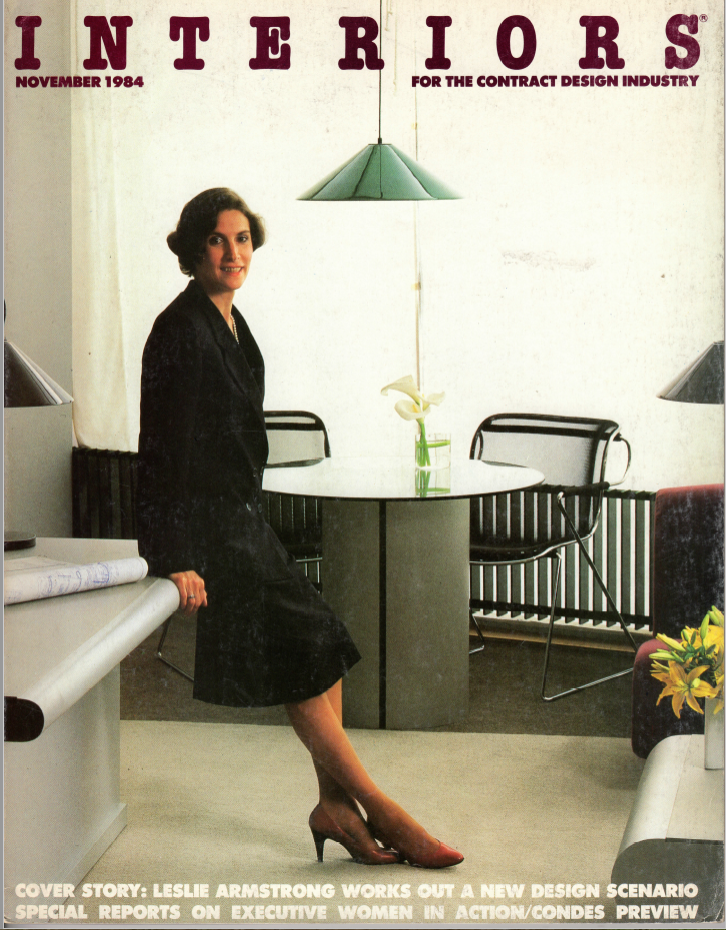

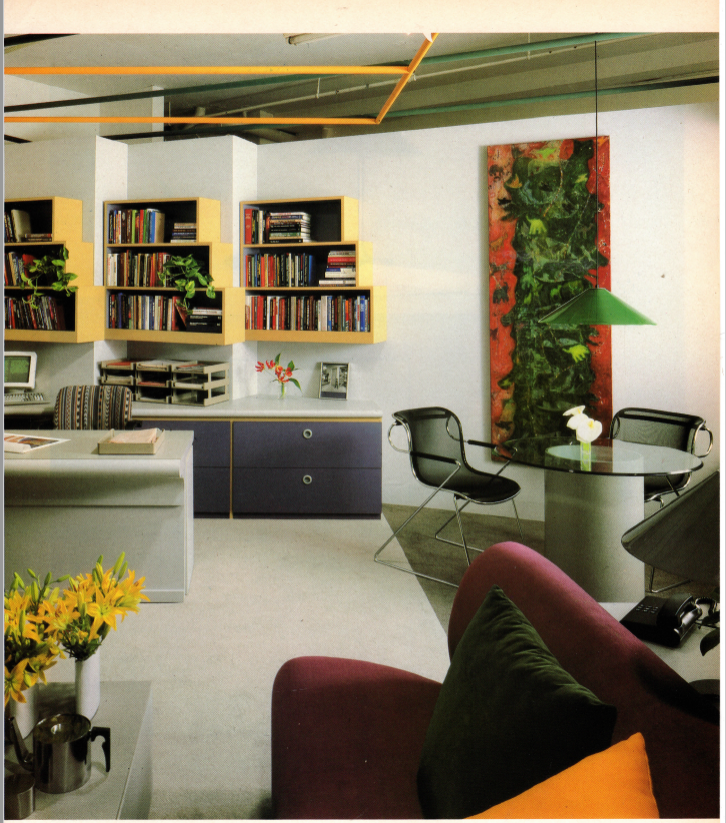

An Architect Comes of Age in 1960s New York

Architect and author Leslie "Lale" Armstrong AIA has been a professional for more than 50 years, opening her first firm in the early 1970s. This excerpt from her memoir Girl Intrepid: A New York Story of Privilege and Perseverance (to be published by Epigraph Books on Oct. 1) describes experiences of the kind that beset many entrepreneurial young women--if they ventured into a man's profession in mid-20th century New York City.

I started my first paid architectural job working for Warner Burns Toan & Lunde, a New York firm concentrating on institutional and hotel design. I was put to work on the schematic design for a new building for Hofstra University. I wasn't drawing or designing so much as researching--analyzing and diagramming the program elements of this complex building so that when the actual designer began to work, he or she would get the functions right. I loved being in a real office, working with people of all ages and levels of ability. I loved coffee breaks and lunch breaks. Most of all, I loved the work.

Rocket Science

During the spring of 1968, I pressed on, though I was expecting our first child. We were consultants to Grumman Aircraft, which was preparing its submission to NASA for the design and manufacture of the United States' first manned orbital space station. Grumman had been awarded the contract for the design and construction of the Lunar Explorer Module (LEM) that eventually went to the moon in June 1969, manned by Neil Armstrong (no relation) and Buzz Aldren, and Grumman thought it had a real shot at the space station.

Our job involved planning the deployment of various living, maintenance, and experimental work functions, which were to be housed within an eighth-inch-thick aluminum cylinder that was the core of the station. Our drawings were always vertical, showing the cylinder upright atop the rocket, as it would be on the launching pad where it would be assembled. But eventually my belly got so big that I had to lay both the rocket and the habitation/work cylinder on its side in order to get at everything on the drawing.

I was near the end of my second trimester when we began our weekly meetings out at Grumman in Long Island. At Grumman, pregnant women were let go after their first trimester. Not only was I regarded as a kind of freak, but I had to pee at least twice as often as the other meeting attendees. Because the Warner Burns team had no security clearance, and there were so few women at Grumman and thus even fewer ladies' rooms, whenever nature beckoned, the meeting had to be stopped and I'd be escorted for miles through the adjacent airplane hangar where the LEM was being assembled--by hundreds of little people scurrying around in white jump suits, gloves,hoods; very James Bond--to the one ladies' room. My escort would wait for me outside, and then back we'd trek.

