feeling is that we’re behind.”

Reuters

(Editing by Damon Darlin and Sue Horton)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters {{Year}}. All rights reserved.