Despite Toyota Patent, Flying Cars, Though Technically Possible, Have A Long Way To Go Before They're Ready For The Masses

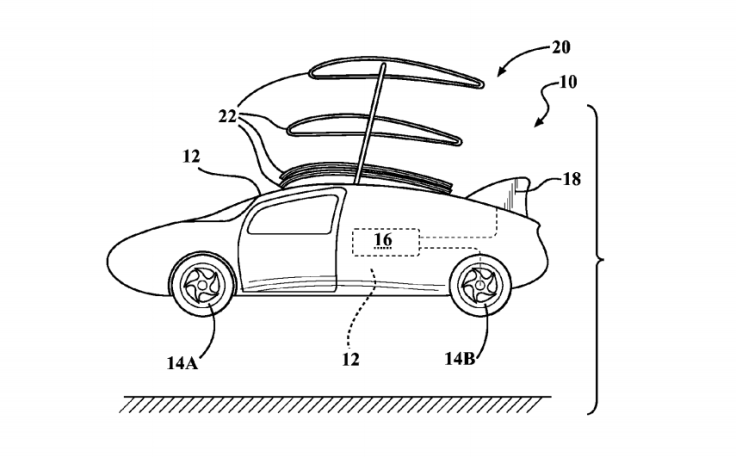

Toyota’s recent “Aerocar” patent has thrust the subject of flying cars into the spotlight. The Japanese automaker’s so called stackable wing seems to resolve one of the major challenges of flying-car design. Instead of wings stretching out from the sides of the vehicle, making it too wide for conventional roads, Toyota envisions a stack of multiple wings on top of the vehicle to provide the necessary aerodynamic lift.

That the patent was filed by the world’s top automaker offers considerable legitimacy to the idea of a sky filled with high-flying commuters. But before you start making references to the flying taxis and police spinners of Hollywood fame, keep in mind that even existing prototypes shopped around by a small number of startups look more like hobbyist aircraft for people who can afford $300,000 toys. We’re nowhere near the days of mass-producing flying Toyota Camrys.

“It’s incredibly inefficient,” John Brown, a project manager at Carplane, a German company working on its own flying car, told the Washington Post about Toyota’s stackable wing design. “And it may actually be too inefficient. You’d have to put it in a wind tunnel and see just how efficient it is.”

Toyota has pointed out it’s not working on full-fledged flying cars, but rather something akin to hovercraft. Speaking at a technology event in San Francisco last summer, Toyota official Hiroyoshi Yoshiki said his company is exploring how to get cars "a little bit away" from the road to reduce friction. No known prototype of the Toyota’s design exists and like many patents, the stackable wing design may never be built.

The idea of merging motor cars with airplanes has been around since the days of 19th century sci-fi writer Jules Verne, whose land-air-sea vehicle, the “Terror,” was the subject of his short story “Master of the World,” published in 1904. While the technology exists to build vehicles that can drive and fly, bigger challenges persist.

For one thing, unlike autonomous driving vehicles, flying cars would require considerable changes to infrastructure. Like airplanes, flying cars as they’re being designed would need ample runway space for taking off and landing.

“Such a system would only succeed if infrastructure – air traffic control, landing space and so on – was set aside,” wrote John Preston and Ben Waterson of the University of Southampton’s Transportation Research Group in the Guardian late last year. “While flying cars could technically operate from airport to airport, what’s the point? Until there are sufficient numbers to set aside pieces of land or roads for takeoff we won’t achieve any of the benefits.”

Other problems include more practical matters, such vehicle safety standards. Aircraft are by nature designed to be light while vehicles require considerable structural integrity to meet basic crash-safety standards. How to build an aircraft that would meet both requirements would be a design challenge.

Bowing to pressure from flying car startups like Terrafugia, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration in 2012 created a new classification to accommodate the vehicles, known as light-sport.

“The FAA coordinated with the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration for the Terrafugia to determine the clear responsibility between the requirements for road operations and air operations,” the FAA said in a statement to the New York Times in 2012.

The light-sport classification allows developers to build aircraft that are road ready, but that don’t require the more stringent safety requirements of a typical car. For example, the road-ready light-sport aircraft can use motorcycle wheels and tires, and polycarbonate plastic windows instead of automotive glass that can shatter in bird strikes. Pilots can acquire licenses to drive the vehicle with just 20 hours of instruction, about a third of what required for a U.S. private pilot’s license.

But nothing we’ve seen from the small number of startups would indicate a mass embrace of flying cars. For one thing, the price is prohibitive. Terrafugia says its flying car would start at $300,000. Flying cars from rivals AeroMobil, Moller International and PAL-V will cost about the same. So even if the infrastructure existed to accommodate a mass embrace of flying-car technology, the costs will keep it from filling the skies.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.