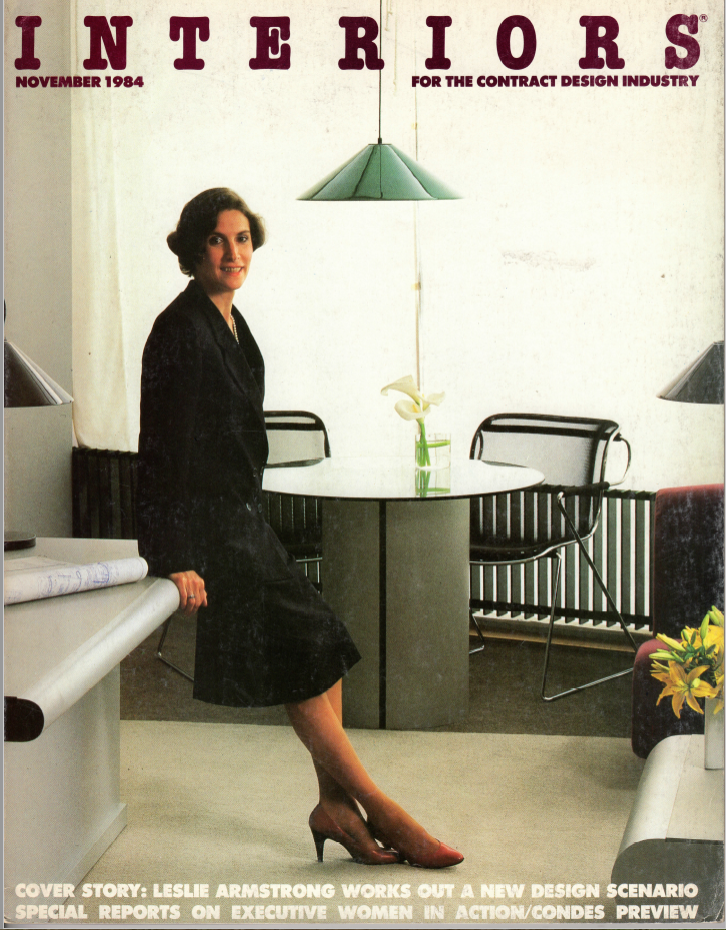

A Theatrical Experience

A little while after Vanessa was born, I threw myself into my latest job, which was to design a new home for the American Place Theatre, underneath a plaza behind a new office tower to be built on Sixth Avenue between 48th and 49th Streets. My new employer, Richard D. Kaplan, had a father, a well-known philanthropist, who had set him up in business and was steering public housing projects his way. Because Richard's office was nicely subsidized, he could afford to do it well.

When I was well into the project, Francisco, our job captain, quit because he thought our boss was immoral and inept. Kaplan didn't have the balls to allow me to run the job (and maybe he was right, as I was only two years out of school) and instead hired Frank, a macho scumbag whom we had met previously when he hand-delivered hard drugs to the office.

Frank wore open shirts, jeans, and cowboy boots to work at a time when that wasn't done,and he had three-martini lunches with other guys in the office every day. He allegedly had a degree in architecture but he knew nothing about theatre or design. However, as my superior, he refused to allow me to attend project meetings with the client for fear of his being shown up. Kaplan supported him.

I was distraught, but this was my first big design job. I couldn't quit. I knew Kaplan was dependent on me to finish working out all the detailed aspects of the design. I contained my frustration and continued to work hard, despite the insult of Frank having authority over me.

Coming From Money

When we were near the end, Richard invited me into his office after everyone had gone home, closed the door and had me sit down. "You are good at detail and good at money, Lale," he said. "You understand what it is to come from money."

Was my background so transparent? I thought. Maybe it was the Gucci shoes. Maybe I shouldn't wear pearls to work, even if they were fake.

"I need someone with your experience and understanding to run my personal life, to serve as my personal secretary," he continued. "You would be terrific, and it would be a great job for you."

"What about architecture?" I stammered in disbelief.

"It's too tough. You'll never make it. Look what happened with Frank."

"LOOK WHAT HAPPENED WITH FRANK?" I wanted to shout. "You made what happened with Frank happen!" But I was tongue-tied. Finally, I muttered that I would think about it. I returned to my desk, got my purse and my coat, and took to the fire stairs down to the lobby rather than stay in the office long enough to await the elevator.

Descending the twelve flights of stairs to the street I felt as though I had been violated. On my way to the subway, I decided that I would have to find someone who would suit Kaplan's needs as a personal secretary so I could stay on, complete the design and, more important, get credit as designer of the theatre. I asked around and learned of a well-heeled young woman from Laurel, Mississippi, Cynthia Chisholm. Her family had supported and largely subsidized Leontyne Price. Cynthia would understand what it was to come from money. I called her, introduced myself and told her about the job. Soon afterward, she was hired.

Eventually, almost all of Richard Kaplan's staff quit except my nemesis, Frank. He was kept on to manage the construction of the American Place Theatre, the only job Kaplan's short-lived firm ever got built. Cynthia Chisholm stayed on to manage Richard. When the theatre was completed and opened, The New York Times published an article about the amazing new theatre forty-five feet below the streets of New York. Credit was given to Richard D. Kaplan, architect. Frank was named as designer.

