Ahead Of Democratic Primary, Black Michigan Voters Want Solutions From Clinton And Sanders, Not Economic Rhetoric

The lead-up to Michigan’s primary election Tuesday has shown just how intent Democratic presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton are on securing the state’s black vote. Before the Vermont senator and former secretary of state, respectively, canvassed Michigan this week, a heated, revealing debate Sunday night in the city of Flint highlighted their varying levels of comfort in talking directly about issues that affect black communities.

During the debate, Sanders forcefully condemned Clinton for her previous support of trade deals that he said sent American jobs overseas, a critique he has made frequently while campaigning in Rust Belt states hurting from manufacturing declines. But ironically that’s not the message black voters in Michigan — many of whom are struggling with unemployment — want to hear, some African-American groups there said in interviews this week. Instead, they're more focused on how candidates’ solutions can address problems they currently see at home than on rhetoric about national issues like free trade.

“There is a space for conversation around trade agreements, and we saw that with the [Trans-Pacific Partnership], but when we’re talking about jobs and access, a lot of folks are talking about basic public transportation to get to those jobs,” said Denzel McCampbell, a 24-year-old activist in Detroit with Black Youth Project 100 (BYP 100), which says it's focused on “creating justice and freedom” for all black people. “A lot of folks are talking about not having access to water and Flint having poisoned water, having struggles with foreclosed homes and just trying to get by day to day.”

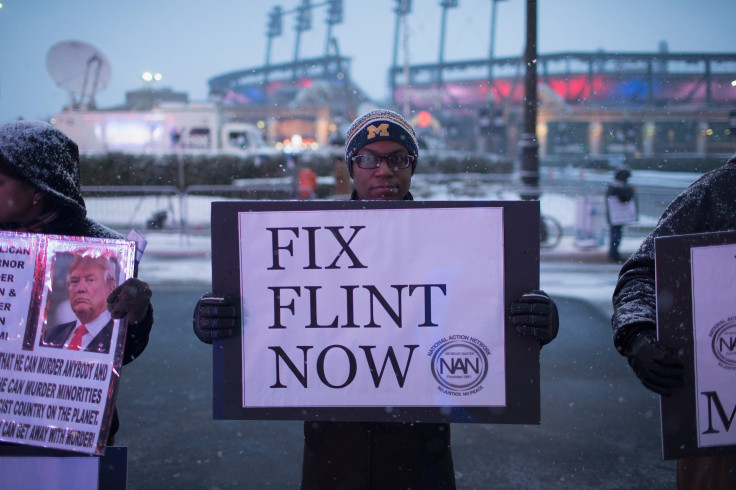

Michigan is known as a heavily industrial state, but over the years many corporations have moved jobs from cities like Detroit to other countries where wages are cheaper. This has contributed to a high rate of unemployment in the state, particularly among African-Americans, and a water crisis in Flint caused by lead pipes contaminating the city's water has added to many residents’ feeling that the government has abandoned them.

McCampbell said he watched the Democratic debate Sunday night and liked Sanders’ economic and healthcare policies, but he emphasized that people he knows are looking for a “well-rounded” approach to helping African-Americans. His friend Kevin Rigby Jr., who is co-chairman of the BYP 100 chapter in Detroit, agreed, adding that neither Democratic candidate demonstrated an understanding of the issues most affecting black people's lives.

“Something that’s lost on these candidates is the intersectionality of helping black communities,” Rigby said. “Bringing back jobs is good, but it’s very hard to take advantage of that if you’re caught up in the prison system. You also need investment in education and transportation. An agenda that seeks to remedy black futures has to take into account those things because it’s not enough to have a job if you can’t get there, if you’re constantly getting stopped by police or caught up in the judicial system.”

Both Democratic candidates have developed plans to address criminal justice reform and have tried to use Flint as an example to talk about how they would help similar black communities around the country. While Clinton has made the crisis a main talking point on the campaign trail over the past few weeks, Sanders delivered a strong performance Sunday night, giving clear answers on issues such as fracking and accountability for Flint, while Clinton sometimes seemed to meander. Still, she led by double digits in Michigan ahead of Tuesday, and the latest Fox 2 Detroit/Mitchell poll had her leading Sanders 79 percent to 11 percent among black voters.

African-Americans make up about 14 percent of Michigan’s population, but because they are mostly Democrats and tend to be reliable voters, political analysts have predicted that they could account for 20-30 percent of Tuesday’s primary electorate. To try to win over African-Americans, the Sanders campaign spent a good deal of time talking to voters and the media about Clinton’s support for the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta), which her husband signed into law when he was in the White House. Though Nafta reduced trade tariffs among the U.S., Canada and Mexico, and likely did cause some jobs to move outside the United States, fact checkers have questioned Sanders’ claims about how much trade policies like this have directly contributed to the decline of Detroit and other cities.

Clinton has fought back against her opponent by saying she now opposes President Barack Obama’s Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal, just like Sanders, and by frequently talking about the need to help the middle class find jobs and raise wages.

The people of Detroit know the real cost of Hillary Clinton's free trade policies. pic.twitter.com/OoatUvhEc9

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) March 3, 2016

Still, for Michigan residents living in poverty or for those who are still brushing their teeth with bottled water to avoid lead poisoning, the theory of how candidates want to get them their jobs back is not always their highest priority.

“There’s kind of two sentiments that exist at the same time, and they can seem conflicting," said Laura MacIntyre, a professor of sociology at University of Michigan–Flint. "One is, we’re done, we’re completely fed up with government. There’s a sense that we’ve been lied to. But on the other hand, there’s a real sentiment of: Get out the vote. We have to fight this at the ballot box even though we’ve been fighting this at the ballot box and have been ignored.”

MacIntyre, who is white, was born and raised in Flint, and said many of her friends there are worried the national attention will go away once they vote Tuesday, leaving the community without leverage before a resolution is found. With this in mind, trust is an important factor in many black voters’ decisions, Michigan residents said.

“Seeing the history of Mrs. Clinton and her husband, I don’t have too much trust in her policies. We know the politicians come in and promise things and leave,” said Leon El-Alamin, CEO and founder of the M.A.D.E. Institute, an organization in Flint that helps previously incarcerated individuals integrate back into society. “From a personal standpoint and a community standpoint, I’m leaning more toward Mr. Sanders. I think we need someone who’s fresh and new.”

It's not enough to talk only about economics. We have to tackle racial, economic, & environmental justice—together. pic.twitter.com/AXTyWE6x4W

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) March 7, 2016

After losing to Clinton by wide margins in South Carolina and other Southern primary states, Sanders said he hoped to do better among African-Americans outside the South. But political analysts have said voting patterns among blacks in different regions are not typically different enough to deliver a win for the Vermont senator.

“Fairly or unfairly there's a sense that Sanders is coming to the party late. Whatever efforts he makes, however sincere they are or however sincere they appear to be, he is not going to be perceived as having been in the fight over the long term,” said Vincent Hutchings, a political science professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Rigby, the activist from Detroit, who plans to vote for Sanders on Tuesday, echoed this idea, saying the senator had not yet succeeded in communicating his vision to African-Americans in the state.

“I don’t know that folks understand what those plans for bringing jobs back look like, and that’s an increasingly important question in a rapidly deindustrializing state like Michigan,” Rigby said. “Folks don’t know who he is, they don’t understand what he’s saying to them. It’s not their inability to understand the policies. It’s on him and his inability to communicate.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.