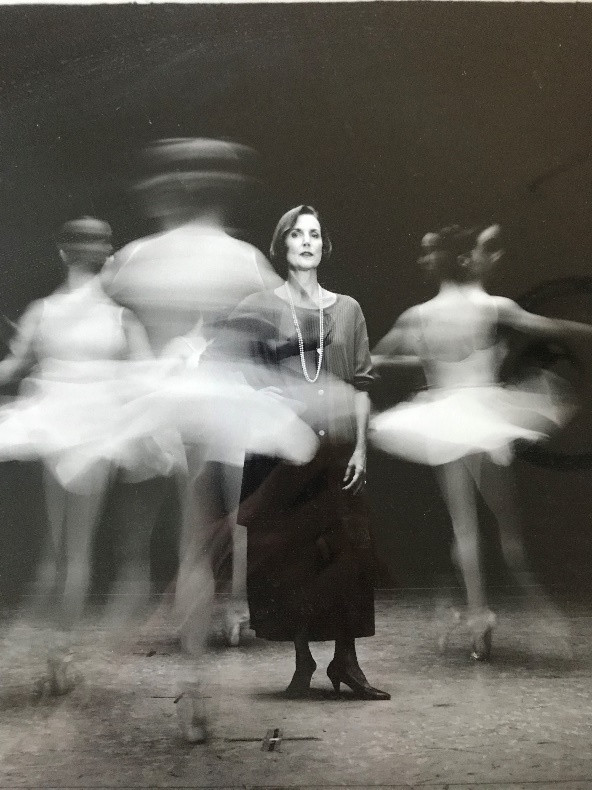

A Firm Of One's Own

A friend had introduced my husband Louie and me to her childhood friend, Russell Childs, also an architect, and his new Scottish bride, Kirsten, an interior designer from Inverness. Russell had just finished Artpark in Buffalo for Vollmer Associates. Kirsten was finishing the interiors of a big house in Long Island for Richard Meier.

A year later Russell announced their plan to go out on their own. They had taken office space downtown opposite the Flatiron Building for $300 a month; did I want to come in with them?

In early 1973, Armstrong Childs Associates, which Kirsten nicknamed "Archie," was born. We set up shop in two rooms at the rear of the fifth floor at 174 Fifth Avenue--then a very dirty and depressed neighborhood. We shared a receptionist's desk, conference room, and resources library with two other small architecture firms.

My new partners were at the forefront of the movement towards sustainable and environmentally responsible design, and brought several projects with them; new offices for the Natural Resources Defense Council, and a house in Reading, Connecticut for friends. I brought in The Parents' new apartment, a renovation/restoration of a large Italianate villa in Fairfield, Connecticut, for a friend of Louie's, and the possibility of redoing The Parents' brownstone on 62nd Street for its new owners, James Taylor and Carly Simon. We were off and running.

Russell was an experienced designer and an excellent draftsman and illustrator. He was our team leader, the cock in our roost. He occupied the larger office together with our small staff. Kirsten and I were the workhorses. We designed and documented all the interior work. In the small office that we shared, I started to grow into the designer I am.

Most of our projects were renovations rather than new construction. Along with our occasional office designs, we joined with James R. Grieves of Baltimore to renovate and restore the nineteenth-century Grand Opera House in Wilmington, Delaware. On our own, we remodeled John Johanssen's controversial Mechanic Theatre in Baltimore and renovated five disparate buildings of various vintages for the theatre and music departments at Brown University. And, of course, we did myriad residential projects for friends, friends of friends, and family members.

Professional Life Lessons

Kirsten and I were joined at the hip with respect to what we wanted from our lives, our friends, and our work. We both believed that women deserve the same opportunities and compensation as men, but we preferred the reward of work and good times to that of political action.

I had a one-semester gig as an adjunct at Columbia, teaching second-year design studio. When we adjuncts were asked to give presentations of our work to the students, I entitled mine "Kitchens, Closets, and the Performing Arts." I wanted the students to know that entry-level architects with their own businesses don't start designing skyscrapers or trendsetting houses. We take whatever walks in the door, work our asses off, and are proud when our projects improve the environment and the lives of the people who inhabit them.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.